Your very first parents’ evening is a daunting prospect for anyone – and for Melanie Lammin it was no exception.

She knew the ropes – probably better than most of the mums and dads at various stages of fury, anxiety and smugness gathered in the school hall that evening – but her heart was pounding for a wholly different reason.

‘You can do this,’ she told herself, trying not to meet the quizzical looks directed her way from the other parents. ‘Shelley needs you now’.

Suddenly the buzzer sounded, and Mel, still only 18, took her 13-year-old sister by the arm and strode with as much confidence as she could muster up to the allotted teacher’s table.

It was the same school she’d attended herself, one she’d left just months ago. Now she was back in her new role: as the teenage legal guardian and ‘kinship carer’ of her little sister Shelley, plus their other sister, Kelly, 16.

Having lost their mother to cancer the year before, Mel – a promising and gifted young woman, with a clutch of high-grade A-levels and a place at Queen Mary University of London to study English – had given everything up to look after her sisters.

In a world where familial bonds are so often taken for granted, and so readily discarded, theirs is a truly humbling tale of the love between sisters being so brutally challenged – and rewarded.

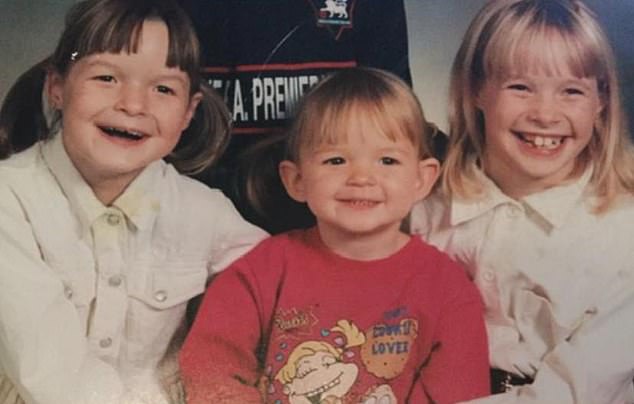

Melanie Lammin (centre) became the carer for her two younger sisters, Shelley (left) and Kelly when she was 18 years old

The sisters had no idea their mother was so desperately ill when they were children

‘I certainly would never have chosen to put myself into that position’, says Mel, now 36, ‘but I knew if my sisters were going to have any chance at a happy future outside of the care system, I was their only chance.

‘Along with school proms, graduations, all those milestones parents normally experience alongside their teenage children, that first parents’ evening was one of the first challenges on my road as a kinship carer – a role that I now look back on with extreme pride, but at the time was impossibly hard.’

Impossibly hard indeed. There are currently more than 141,000 children in kinship care in England and Wales. But unlike foster carers, kinship carers – family or friends who become a child’s guardian in a time of crisis – receive little or no financial support.

Life for this particular family, growing up on a council estate in Dagenham, Essex, had been hard for years.

Their mother Janet was first diagnosed with breast cancer aged 38 when the girls’ older brother, Terry, was nine, Mel was six, Kelly, four, and Shelley just a baby.

It was a particularly cruel blow coming after their father, also called Terry, broke up with Janet and left the home, leaving her struggling as a single mother of four children.

At first they had no idea their mother was so desperately ill.

‘Nobody ever told us it was cancer, that we might lose her,’ remembers Mel. ‘I guess everyone thought we were too young to understand. As her treatment continued, the cancer seemed to go and then came back to take her, by which time we were certainly old enough to understand.’

As their mother’s health deteriorated, Mel found herself shouldering the majority of the household chores – cooking, cleaning and shopping – which she managed to fit around her school work.

By then their older brother had his own life and was barely home, so, says Mel: ‘It kind of fell on to me – not because I was being some kind of saint, they were just things that had to be done, and Mum couldn’t.’

While she plays down her sacrifice, what Mel gave up was considerable. Invitations to hang out with friends or go to parties were refused – everything a 16-year-old girl should be enjoying was denied her. She had neither the money nor the time.

‘Our only trips out were to the park or something like that, where I’d see normal families and wonder what their lives were like compared to our house of ill health and sadness.’

Mel threw herself into her studies as an escape, getting nine GCSEs.

In 2006, their mother finally died aged 49 in a hospice, with her daughters at her bedside. The girls were 17, 15 and 12.

‘I felt shock even though we knew it was coming,’ says Mel. ‘I also felt guilty and a sense of regret that Mum and I had never really talked properly in those final years and months. I’d just been too busy keeping everything going.

