This article is taken from the July 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

As the critic Edwin Evans observed in The Sketch in January 1940, war forced many people to reflect on the importance of the arts. “The majority of Englishmen,” he wrote, “class music, and for that matter, the arts generally, with ‘luxury trades’. It took a month’s deprivation to make them realise what life might become if it had no music.”

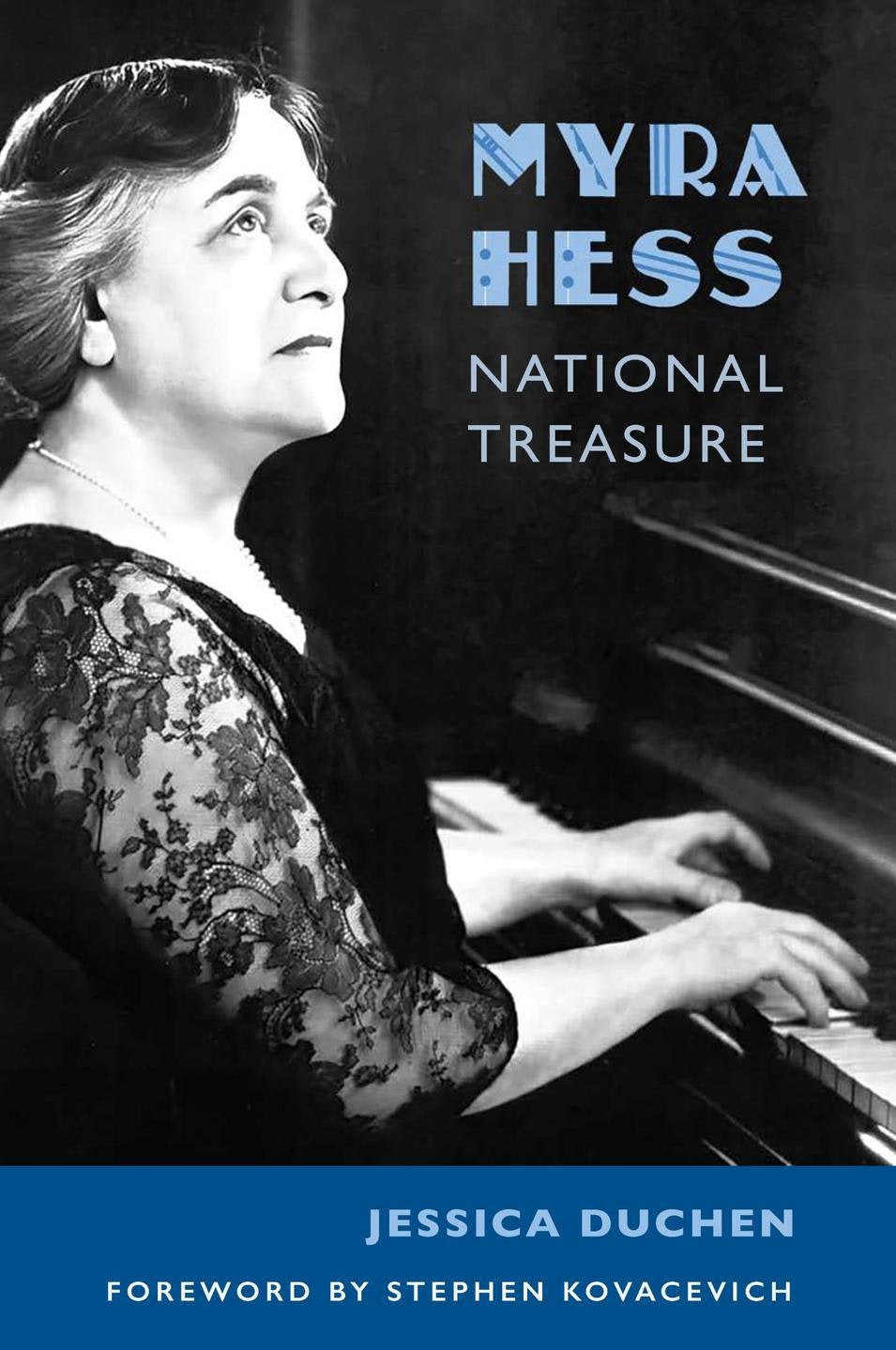

A key figure in keeping music alive was the pianist Myra Hess, who organised a series of concerts at the then empty National Gallery, its paintings dispatched to the countryside for safekeeping.

