Twenty years after it deluged New Orleans and ravaged other Gulf Coast communities, Hurricane Katrina continues to hold central lessons for U.S. disaster response – including cautionary ones, as Washington may be poised to scale back federal aid for emergencies.

At issue is whether states or the federal government should bear more responsibility for disaster relief – including help for those most vulnerable to events like storms and floods.

The issue is gaining urgency from rising disaster costs. The number of billion-dollar storms has risen from three in 1980 to 25 in 2023. But even today, Katrina stands as the most expensive natural disaster in U.S. history, at over $200 billion in damage.

Why We Wrote This

Hurricane Katrina was a wake-up call for states as well as for federal disaster response. Lessons in resilience have born fruit, but a proposed scaling back of FEMA’s role is stirring debate in an era of rising storm costs.

For many of those who were there, the scale of destruction felt apocalyptic, even as it took days for many outside New Orleans to grasp the enormity of the storm’s toll. What’s more, Hurricane Katrina didn’t just open the curtain on inequities born of class, race, and wealth – it ripped the whole curtain away.

“While Katrina was singular and extraordinary, it was also a bellwether for these other events that play out in the same way: An extreme weather event exacerbated by human impacts on the environment comes up against infrastructure never meant to withstand it,” says Brooklyn-based filmmaker Traci Curry, who directed National Geographic’s “Hurricane Katrina: Race Against Time.” “The result is the people who have the most vulnerabilities have the least ability to recover.”

Katrina spurred changes at FEMA and beyond

The storm led to reforms to the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Congress mandated that the agency’s leader have emergency management experience, though today the senior official performing the duties of FEMA administrator, David Richardson, has no such background. A clunky top-down command structure at FEMA morphed into a nimbler bottom-up approach, using citizens, nongovernmental organizations, and religious organizations in an all-hands-on-deck manner.

Perhaps most notably, the determination by New Orleanians to take a stand in the vast Louisiana marshes helped to spark a resilience movement that spans the United States from coastal cities to creekside towns. At least 13 states now have disaster resilience offices. Coastal cities from Charleston, South Carolina, to Tampa, Florida, have taken major mitigation steps to counter rising sea levels that threaten residents.

Those efforts suggest a national will to address “challenging questions about what we’re willing to accept as risk but also layering in the really important issue of [people’s] deep place attachment,” says Gavin Smith, an expert on disaster recovery at North Carolina State University in Raleigh.

Responsibility shifting to the states?

After criticizing the federal response to Hurricane Helene last October, the Trump administration has prioritized emergency response reform, aiming for a downsized federal role to spur stronger state defenses. A bill in Congress would mandate that if states make approved investments in disaster mitigation, FEMA could cover up to 85% of recovery costs. Without those improvements, reimbursement would drop to 65%.

Such efforts are in part an admission that the “trajectory of the feds taking on an increasingly larger and larger share of responsibility toward disaster management is untenable,” says Aaron Clark-Ginsberg, a disaster resilience expert at the Rand School of Public Policy in Santa Monica, California.

At a July congressional hearing, Mr. Richardson, FEMA’s acting administrator, defended the agency’s response to the deadly floods in the Texas Hill Country, saying it was a model for putting financial and logistical control in the hands of states. But critics say the agency took over 72 hours to marshal its search-and-rescue crews and lacked call center support. Answering the criticism, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said the state efforts in Texas nullified the need for the federal teams and said the call center reports were “fake news.” And, after an Arkansas tornado outbreak this spring, the administration at first rejected an emergency declaration to provide help, but then approved the declaration a month later.

Accounts like those have raised concerns about the limits of a more detached federal posture that could fail to take into account the varying resources and capabilities of states.

This week, dozens of current and former FEMA employees posted an open letter saying that poor management at the agency is risking another Katrina-style disaster. A number of those employees have since been placed on administrative leave, and Secretary Noem, taking a cue from President Donald Trump, is pledging to eliminate the agency “as it exists today” and improve U.S. emergency management.

