Daniel Quiroz spent a recent Saturday morning mowing the yard of his uninhabitable house.

The short-cropped blades of grass resemble artificial turf. A neatly trimmed tree stands sentinel in the front yard. And a blue baby swing hangs from a sturdy branch. It looks lived in, even if that’s not the case.

“It’s kind of like, ‘Hey, there’s a family that lives here. Don’t mess with this house,’” Mr. Quiroz says.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

Wildfire turned vibrant Altadena to rubble. The Monitor is following what comes next on one block: how neighbors rebuild, how communities change, and how resilience appears in the aftermath of disaster. This is the second installment in a series; Part 1 is here.

More than five months ago, the Eaton wildfire blazed through this Greater Los Angeles community of Altadena. Home after home – and generations of keepsakes – burned. Mr. Quiroz’s tidy white house with black accents survived.

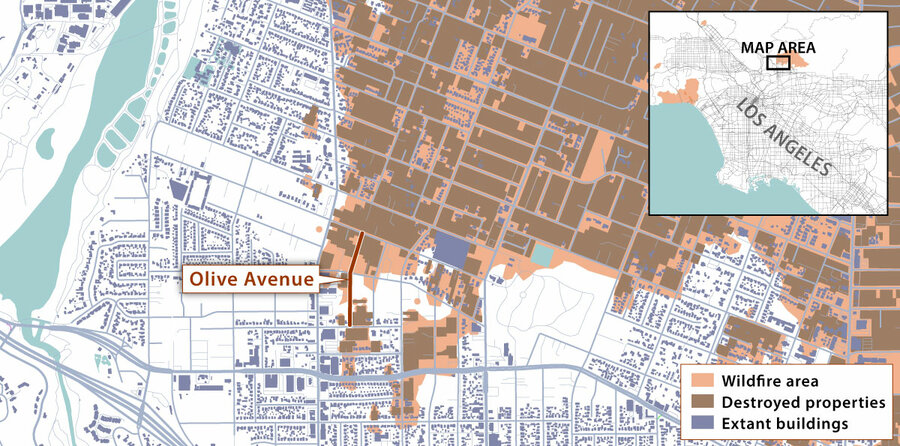

But his family still can’t live in this 777-square-foot stucco-sided bungalow on Olive Avenue – at least not yet. Damage from the fire, along with related environmental concerns, has made it unlivable.

Mr. Quiroz, a sanitation worker for the city of Los Angeles, and his partner, Joann Flores, an escrow officer, say they are blessed. Their family? Safe. Their house? Still standing.

But on the mountain-facing side of the house, an air conditioning unit, electrical panel, and wall of pine trees caught fire during the blaze. A window melted. Inside the backyard garage, his yellow 1998 Honda Civic EK2 burned. On a nearby street, the fire reduced his childhood home, where his mother and sister lived, to rubble.

His mother’s house was one of more than 9,400 structures destroyed by the Eaton wildfire in Altadena alone. Further west, near the Pacific coastline, the Palisades blaze leveled more than 6,800 structures, both houses and businesses, that same January week. About 2,000 other buildings were damaged.

Nearly half a year since the infernos swept through their neighborhoods, thousands of people remain displaced – those like Mr. Quiroz’s mother, who lost homes, and those like Mr. Quiroz and his family, whose homes still stand. On Olive Avenue, residents are asking the same questions as many of their fellow Los Angelenos – and the same questions as a growing number of Americans who have been uprooted by extreme weather events, from tornadoes to hurricanes, floods to wildfires.

Should they return and rebuild? Can they afford it? Or is it better to move elsewhere, farther away from disaster risk? And what good might rise from the literal ashes of their former lives?

Often, the spotlight on communities impacted by disaster starts and ends in the moment of trauma. The Monitor decided to take a longer-term view, following families in the Olive Avenue neighborhood as they grieve, laugh, move, rebuild, and navigate what comes next. Five months after the fires, debris removal is forging ahead, displaced residents have settled into new routines, and time and money concerns are mounting.

Who handles disaster recovery – and how – is a point of national debate. President Donald Trump has indicated states should carry more of the burden, relieving the backlogged Federal Emergency Management Agency. Critics, however, say that would hamper recovery efforts.

Nearly two-thirds, or 64%, of Americans support the idea of governments providing financial assistance for people to rebuild following extreme weather events, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey. An even greater share, 77%, want stricter building standards for new construction. And roughly half say the government should not require people to move out of high-risk areas.

But survivors’ guilt creeps in as Mr. Quiroz and Ms. Flores care for the house they hope to return to later this summer. For now, they are living with their 17-month-old daughter, Darla, in a nearby apartment.

“When I am cutting my grass, I have my head down,” Mr. Quiroz says, describing his tendency to avoid neighbors while doing yardwork.

