This article is taken from the August-September 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

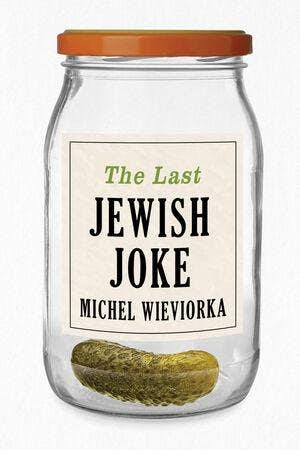

Here’s one. A Jewish gentleman crossing a busy road is hit by a car. As he is lifted onto the stretcher, the ambulance man asks, “Are you comfortable?” He shrugs, winces and replies, “I make a living.” If that tickles your fancy for a melafefon, you should unscrew the lid and dip in.

What’s special about these jokes? The author Michel Wieviorka, of Polish-Jewish descent, sets down three strictures: they may only be created by Jews; only a Jew may tell them; the jokes must not be anti-Semitic (he drops the second of these early on in the book). The subject matter typically includes marriage, the materfamilias, money, death and traditional livelihoods — e.g. tailoring, the synagogue, the deli.

Jokes do the rounds about stingy Jews, just as they do about tight-fisted Scots and miserly Yorkshiremen, but, whereas the butt of a joke is jeered at and mocked, something else seems to be at play in the Jewish joke. Try this: “You see this watch? I treasure it … my grandfather sold it to me on his deathbed.”

The joke has a Jewish target, but is it scornful? The humour expresses pride and a residual spirit of stoicism passed down from the shtetl. Freud noted the self-criticism and collective misery in Jewish humour. Room for a little nostalgia too?

Two principal archetypes feature in the jokes: the schlemiel is the clumsy, socially-awkward underdog; the schlimazel is unlucky, circumstantially, usually through association with the former. The first one spills the soup; the second one has the soup land on him. This dynamic plays out with George, or Kramer, and Jerry in Seinfeld (e.g. the Puffy Shirt episode).

Early film roles of Woody Allen are a catalogue of clownish failures, Chaplinesque endeavour and loss of control: attributes of the schlemiel plus a splash of the absurd (e.g. Take the Money and Run, Bananas, Sleeper). This preoccupation with misfires and non-fulfilment is summed up by the historian of comedy, Judith Stora-Sandor: “Jewish humour finds its source in misfortune.”

The Borscht Belt was a string of Jewish-friendly resorts in the Catskill Mountains, a three-hour drive upstate from New York, where families went to “breathe the air of Jewish comedians” (Adam Biro). Generations of performers — the Marx Brothers, Danny Kaye, Phil Silvers, Victor Borge, Joan Rivers, Jerry Seinfeld — honed their act or played there as big names. At its peak, in the 30 years after World War ll, it was the major proving ground for Jewish showbusiness talent.

Beyond the hotels and bungalow colonies, the comedians developed wider exposure through radio, film and TV to Jews and Gentiles alike. The urbanite, street-smart, wise-cracking Jew became the new comedic Everyman. In 1965, Esquire magazine named this the “Yiddishization of American humour”.

Why did the Borscht Belt decline? As the Jewish diaspora assimilated, visitor numbers dwindled — and, by the 1980s, most resorts were defunct. The new Jewish livelihoods were to be found in academia, law and medicine, and there was less need to gather together in numbers for rest and recreation. A generational shift led to younger Jews holidaying at destinations reachable by cheap air travel.

More broadly, the high esteem with which the state of Israel and Jews were regarded — the impact of Leon Uris’s Exodus; the capture, trial and execution of Eichmann; the Six Day War — waned. The image of the brave, young nation has inevitably become tarnished due to the increases in and intensification of conflicts with Hamas and its regional allies. Now anti-Semitism “finds a renewed space on the left”. At a mundane level, political correctness and the onset of woke culture have engendered a zeitgeist inimical to joke-telling.

As Maureen Lipman might say, the author has an “ology”. There is much Senior Common Room chat and too few good jokes. An anglophone readership will likely take little interest in talk of French academic conferences or spats between professors. The jokes are there to illustrate a serious point, I get it. However, they need to be shorter, punchier and funnier.

Similarly, the leading US comedians deserve some biographical coverage: Mel Brooks fought in the Battle of the Bulge and saw starving Jewish refugees. He went on to ridicule the Nazis joyfully and mercilessly in The Producers (1967).

A witz to finish on. Tevye, the eponymous Fiddler on the Roof, begs of God: “I know, I know, we are the chosen people … but, once in a while, can’t You choose someone else?”

It is right and proper that the flag flies for Jewish jokes. Our entertainment culture would be poorer without them. A cheer or two, then, for Michel Wieviorka.