Hundreds of slips of black paper swarmed the sky over Gaza City on Tuesday morning, then fluttered down onto its bomb-blasted streets. Printed on each was the same curt order from the Israeli military.

“To the residents of Gaza City: … For your safety, evacuate immediately.”

As Israel presses a major offensive to take control of the city, the reasons for residents to follow its orders were clear.

Why We Wrote This

What leads people to disobey an evacuation order? In Gaza City, many residents say there is simply no place to go.

But very often, the decision was not.

“Displacement is the war itself,” explains Ayman Al Otol, a father of eight whose family has spent the past two years moving around Gaza City in search of safe places to shelter. Today, the family lives in a tent in the former commercial district of Saraya, where makeshift encampments fill streets that once bustled with shoppers, office workers, and families.

“The war is not about airstrikes,” he says. “We have become numb to that. It is about moving from one place to another.”

* * *

By the time the evacuation warnings fell from the sky, many here had already been debating the decision to stay or go for weeks. Two weeks ago, a hunger-monitoring agency backed by the United Nations declared a famine in Gaza City.

In mid-August, the Israeli cabinet approved plans for a sweeping takeover of Gaza City, designed to eliminate what it says is Hamas’ last remaining stronghold in Gaza. In the days that followed, the Israeli military called up 60,000 reservists, and began blowing up high-rise towers in the city that it said Hamas fighters were using as lookout points. The buildings used to shelter hundreds of Palestinian families.

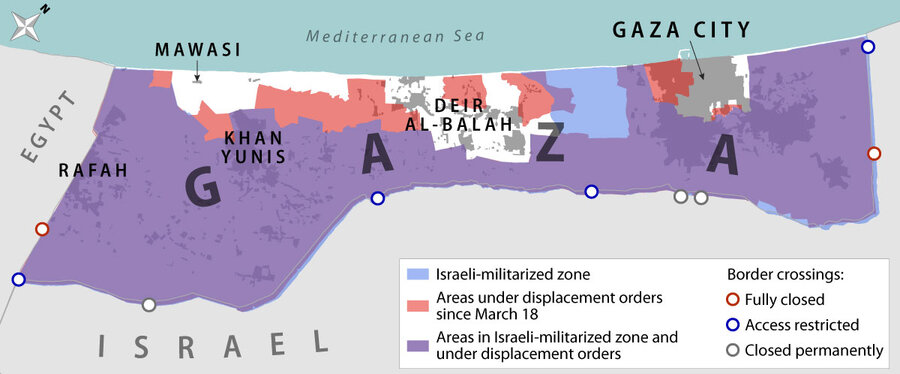

The military urged Palestinians to evacuate to a hurriedly resketched “humanitarian corridor” in southern Gaza. It included the decimated city of Khan Yunis, as well as neighboring Mawasi, a makeshift displacement camp on a strip of sandy coastline that already has a population density of about 121,000 people per square mile, and is almost entirely without sewage, running water, or medical facilities. Despite being declared a safe zone for civilians, Israeli forces have repeatedly shelled and rocketed the area, as recently as May of this year.

For many Gaza City residents, fleeing to Mawasi feels no safer than staying put.

“They bomb everywhere,” says Nadia Abu Hjeila. Since October 2023, she had been displaced nearly 10 times before finally returning here, to the rubble of the city where she was born. Now, the mother of seven is firm in her decision. “Since there is no safe place, I will not move,” she says. “At least here, we stay with dignity.”

But standing beside Ms. Hjeila, her daughter Iman isn’t as sure. Displacement, she agrees, “was unbearable. Days and nights without water, without food, surrounded by disease and death. Every time we try to settle, we lose everything again.”

Still, as the younger Ms. Hjeila hugs her infant son against her chest, her resolve slackens. “I am afraid I might lose my child [if I stay] here,” she confesses.

* * *

By the beginning of this week, Israel had taken control of about 40% of Gaza City, and claimed to have destroyed at least 50 high-rise residential buildings.

“Staying in the area is very dangerous,” warned the fliers that rained over Gaza City on Tuesday. But on the ground, there seemed to be little fear.

Women kept hair appointments at their local salons. Couples prepared for wedding parties. Local supermarkets advertised their weekly specials, and neighbors bickered over their fences about who left garbage in their yard.

For many, the decision to stay put was simply practical.

A move would cost enormous sums of money. Renting a truck to transport a family’s belongings would cost around $1,000, and buying a tent to pitch at Mawasi would cost another $1,000. And the move would further drain emotional resources long ago spent.

“The situation is horrific right now, but I can tolerate it. I can tolerate it more than being displaced,” explains Dana al-Lababidy, a university lecturer.

“We are already exhausted, mentally broken, disappointed, and desperate,” says Mr. Otol. In the past two years, his family has already been uprooted four times. One of Mr. Otol’s adult sons, injured by Israeli soldiers, can no longer walk. It takes eight people to carry him on a mattress, making it extremely difficult for the family to move. “I always think of him, of his safety,” Mr. Otol says. “The fear of losing him never leaves me.”

For her part, the elderly Ms. Hjeila was simply tired. “Gaza City is my land,” she says. “If we die, we die here.”