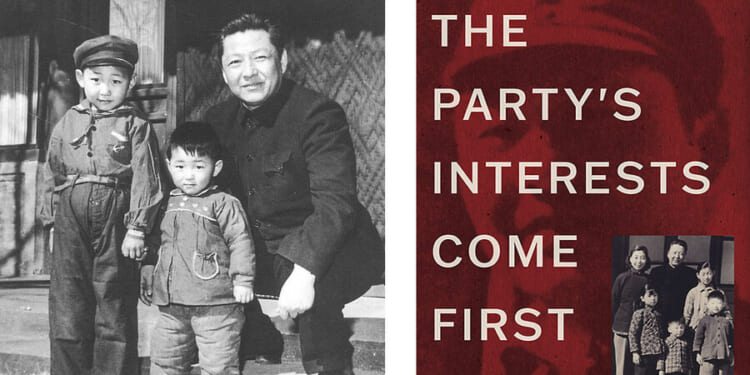

In “The Party’s Interests Come First: The Life of Xi Zhongxun, Father of Xi Jinping,” Joseph Torigian sheds light on the coercive power of China’s Communist Party regime. Drawing on his deep knowledge of authoritarian states, Dr. Torigian, who speaks Chinese and Russian, unravels the mystery of why revolutionary veteran Xi Zhongxun remained so loyal to the party after years of persecution. In doing so, Dr. Torigian offers a nuanced portrait of the elder Mr. Xi, who had a conservative streak despite his reputation as a reform-leading senior official instrumental in pushing forward market-oriented economic and trade policies in the late 1970s and ’80s. This also explains why current Chinese leader Xi Jinping defied early expectations that he, too, would advance reform. The interview has been lightly edited and condensed.

What drew you to write this book?

I wanted to give a picture of what it was like for Xi Jinping to grow up in a revolutionary family. I also wanted to tell the story of the Chinese Communist Party through the life of Xi Jinping’s father, Xi Zhongxun, who was present for many of the most important moments in modern Chinese history.

Why We Wrote This

Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s views were shaped by the experiences of his father, Xi Zhongxun, a revolutionary whom the Communist Party cast aside. Author Joseph Torigian examines the life of the father to shed light on the actions of the son.

How did your expertise in both Russia and China help you with this project?

It’s not easy to research authoritarian regimes, especially China and Russia, but I have tried to develop a set of detective skills. It’s necessary to be sensitive to possibilities and not limitations.

Xi Zhongxun was interesting in part because he played a role in the relationship between China and the Soviet Union. He managed the Soviet expert program in the 1950s, so I needed an ability to access Russian sources. I was able to make a quite complete list of every time Xi Zhongxun met with a foreigner, whether within China or outside China. Then I went to the relevant archives in those countries or even spoke to the person who met Xi Zhongxun, including the Dalai Lama.

As I learned more about Xi, a central puzzle emerged, which is why he remained so loyal to the party, even though it persecuted him so many times, hurt the people around him, and often made choices with which he disagreed.

How would you compare the two generations – the old guard, revolutionary veterans, and their offspring, known as “princelings”?

Both generations went through excruciating experiences. The founding generation fought the Nationalists and the Japanese, were nearly destroyed on many occasions, and saw so many other revolutionaries die before the victory of 1949.

Xi Jinping’s generation underwent the Cultural Revolution. Xi said nobody could ever imagine what he experienced, that there was nothing harder than that, and that it toughened him.

Some princelings were profoundly disillusioned and decided on another life choice, which was to have fun and make money. Others wanted China to move onto a path of constitutionalism and rule of law.

Now the puzzle for Xi Jinping – and it’s an existential one – is how you win over yet a third generation of young Chinese people to the cause. He sees meaning in calls to sacrifice, but we’ll have to see how many young Chinese people find meaning in that the same way he does. What kind of suffering leads to alienation, and what kind leads to dedication?

What does your book tell us about politics inside the top levels of China’s Communist Party, which is often dismissed as a black box?

Well, it’s a black box even for people at the apex of the party elite. One of the most striking findings of my research is how often even very powerful individuals with a great deal of experience don’t have a full picture of what’s going on. And one implication of that is we don’t see factions forming within the elite in a way that many Western analysts have presumed. You don’t know what other people are thinking, and if you do try to act in concert with other people, that’s politically dangerous, because the top leader sees that as a threat to party unity.

The continuities in the Chinese Communist Party are astounding. It’s an organizational weapon, and it always has been. On the other hand, it’s hard to predict the outcome of any particular scenario. There are many intricacies in how the party works, how people think, and how the cards may fall. So it’s both predictable and unpredictable.

Xi Zhongxun was not an ideologue. Would you say that he was less dogmatic than his son?

Xi Zhongxun has a reputation for being more liberal, but he still believed the Chinese Communist Party needed to build a spiritual civilization. He deserves credit for being a reformer, but he was also very conservative in some ways. For example, he at least initially opposed the late 1970s household responsibility system, which reallocated collective farmland to individual families. When Mao Zedong or Deng Xiaoping made decisions with which he disagreed, he still put the party’s interests first and obeyed.