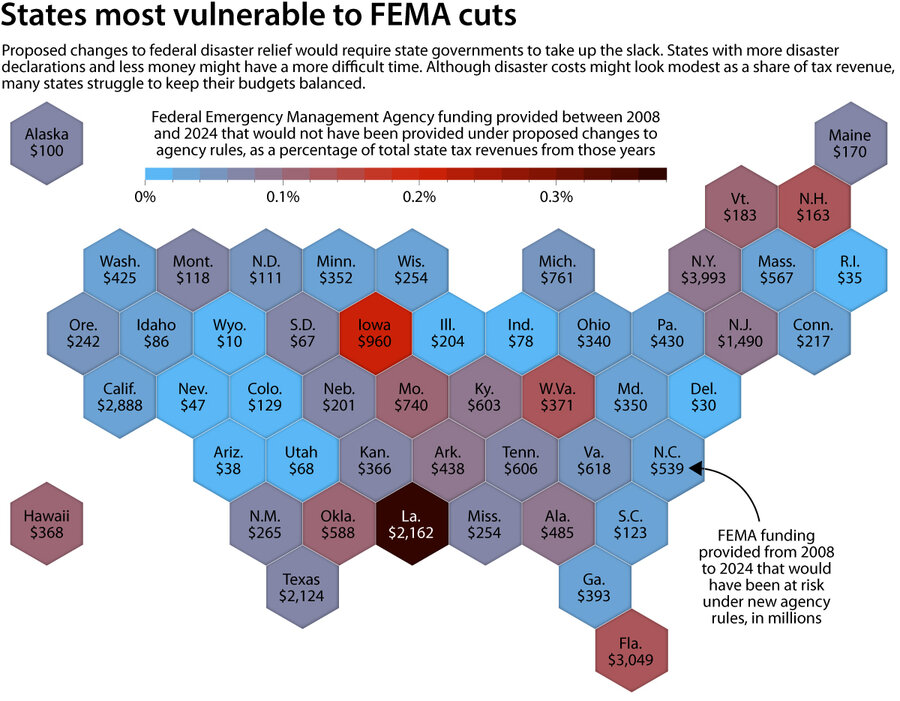

Under cost shifts proposed by the Trump administration, Florida would have borne $563 million in additional costs after Hurricanes Ian and Nicole in 2022, equal to about 21% of the state’s rainy-day fund. Louisiana would have seen its whole rainy-day fund wiped out, without FEMA funding for a series of storms in 2020 and 2021.

“The basic idea [of resilience after Katrina] is, let’s not get siloed in, let’s work collectively to reduce risk and improve preparedness – let’s respond together and recover together,” says Professor Clark-Ginsberg. “The downside is that resilience can sometimes be an excuse for abandonment – that disasters happen, and it’s up to you to pull yourselves up by your bootstraps to survive.”

Rising efforts in North Carolina, Texas

States are adapting to the new reality, with efforts including a North Carolina bill to create a new centralized emergency response office. It’s a big deal because North Carolina has historically been on the leading edge of disaster relief policy, going back to Hurricane Floyd in 1998. Texas has bolstered its disaster response infrastructure after a series of hurricanes and snowstorms. Last year, Georgia began exploring a resilience office by looking at the experience of the state’s tiny Tybee Island, where City Hall has used federal funding and grants to improve stormwater management as surrounding seas rise.

Louisiana in many ways set the tone for these efforts after Katrina, when it created the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, and New Orleans pioneered the creation of a chief resilience officer and an Office of Hazard Mitigation.

Today, the Crescent City is far better protected, in large part because residents crossed political and cultural barriers to “not just say what they didn’t want, but what they did need,” says Mark Davis, director of the Tulane Center for Environmental Law.

“It made it clear to a lot of us that it wasn’t enough to love New Orleans and south Louisiana,” he says. “You had to take care of it. And that comes with responsibility.”

A key question is, Will states muster the ability to pay the price? Complicating the issue is that the demographic center point of the U.S. has started leaning South, putting people and their homes into places that experience more hurricanes or other extreme weather. Since 2015, Texas, Louisiana, and Florida – all Republican-led states in the South – have received the most individual assistance payments from FEMA: more than $2 billion each.

“Even if the climate wasn’t changing and the disaster rate was constant, it would still cost more to address” investments in high-risk areas, because of population growth and construction costs, says Neil Malhotra, a Stanford University economist.

Not long after Katrina passed over the city, Willie Taylor heard the crack of the Industrial Canal as it failed near the Lower Ninth Ward, flooding a community built in large measure by Black longshoremen and their families. After evacuating to a downtown convention center, he ended up in Houston, where he spent seven years working at the airport.

“At first, there was no place to come back to” given the widespread destruction, says Mr. Taylor. It took him years of paperwork to secure a grant for a modular home, where he now lives in retirement, helping to landscape the Lower Ninth in vague hopes of bringing back the homes on Flood Street.

“Houston was OK, but it wasn’t home,” he says. “I don’t know what would have happened if I couldn’t have returned. In a way, I had to make it happen.”

A slightly falling population in New Orleans and the checkerboard recovery in the Lower Ninth Ward reflect a countertrend: Even as more than 17 million Americans have moved into flood-risk areas, about 3.2 million have decamped from flood-risk areas to safer ground between 2000 and 2020 – in some cases leaving folks like Mr. Taylor mowing empty lots to keep the wild from reclaiming them.

Citizens as building blocks of resilience

Even as disasters may force reassessment of where people live, another legacy of Katrina is an awareness that citizens will rally to support one another.

Random Cushing remembers, as an 8-year-old, his hometown hosting people displaced from a city he had never heard of: New Orleans. Today, Mr. Cushing is a street poet in the city, pulling his knees up to a portable Olivetti in the city’s Jackson Square. A sign on the tiny desk reads, “Poems For Strangers.” He is part of the “layers of the city,” as he puts it.

Such connections are a humanizing force – and an important bulwark of resilience as the nation faces increasingly complex disasters.

Referring to the goodwill that was extended to so many people displaced by Katrina, Ms. Curry, the filmmaker, says, “I just wish we could bottle that sort of spirit.”