‘I knew things were going to change in a massive way because, while Dad was going to move back in with us to deal with some practicalities, it would be up to me to look after Kelly and Shelley on an emotional level. There was just a crushing fear of the unknown, of what would happen next.’

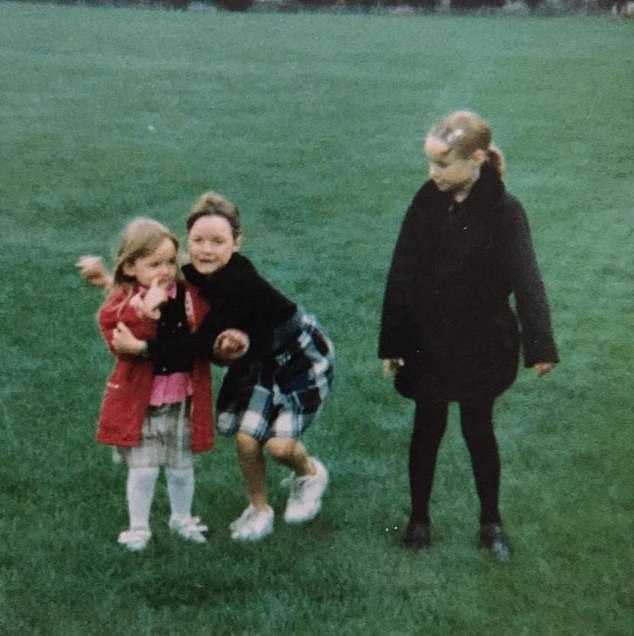

As their mother’s health deteriorated, Mel found herself shouldering the majority of the household chores

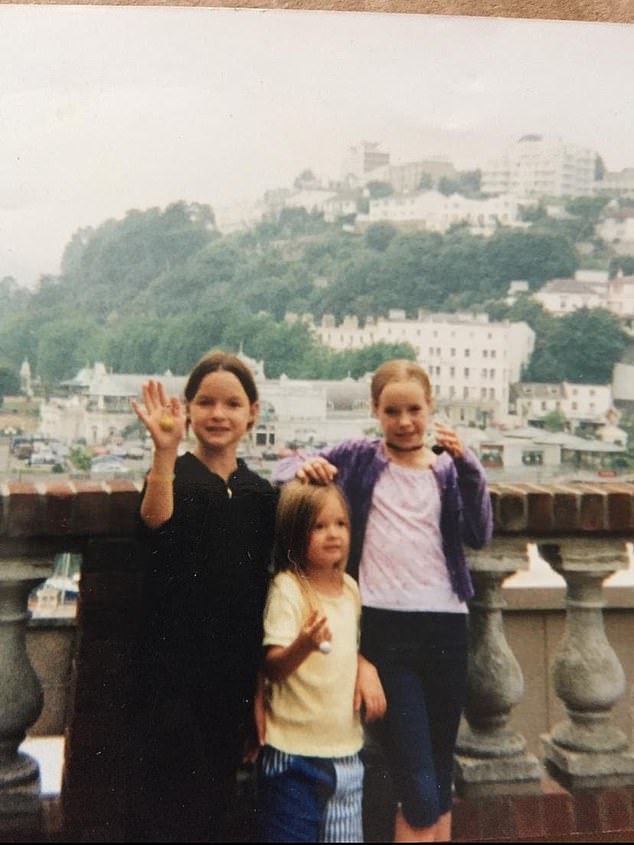

Mel, who was 17 when her mother died, was adamant her younger sisters shouldn’t go into care

While Terry moved back in for a while, he struggled to be the father his children needed; his mental health was in crisis and bills weren’t getting paid.

‘It became obvious that Dad couldn’t fill the hole Mum had left, he wouldn’t be what we needed,’ says Mel, who was then in the lower sixth at school.

Soon, Terry rescinded parental responsibility and moved out. With their older brother by now estranged, the first thing that needed to be sorted out was who was going to look after the children – and Mel was adamant her younger sisters shouldn’t go into care.

‘To get through this we had to stay together as a family. There’d been so much disruption, so for them to leave their school, friends, everything they knew, it would be simply unthinkable.

‘Strangely, I’d felt more pressure when Dad was here than when he was gone; at least now I could take control of what had become an even worse situation – Kelly and Shelley needed some stability.’

Mel had recently started seeing a boy called James, who, she says ‘became so much more than a boyfriend’ in the years that would follow. With the help of James’s stepmother, Pam, appointments were arranged with a solicitor working with social services.

