Steven Spielberg will forever be known as the great catalyst for what has become a rapidly expanding and controversial super-luxury marketplace.

The US movie mogul’s 1993 film, Jurassic Park, and the ensuing franchise sparked a worldwide interest in dinosaurs and led to a surge in fossil trade.

And it’s continued ever since. Let’s say you’ve got a private jet and helicopter, a yacht with full crew moored in the south of France, an original Picasso line drawing… how about a 125 million-year-old skeleton of a dinosaur as the centrepiece for your marble hall?

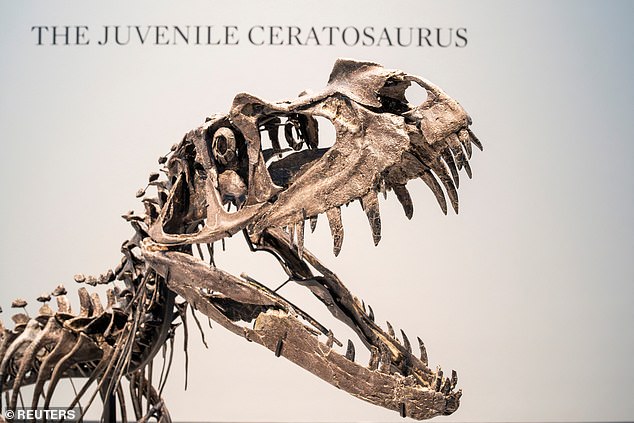

Last month, one such skeleton fetched more than $30million in a bidding frenzy at Sotheby’s in New York. The mounted young Ceratosaurus nasicornis – from the Kimmeridgian period some 150 million years ago – had a pre-auction estimate of $4million to $6million, in part because it is one of only four known skeletons of the species and the only juvenile. It resembles the Tyrannosaurus rex but is smaller.

Bidding started with an offer of $6million, then took off until the official sale price reached $30.5million, thanks to an anonymous buyer. There were sharp intakes of breath and those in the room applauded after the auctioneer’s hammer came down – but not everyone was happy.

For Steve Brusatte, a professor of palaeontology and evolution at the University of Edinburgh, the price tag is shocking.

‘Who has that kind of money to spend on a dinosaur? Certainly not any museums or educational institutions,’ he says. ‘While I’m pleased that the buyer might loan the skeleton to a museum, at this point it is just a vague suggestion. My fear is that it will disappear into the ether, into the mansion of an oligarch or a bank vault to accumulate value as just another investment in the portfolio of a hedge fund.’

Warming to his theme, Mr Brusatte, an American who specialises in the anatomy and evolution of dinosaurs, says: ‘I worry about the longer-term negative repercussions for museums and fossil collecting. This fossil had been on display in a private museum that was experiencing a budget crunch, and they decided to sell it. Will this now become a strategy when museums are trying to balance the books and they just sell their dinosaurs to millionaires?’

Steve Brusatte, a professor of palaeontology and evolution at the University of Edinburgh, said he fears the dinosaur skeleton sold at auction ‘will disappear into the ether’

Steven Spielberg’s film Jurassic Park sparked a worldwide interest in dinosaurs and led to a surge in fossil trade

The juvenile Ceratosaurus nasicornis sold at Sotheby’s Natural History auction in New York in July

Mr Brusatte believes that a world where dinosaur skeletons can fetch tens of millions of dollars within a few minutes at auction is a world that doesn’t understand the value of education and research. It’s a victory for the trophy culture.

‘These amazing skeletons will become playthings for the uber-wealthy, and in many ways, they already are,’ says Mr Brusatte.

He has a point. Last July, a dinosaur fossil named Apex made headlines when it was sold for $44.6million at Sotheby’s, making it the most valuable ever sold at auction.

The 150 million-year-old stegosaurus measures 11 feet tall and nearly 27 feet long from nose to tail and is a nearly complete skeleton with 254 fossil bones.

And who was the buyer? None other than the billionaire investor Ken Griffin, founder and CEO of giant hedge fund Citadel. But, much to the relief of the worldwide paleontological community, Griffin did the honourable thing and handed it over to the American Museum of Natural History for the next four years so it can be studied and made available for public viewing.

Then, there’s the celebrity factor, which in the case of Oscar-winning actor, Nicolas Cage, came back to bite him. He paid £185,000 for a Tyrannosaurus bataar skull (a cousin of the T. rex) in 2007 after outbidding fellow thespian, Leonardo DiCaprio, while Russell Crowe, another well-known fossil collector, watched from the sidelines.

Although Cage bought the skull from a Beverly Hills gallery and was issued with a certificate of authenticity, it turned out to be stolen from Mongolia and was returned to the government there eight years later.

The rules vary dramatically from country to country. In the US, fossils found on private land belong to the landowner, but it’s finders keepers in Britain as long as the landowner gives permission for the search.

