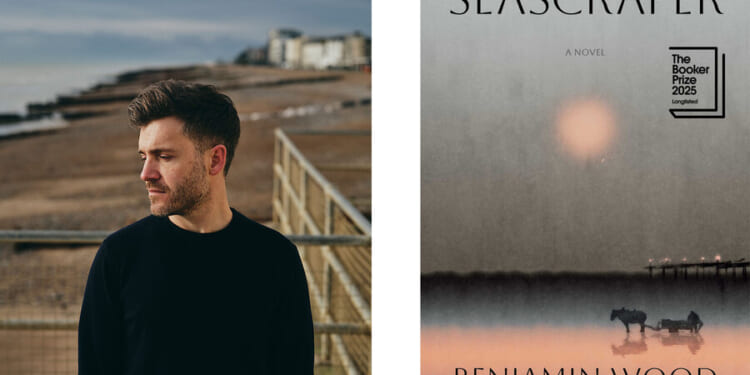

I might have missed English writer Benjamin Wood’s quiet fifth novel, “Seascraper,” had it not reached the longlist for this year’s prestigious Booker Prize. That would have been a pity, because it’s a gorgeous, atmospheric tale about a 20-year-old shrimp harvester who yearns for more out of life.

Set in a fictional coastal town in northwest England called Longferry, (a stand-in for the author’s hometown of Southport), “Seascraper” immerses us in the life of Thomas Flett during what turns out to be an unusually exciting, pivotal day for him. The story feels timeless, though it’s set in the early 1960s.

We meet Tom on a damp morning that begins like every other since he was forced to leave school at age 13 to work alongside his grandfather: Rising well before sunrise, he tends to his horse, bolts the bacon and eggs his mother fries up for him, and heads out in his horse cart under a foggy, predawn drizzle to scrape the shore at low tide for shrimp. He lets his thoughts wander balefully even as he keeps a watchful eye for deadly sinkholes in the rippled sand.

Why We Wrote This

Amid the drudgery of scraping a subsistence from the sea, a man retains an innate sense of his worth and raises his sights.

Tom was raised by his cantankerous late grandfather, who assuaged his disappointments with drink, and by his single mother, Lillian Flett, whom we see through Tom’s critical eyes. Both mother and son are grateful that Pop let her keep the boy despite the enduring disgrace of her pregnancy at age 15.

Although Tom knows that “One day soon, there’ll hardly be a morsel left for him to scrounge up from the beach that can’t be got by quicker means at half the price” – shrimping further down the coast with motor rigs – he’s “the only shanker left in town who’s steadfast to the old ways.”

We trudge along with Tom through the 30-hour span of the novel. We feel his frustration at his monotonous, barely sustainable life. “It bores him worse than it exhausts him,” Wood writes. “It never used to foul his mood this much, the cold, the loneliness, the graft, but that was long before he harboured any aspirations for himself besides what he was raised to want.”

Why the change? Tom was a good student who left school with “an awareness of his own capacity.” He remains an avid reader, and “these past few years, he’s come to understand: he settled for too little.” Tom feels most alive when playing folk music on the beat-up guitar for which he traded his grandfather’s watch. It’s an activity he feels he must hide from his mother, who worries about making ends meet.

“Seascraper” effectively combines two common literary tropes: “A day in the life” and “A stranger comes to town.” The stranger is a fast-talking American named Edgar Acheson who claims to be a Hollywood movie director. Like Harold Hill in “The Music Man,” Acheson talks big. He’s eager to film an old novel called “The Outermost,” and hopes Henry Fonda will play the lead (one of several tipoffs that “Seascraper” is set decades ago). He promises to put Longferry on the map. “I love the bleakness of this place. I’ve never seen a beach so uninviting,” he raves.

Tom, at first skeptical, is entranced. “You could knock on every door in Longferry and never find a man as interesting,” he thinks.

Acheson hires Tom to bring him to the beach at dusk, during the second low tide of the day, so he can take some scouting shots. They’re soon dangerously engulfed by dense fog.

Acheson’s check, paid in advance, is a big windfall for Tom. But whether or not the man turns out to be what he says he is, Tom is grateful for his life lessons. Acheson tells him: “When you’re young, you think life is a string of choices. … You don’t realise that most of what’ll happen to you is because of other people’s choices. … Art’s the only way I’ve ever had of making any sense of it.”

I’ll let readers discover where this is going, but I can say that “Seascraper’s” revelations and epiphanies are well-earned and surprisingly moving. Wood’s novel is a lovely moral tale that recognizes the importance of reconciling practical concerns and necessities with spiritual, emotional ones. It is also about the power of art – music in particular – to uplift and inspire. And it comes with a link to a recording of Thomas Flett’s “cart shanker’s gospel,” a song called “Seascraper.”