In Harvard Square, Tibet’s national flag, with its golden yellow sun and red and blue streaks, billows in the wind while organizers hand out pamphlets about China’s oppression of Tibet. About a dozen others of various generations stand nearby in silent vigil.

Tibetans in Boston have gathered here in Cambridge every week since 2008 to express solidarity with those inside Tibet, who face systemic repression of their language, culture, and history. There were days when Dhondup Phunkhang, a Tibetan who immigrated to Boston more than 20 years ago, would be the only person at these White Wednesday protests. He’s held vigil in rain, snow, and heat.

“It was almost like a meditative practice,” says Mr. Phunkhang. “It solidified my resolve for my belief and people.”

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

Boston’s small, tight-knit Tibetan community is a microcosm of Tibetans living in exile around the world – communities that have fostered a sense of cultural resilience across generations.

Even as the “Free Tibet” movement has largely faded out of mainstream public consciousness, Tibetans have continued to lay down roots in India, America, and beyond. Tight-knit communities like the one in Boston – which has grown from 50 people in the early 1990s to over 700 people today – are hubs of cultural resilience. Elders pass Tibetan Buddhist teachings and traditions onto younger generations who have never set foot in their homeland in Western China. This culture was on full display this week as cities around the world celebrated the birthday of the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s spiritual leader in exile.

“Everywhere in the world, from Toronto to New York to Dharamsala to Tibet, shows that Tibetans have embraced their culture and their identity so strongly,” says Lobsang Sangay, a fellow at Harvard Law School and former president of Tibet’s government in exile. “It’s not like linear regression, you know? So the first generation have strong identity, second generation becomes weak, and the third generation loses it. … In fact, ours is the opposite.”

Nation in exile

The 1950s marked a decade of upheaval for Tibet. China’s Communist Party sought to annex the resource-rich plateau, which would help secure the country’s southwest border. But when Chinese tanks rolled into Tibet in October 1950, local leaders fought to retain their autonomy.

Tensions came to a head during a 1959 uprising, in which the 23-year-old Dalai Lama fled to neighboring India, establishing a government in exile in the northern town of Dharamsala. More than 80,000 Tibetan refugees followed him.

At the time, many hoped for a quick return to their homeland, but that never happened. Today, more than 6 million Tibetans still living in China face what some diaspora and scholars describe as “worse than ever” repression. Tibetans must replace images of Buddhist religious teachers with Chinese political leaders. Children are forcibly separated from parents to enroll in state-run boarding schools, and the Tibetan national anthem is forbidden.

Beyond China’s borders, the Dalai Lama has emerged as a symbol of Tibetan non-violent resistance and a champion for global peace and compassion. He was awarded the Noble Peace Prize in 1989, helping turn Tibetan independence into a cause-célèbre in the West and opening the door for the first wave of mass migration to the United States.