‘By then I’d turned 18 and had given up my dream of going to university. I knew Kelly and Shelley would be taken into care on the other side of London, and they deserved better,’ she explains.

‘Telling social services I wanted to take care of them as their legal guardian, we organised a “family group conference” with my dad, teachers from my school and James’s family.

‘I argued the last thing Kelly and Shelley needed was to be uprooted away from their school and friends when they were also dealing with losing their mum.

‘James and Pam fought my corner and eventually I was awarded a residence order, so I was their legal guardian until they were 18.

‘I was scared and felt so isolated and alone, being so young and inexperienced. I just knew I had a massive and frightening time ahead.’

Certainly the transition from being a big sister to taking on a mothering role was confusing and challenging for all of them.

Certainly the transition from being a big sister to taking on a mothering role was confusing and challenging for all the Lammin girls

Mel had given up a place at Queen Mary University of London to study English so she could look after Shelley and Kelly

‘The lines were so blurred, especially with discipline. Kelly might be out with friends and come home late; I didn’t want to upset her and not tell her to go out or ground her, but she had to know she’d done something wrong,’ says Mel.

Despite James – by then studying theology in London while working part-time – and his family helping where they could, Mel only had about £70 a week in benefits to support herself and her sisters.

‘There weren’t food banks back then, and I was too proud to use charity shops because I didn’t want my sisters to feel inferior, so would spend hours looking for deals for clothes or other essential household items.

‘Pam showed me how to budget, how to cook healthy, cheap meals. My sisters never once made me feel like they were going without – even on birthdays and at Christmas, just a card with a lovely message in it was enough because they knew how tight money was.’

Yet still there were occasions when Mel would go without food, just so her sisters could eat.

Understandably some days, exhausted, lonely and plagued by anxiety, Mel admits she wondered when this would all end, when she could have her life back.

While she did her best to hide her emotions from her sisters, it was James’s shoulder she’d often cry on at night, and she credits him with helping her make it through.

‘He recognised I needed professional help – which had never been offered to any of us after Mum died – so personally paid for me to start bereavement counselling. I carried on with those weekly sessions for two years and while they really helped, my anxiety would regularly resurface.’

Despite sacrificing her own academic ambitions, Mel was incredibly proud when Kelly and then Shelley did brilliantly at their GCSEs and A-levels, both going on to university.

‘I never felt angry or bitter because they’d had that chance when I hadn’t,’ she says. ‘Being there for their graduations, even though I was no longer their kinship carer or legal guardian, I felt like my heart would burst.’

Only now, as grown women with successful careers and lives of their own, can Shelley and Kelly fully appreciate what their big sister did for them.

Primary school teacher Kelly is now 33, and lives in Brentwood with her partner, Mike, a gardener. She says she owes everything to Mel. ‘She basically gave up everything for us at an age when most of us can hardly cope with our own lives. It was such a brave decision, so selfless. My mind reels when I try to imagine any other 17-year-old taking on that challenge.’

Shelley, 31 – who works at a university as a student support officer, and lives with her partner Alex, a communications director – agrees wholeheartedly.

‘I was two when Mum fell ill, and 12 when she died, and those horrible times could’ve so easily scarred me – but thanks to Mel and James, I was given the support I needed to develop a sense of confidence and happiness.’

Three years ago, Mel and James – who now teaches RE at their old school – moved in together, buying the same council house the family had grown up in.

Sadly, around the same time, the girls’ brother passed away from pancreatic cancer aged just 36 – just about the time they’d started to reconnect.

‘I know by the end that he’d loved all his sisters,’ Mel says.

Their father, Terry, had also recently died from leukaemia after a long battle with ill health; likewise, bridges had been rebuilt after so much anger, for so long.

Last year the family came together at Mel and James’s wedding to celebrate everything they’d managed to achieve.

It was an emotional day. ‘My sisters walked me down the aisle,’ says Mel. ‘Their speeches were amazing, saying how much they owed to James and me, but I told everyone there how I couldn’t be prouder of them and their amazing lives with their brilliant jobs and partners.

‘My sisters and I now make a point of meeting up as much as we can – whether it’s just afternoon tea, a pub quiz, or crazy golf. Making happy memories is so important, especially after the hard times we’ve been through.’

However, Mel adds: ‘While I feel so blessed, I just wish it had been easier. I know how kinship carers don’t get the support they need, and there are tens of thousands of families like ours out there who are struggling.

‘I’m writing a book about my experiences, which has been an emotional but important process. Right now, I’m in a happy place – but it’s been a journey.’

Find out more about the Kinship care charity at kinship.org.uk.