Jessica Duchen’s chunky, sumptuously illustrated biography of Hess draws upon a vast number of primary sources to document her life, performing schedules and repertoire in painstaking detail.

Writing about artistic figures can be challenging, since so much of their time is devoted to the repetitive business of perfecting their craft. However, Hess’s story is greatly enlivened by Duchen’s vivid account of her travels: on queasily pitching transatlantic liners, trains across the Balkans and an aeroplane whose engine dropped off just weeks later. As Hess remarked, “there are not more female pianists because most women are too sensible to wish to spend their lives on trains.”

Hess’s life is also fascinating for her dizzyingly large network of friends, mentors, colleagues, students, agents and acquaintances, making this book far more than a single life story. Duchen is on cosy first-name terms with most of these figures — Hess herself is “Myra” throughout — which gives the biography an intimacy reminiscent of Leah Broad’s Quartet, a recent study that shares with Duchen’s a certain affinity in subject matter and tone.

The fact that important male musicians — Bax, Rachmaninoff, Casals, Toscanini — are referred to by surname, however, gives pause for thought.

As a young woman in the 1910s, Hess was part of a vibrant, cosmopolitan North London circle of aspiring artists, for whom it was the norm to dabble in spiritualism, travel to Germany for music lessons or hop over to the Netherlands for a concert. Groups of single women could even club together to rent a stucco-fronted villa in St John’s Wood, though here all was not idyllic. Hess had to endure the suicide of two of her housemates (sisters of the novelist Ivy Compton-Burnett) after the death of their beloved brother at the Somme.

At times Hess’s personality seems slightly overshadowed by those of the more colourful members of her social set, a feeling intensified by her apparent lack of any real love life. Duchen hunts hard and draws a blank, though she speculates Hess may have held a torch for Arnold Bax, a married man who was already entangled with the pianist Harriet Cohen.

Perhaps it was to Hess’s advantage that any would-be romance never came to much: when Bax’s wife died, he failed to tell Cohen, his mistress of 30 years, nor did he reveal that he had had another mistress for the last 20 of them.

Audiences picked their way undaunted through broken glass and rubble

The most interesting part of the book is, perhaps unsurprisingly, devoted to the war years. Inspired by friends who asked her to play to raise their spirits, Hess pitched the National Gallery series to Sir Kenneth Clark, whom she had never previously met. This being an era before the arrival of red tape and health and safety, he simply said yes and urged her to arrange concerts daily. They were a magnificent undertaking, continuing throughout the Blitz, with audiences picking their way undaunted through broken glass and rubble.

German music was regularly programmed. Whilst in 2022 Ukraine’s culture minister called on allies to boycott Tchaikovsky, Hess’s audience, in Duchen’s words, “was perfectly able to distinguish between German culture and the corruption of it by fascism. Nobody now blamed long-dead composers for where they were born”.

The audience was socially diverse. Hess recalled a young sailor who had been wandering around Trafalgar Square, saw there was a concert on and went inside; he and his colleagues then returned whenever they had a day’s leave. As Hess herself said in 1949, “nobody told them that a Beethoven or Mozart quartet was high-brow, or beyond their understanding; they just sat back, listened, and a new world opened to them.”

These were more sensible times, when nobody bleated on about “elitism”, and when it was possible for a determined, no-nonsense artist such as Hess to do genuine good without making a song and dance about it. To read about the post-war termination of the concerts, against this extraordinary woman’s wishes, is genuinely moving.