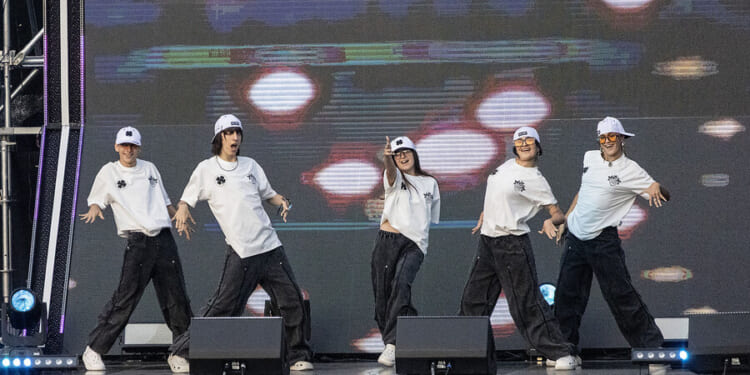

Crowds gather in Seoul to watch teams from around the world duke it out in a first-of-its kind showcase of agility, strength, and style.

This isn’t the Summer Olympics. It’s a dance-off.

The 2025 Seoul Hunters Festival, held at Seoul Plaza, attracted artists from the United States, Bulgaria, Indonesia, and beyond to celebrate the hit animated film “KPop Demon Hunters.” Dance troupes performed high-energy choreography to the movie’s original synthy soundtrack, interspersed with singing and tae kwon do showcases. Between each act, participants discussed their favorite aspects of Korean culture, such as the spicy instant noodles available at 24-hour convenience stores (and featured prominently in the movie).

Why We Wrote This

Soft power can’t replace military force, but it can go a long way toward bolstering a country’s international status. Look no further than South Korea’s K-pop reach.

It was a dazzling display not just of this film’s success, but of the immense soft power that South Korea has accumulated over the past few decades – and which President Lee Jae Myung now hopes to harness. He launched a new presidential advisory body this month to help promote Korea’s cultural exports, and has made K-pop culture a central theme of this week’s Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in Gyeongju, South Korea.

Leaders believe Koreans’ deep well of creativity – developed in part from a history of hardship and colonialism – is now helping safeguard the country. “When it comes to Korean arms exports or defense industry cooperation,” says Seok Jong-gun, minister of South Korea’s Defense Acquisition Program Administration, many countries “place high trust or credibility in Korea because of the soft power.” By fostering affection for the country as a whole, “K-culture can ultimately contribute to national security, which means that we can make Korea a safer place,” he adds.

The Korean Wave

South Korea has traditionally lacked “hard power.” For much of its history, it was a poor country, frequently invaded by surrounding powers. Even today, it faces a declining population and a nuclear armed rival directly to its north. Yet the international success of its music, films, TV, and video games has helped raise its global standing.

The world’s obsession with all things K-culture began after the 1997 Asian financial crisis brought the Korean economy to a halt. Leaders knew that South Korea needed to diversify its economy. At the same time, new South Korean music and television programs were finding popularity in China, where journalists coined the term Hallyu, or Korean Wave.

So in 1998, South Korea’s president launched the “Hallyu Industry Support Development Plan,” a sort of soft power playbook that laid the groundwork for its art and culture to flourish, particularly overseas. And it worked.

The Korean Wave first swept through Asia, then reached the Middle East and parts of Europe, helping reboot South Korea’s economy and its global reputation. In 2012, it galloped into the United States with singer Psy’s viral “Gangnam Style” music video.

The satirical track dominated the internet for weeks, symbolizing “that an outward-looking, cool South Korea had arrived on the global stage,” write Victor D. Cha and Ramon Pacheco Pardo in their book “Korea: A New History of South & North.” “South Koreans rejoiced. Their country was now known for bringing joy and laughter to people everywhere. And yet, Hallyu was only starting.”

In the years since, K-pop idol groups BTS and Blackpink have headlined major music festivals and broken streaming records around the world. Bong Joon-ho’s “Parasite” became the first non-English-language film to win an Academy Award for best picture.

During pandemic lockdowns, the romantic North-South epic “Crash Landing on You” set ratings records and persuaded Americans with Netflix that reading 16 hours of captions not only wasn’t homework; it was key to accessing star-crossed love stories of a depth and complexity not found on the Hallmark Channel.

Since then, popular K-dramas – from the bleak “Squid Game” to the charming “Extraordinary Attorney Woo” – have introduced millions of people to South Korean culture.

Seoul “wants to foster soft power, with the principles of cooperation like openness, inclusiveness, and solidarity,” says Jeonghun Min, a professor at the Korea National Diplomatic Academy. “For South Korea, the soft power, the Hallyu, the universal value of cooperation are very important to mobilize the other middle-power countries to survive against the very strong and aggressive world powers.”

Now “KPop Demon Hunters” – which follows members of the fictional girl group HUNTR/X as they fight to save fans’ souls from a scheming demon boy band – is raking in the accolades. Since its release in June, the action musical has surpassed “Squid Game” as Netflix’s most-watched title, and its top track, “Golden,” was nominated for MTV’s Song of the Summer.

Ho-sung Kang, a former entertainment lawyer who recently launched his own talent agency, KHS Agency, notes that it’s not the government support that makes Korean art resonate around the world, but a creativity born from resilience. “Geographically, Korea is surrounded by big powers like China and Japan … and we’ve gone through multiple invasions throughout our history,” he explains. This history of colonialism, some Koreans argue, has created a culture of han – a complex emotion that has been described as a sort of nationwide longing, and as a sense of hope amid grief.

“Korea has a lot of joy, and when this joy is oppressed, this turns into han, which is a mix of sorrow, angst, and frustration,” says the KHS Agency founder. “And this [depth of emotion] has led to creativity. … It’s in Koreans’ DNA.”

Soft power and the Koreas

The Lowy Institute’s Asia Power Index, which compares how well different Asian countries convert their resources into global influence, ranks South Korea as one of the region’s highest “overachievers” – meaning that it’s punching well above its weight on soft power. North Korea, meanwhile, is the Lowy Institute’s single worst “underachiever.” The authoritarian regime has developed a vast military and nuclear arsenal, but its diplomatic and economic isolation prevents it from reaching its full potential, says the report.

South Korea still imposes two years of mandatory military service on its young men, and nobody sees soft power as a replacement for a strong national defense. Yet South Korea’s cultural exports have been a key tool in fostering goodwill abroad, and foreign policy experts and defense officials say that goodwill makes a real difference.

When DAPA’s Maj. Gen. Seok travels around the world, people he meets are already familiar with Korean culture thanks to Hallyu, and they are more willing to develop business and security ties as a result.

“K-culture is like a sort of a seasoning,” he says. “It can add flavor to the partnership.”

This cultural footing is likely to become more important as Washington embraces an increasingly isolationist foreign policy, and Beijing deepens ties with Moscow and Pyongyang. The two-day APEC meeting this week – which President Donald Trump and Chinese leader Xi Jinping are both set to attend – will be the next test of President Lee’s ability to navigate these new regional dynamics.

He might find that a little K-pop goes a long way.

This reporting was supported by the East-West Center.