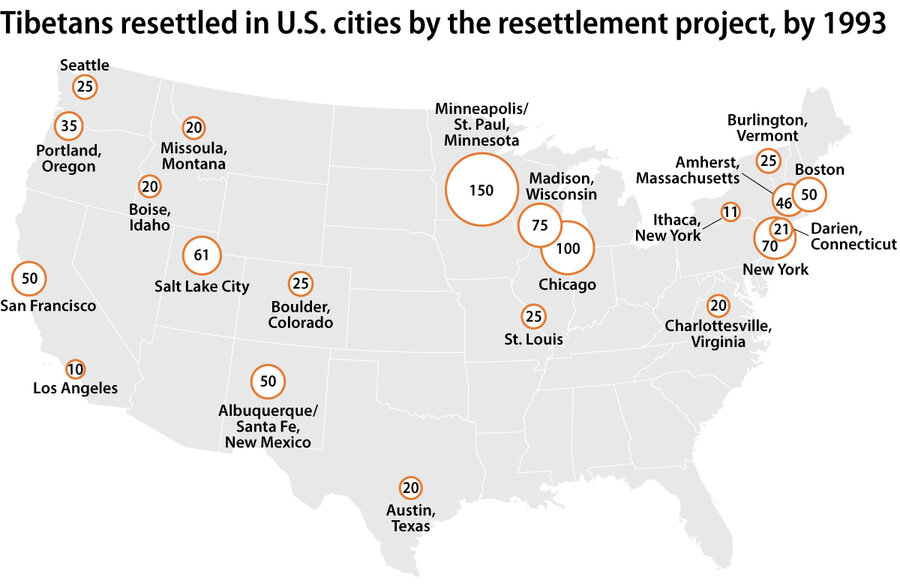

Mr. Sangay recalls how, in the early 1990s, Tibet’s government selected 1,000 individuals to be scattered across 21 “cluster sites” in the U.S. as part of the Tibetan U.S. Resettlement Project. The Dalai Lama gave each of them a small statue of the Buddha.

“You are the ambassador of Tibet,” Mr. Sangay says the Dalai Lama told the volunteers, who were chosen through a lottery system. “You are going to the West, it’s a melting pot, but don’t lose your Tibetan identity. Do the best you can to preserve the Tibetan language, culture, and spirituality.”

Of the nearly 150,000 Tibetans living in exile today, about 26,000 reside in the U.S., according to the Central Tibetan Administration, Tibet’s government in exile. Many Tibetan Americans live in those original resettlement sites, including Boston, where the commitment to preserving Tibetan culture is still going strong.

Reasons to celebrate

As the church bells ring outside the Archangels Greek Orthodox Church in Watertown, Massachusetts, on Sunday, celebrations inside the hall rented by Boston’s Tibetan community are well underway.

Women wear turquoise jewelry reserved for special occasions, and families drape white khatas, a ceremonial scarf, around a portrait of the Dalai Lama. Above it, a cloth tapestry depicting Potala Palace – the traditional winter home of the Dalai Lamas in Tibet – flutters in the air conditioning.

“He’s literally our sun, moon, and moral compass,” says Tenzin Kunsang, an event organizer. “We’re so proud of him, so proud to be Tibetan.”

There were several reasons to celebrate.

Last week, just before his 90th birthday, the Dalai Lama addressed the mounting uncertainty about his succession plans. In a recorded video and written statement, he affirmed that the institution of the Dalai Lama will continue, dispelling speculation that he would be the last to hold the role amid Chinese interference.

In 1995, when the Dalai Lama identified a young boy in Tibet as the reincarnation of the Panchen Lama – an important figure in Tibetan Buddhism who helps identify the next Dalai Lama – China quickly whisked the boy away. His whereabouts are still unknown, and Beijing has installed its own Panchen Lama in his place. When the time comes, many expect the Chinese government to choose its own Dalai Lama.

“What is really happening is [the Dalai Lama] is reminding China that his authority, and that of his successor, comes from a consultative process,” says Robbie Barnett, a professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies who focuses on the history of modern Tibet. “That’s a legitimacy that China can’t compete with – that’s the subtext here.”

The message left many Tibetans feeling “relieved,” says Ms. Kunsang. “No country, no government, no groups shall interfere in this sacred process. We heard that loud and clear.”

As the Tibetan diaspora grows, it’s possible that the next Dalai Lama will be born outside of Tibet – in India, or a city like Boston. Indeed, in his recent memoir, “Voice for the Voiceless,” the Dalai Lama states that his reincarnation will be found in “the free world.”

But that’s far from the minds of the Tibetans who have gathered around large banquet tables in Watertown. Jampa Ghapontsang, one of the first Tibetans to move from Dharamshala to Boston, is simply glad to see Tibetan culture thriving halfway around the world from where it began.

“We are in our third generation of Tibetans, and I just see the growth,” she says, as schoolchildren whirl around the room to traditional music. “For me, it’s a dream.”