A patchwork of progress

At this point, Altadena is a patchwork of progress. In a quiltlike pattern, fire-ravaged lots sit next to burned home sites that have been cleared. The latter are multiplying rapidly, though.

As of late May, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reported that ash and debris had been removed from more than 5,000 properties within the burn zones of the Eaton and Palisades wildfires. In the Eaton burn area, specifically, about 62% of properties had been cleared and had received “final sign off.” That means trees deemed hazardous have been hauled away, too, and erosion control has been applied to the lot.

One of those cleared lots sits across the street from Mr. Quiroz and Ms. Flores’ house on Olive Avenue. It’s where their neighbors, Lorna Green and Nicole Moore, lived with their teenage daughter, Umalali. In February, they were still digging through the contents of their burned property when the Monitor first visited.

Construction crews had arrived a few weeks earlier to remove ash and debris from their lot. The couple asked Mr. Quiroz if they could park in his driveway while they watched. He agreed without hesitation.

If homeowners wish to rebuild after debris removal, they must secure permits from the county. But underlying that process, Ms. Green and Ms. Moore say, are many financial questions. What kind of architectural plan do they want? What will the price per square foot be? Will tariffs skyrocket building costs?

“We haven’t even remodeled a kitchen,” Ms. Moore says with a laugh.

And then there are environmental concerns. The Army Corps announced in February that it won’t perform additional soil testing after removing 6 inches of topsoil from fire-razed properties. The decision immediately received pushback from residents and politicians alike who worry about the hazardous toxins that may still be lurking within the soil. The uncertainties cause Ms. Flores’ mind to wander when she thinks about her daughter.

“Can I take her outside to play?” she wonders.

A neighborhood park rises again

Excavators rumble and dump trucks roar, even on weekends. But on this Saturday afternoon in May, another sound drifts through the fire-ravaged community. It’s music coming from a park celebrating its grand reopening.

Loma Alta Park sits on a 17-acre parcel just below the San Gabriel Mountains. It was a communal epicenter of western Altadena, bringing people together for baseball games, swimming, equestrian trails, an indoor gymnasium, and outdoor play. Then the wildfire blanketed the park in ash, burned playgrounds and a storage unit, and caused other cosmetic damage.

Today, despite drizzling rain, the towering jungle gym in the park bursts with children and laughter.

Nine-year-old Cecily Wallinger beams as she instructs her parents to stand at the bottom of the slide. She glides down, happily bouncing out before bounding back up the stairs. The playground equipment is new.

She grew up coming here with her parents, Bridgette Campbell and Christopher Wallinger. It’s a short walk from where their house once stood near Olive Avenue and Harriet Street.

“I do actually have photos of the whole house,” Ms. Campbell says, before grabbing her phone to marvel at the part she misses most: a garden. “We literally did it on our hands and knees,” she says. “So we were very, very proud of it.”

Snippets of conversations just like this – of life before and after the fire – could be heard throughout the park. Its grand reopening brought together old neighbors and friends, many of whom are at least temporarily living outside Altadena.

Now, the cleaned-up park gives subtle nods to the city’s current reality. Colored Adirondack chairs, labeled with “Alta Chat” signage, serve as outdoor living rooms. In one such cluster, the conversation is about insurance hurdles.

Earlier in the morning, protesters also showed up here. They toted signs with messages such as “DIRECT CASH ASSISTANCE FOR STRUGGLING FIRE SURVIVORS.”

On the playground, Ms. Campbell ponders the Altadena of tomorrow. Maybe it will boast more businesses, she says, and certainly houses that look different. She and her husband moved to Altadena from West Hollywood when their daughter was 18 months old.

For the time being, they are living in a Pasadena apartment after the blaze wiped out their home. The complex has a pool for their daughter. Eventually, they want home to be here again.

“Deep in our bones, we don’t want to live anywhere else,” she says.

A ticking clock

Mr. Quiroz and Ms. Flores have a ticking clock – a lease that runs out at the end of July.

That’s when they hope to move back into their house on Olive Avenue. The money the couple received from insurance for temporary living expenses is dwindling.

A hygienist company recently determined their house needs professional cleaning, Ms. Flores says, but does not contain harmful levels of asbestos and lead. The good news jumpstarted the rest of their to-do list. Top priority was returning power to the house. That would restore one piece of normalcy – being able to use their own washer and dryer. Laundromats and professional cleaning services are among their recent Yelp searches.

All told, the couple expect to shell out roughly $25,000 of their own money before moving back to Olive Avenue. That figure includes a new roof, air conditioning system, and furniture. They worry about toxins that may have seeped into the plushy fabric of couches and mattresses.

Safety weighs heavily on them as new parents. But this is where they want Darla to grow up, even if it takes longer for the surrounding neighborhood to repopulate.

“I think we’ll be happy,” Mr. Quiroz says.

His partner finishes the thought.

“We kind of don’t have a choice,” Ms. Flores says. “We have a mortgage.”