Last year, billionaire investor and hedge fund owner Ken Griffin bought a 150million-year-old stegosaurus for $44.6million at Sotheby’s, making it the most valuable ever sold at auction

Fossil hunters on the beach at Charmouth, Dorset. The British interest in fossils goes back hundreds of years but before the end of the 18th century there was limited understanding of what they were. They were often regarded as ‘curiosities’

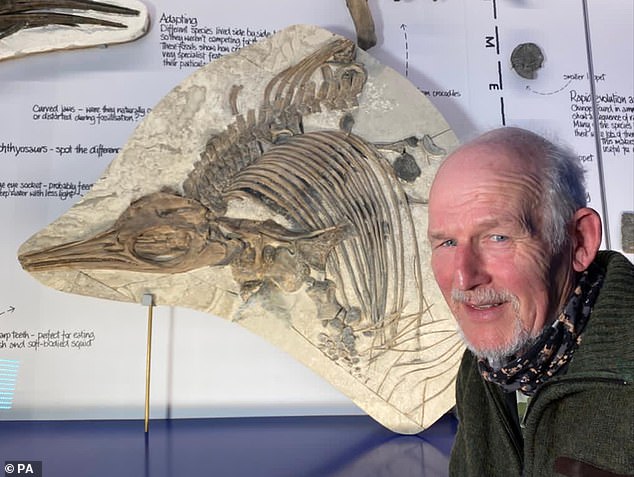

Legendary British fossil collector Steve Etches says ‘we don’t need more rules and regulations’ on fossils as ‘we have far too many of those in this country already’

On the Jurassic Coast in Dorset, fossils found on the shingles by the water line – which is Crown land belonging to the monarch – can be kept without seeking permission, but anything embedded into the cliff face is considered to belong to the owner of the land above the cliff.

Rules are far stricter in China, Mongolia, Brazil, Italy and France, where valuable fossils are regarded as national treasures irrespective of who owns the land. Regulations are also tight in Morocco but seldom enforced and there have been examples of fossils being stolen from sites under government control.

‘We need a reporting system in this country whereby you are obliged to offer what you find to a museum or other public body for the price of what the excavation has cost you,’ says Dr Susannah Maidment, principal researcher in fossil reptiles at London’s Natural History Museum.

But that argument is given short shrift by legendary British fossil collector Steve Etches, who with the help of lottery fund money, founded the Etches Collection Museum of Jurassic Marine Life, in Kimmeridge, Dorset, in 2016.

‘We don’t need more rules and regulations. We’ve got far too many of those in this country already,’ says Mr Etches. ‘There’s nothing wrong with an open market and if very wealthy people want to spend their money on rare fossils then that’s fine. They will likely end up in a museum anyway once the person is dead.’

Mr Brusatte is also against further regulation: ‘It could lead to creating more of a black market.

‘It’s a tough issue and what we really need is a cultural change where those wealthy enough to buy dinosaurs donate them to museums and support science as part and parcel of buying these fossils.’

On the West Dorset coast, the ‘Fossil Collecting Code of Conduct’ recognises the ‘essential need for fossil collecting to continue’ but also ‘recognises that collecting must be carried out in such a way as to satisfy all those with an interest in our fossil heritage.’

Fossil hunters are asked to register any special findings at the Charmouth Heritage Coast Centre – but the fossil remains the property of the person who found it.

The British interest in fossils goes back hundreds of years but before the end of the 18th century there was limited understanding of what they were. They were often regarded as ‘curiosities’.

The early 19th century witnessed a huge shift, prompted to a large degree by the work of Mary Anning, the famous palaeontologist and fossil collector who ran a successful business in Lyme Regis, Dorset. Her story was told in the 2020 film, Ammonite, starting Kate Winslet as Anning and Saoirse Ronan as her love interest.

Another turning point came in 1997 when Sotheby’s auctioned a T. rex fossil named Sue for a whopping $8.4million, making her the most expensive fossil ever sold at the time. Sue was almost a complete skeleton – and not just a collection of old bones.

Trade has burgeoned ever since and today the luxury fossil market is worth billions of dollars.

‘Collectors at the top of the market seem to be seeking out “statement pieces”’, says Dr Mark Westgarth, professor of History of the Art Market, at Leeds University. ‘Large-scale dinosaur fossils allow new “art” collectors to demonstrate their symbolic power.’

But it’s not just the super-wealthy who are becoming increasingly interested in fossils. I happened to be on the Jurassic Coast a few weeks ago. It rained most of the day on Sunday – but Charmouth Beach (within the country’s first natural World Heritage Site and along the coast from Lyme Regis) was packed with men, women and children of all ages scouring the shore line in search of treasure, amid the tap-tap of fossil hammers.

‘If you had more regulation it would dampen people’s interest in fossils. It wouldn’t spark the imagination in the same way,’ says Grant Field, manager of the Charmouth Heritage Coast Centre. ‘We’re now getting more than 100,000 visitors a year and they are finding precious things every day. It’s a wonderful way of introducing people to the natural world.’

This all brings to mind the proposed £80million tourist attraction on the Jurassic Coast, which was planned by former Daily Mail science writer, Michael Hanlon. With the backing of Sir David Attenborough – who took the role of patron – the museum was to be built in a semi-subterranean artificial cavern in a 132ft deep quarry in Portland. But, sadly, Mr Hanlon died of a heart attack in 2016 at the age of 51, and his vision died with him.

Meanwhile, trade in the fossil shop underneath the heritage centre is doing good business. Forget those massive price tags at auction, some little fossils here are selling for a pound or two. A woman then walks in and notices the shop’s stone doorstop with crystals embedded into it.

‘Could I buy that?’ she says, pointing at the stone.

‘You can have it for nothing. There’s plenty more where that came from,’ says the shopkeeper, looking along the Jurassic coast that stretches for nearly 95 miles. ‘I picked it up from the beach 15 yards from the shop.’