I know I speak for a lot of people when I say I wish they would find Madeleine McCann’s remains. I have been following the case closely since 2007 when the three-year-old was abducted from a holiday flat in Praia da Luz, Portugal, sparking one of the biggest missing person cases in history.

Earlier this month, the police were combing the area once again, acting on recent German intelligence. I thought maybe closure was within sight for the poor McCann family who have suffered endless new ‘developments’, mistakes, cover-ups and false accusations.

Indeed, I give full credit to Gerry and Kate McCann for refusing to step away from the glare of publicity but instead to keep the headlines – and with them, an international search – going strong.

Sinking into obscurity is what people in their shoes normally desire, and I can say that with authority because I have been there myself.

My family endured its own awful tragedy when I was 12, also involving an abduction of a child – my sister – a manhunt, police mishaps and the full glare of the world’s media. In our case, there was one crucial difference: we had a body and therefore ‘closure’ (a word I hate).

Helen Kirwan-Taylor was 12 when her older sister Tasha, aged 14, was abducted from her school grounds, in the US capital city of Washington in 1973, and murdered

For 18 hours, however, we lived in the special kind of hell Kate and Gerry have endured for all these years – an unimaginably painful limbo in which, like them, we did not know whether the happy, cherished girl we had seen just hours earlier was alive or dead.

Tasha was 14 when she went missing from the campus of her private school near Washington DC on October 29, 1973.

The day had started normally with both my sisters (Tasha and Tania, 16) being driven to school as usual, but once on the large, leafy school site, Tasha – in a rush because of a lost shoe – grabbed a bicycle to get to chapel faster.

Afterwards, as she rode on the bike to lunch, by the edge of the thick forest which surrounded the school (and frightened many of the other girls, but of course not her), she was abducted by a man called John Gilreath. He was 22 and almost 7ft tall. She was 5ft and weighed just over 6st.

Gilreath was known to the school, having molested two students there before, for which crime he’d been convicted and sent to a psychiatric hospital.

What we didn’t know on October 29 is that he had been released a few weeks earlier without the judge, parole board or headmistress being notified.

This was a high-profile school for the political elite of Washington DC – my father was a diplomat – and had they known Gilreath was out, they might well have locked the girls up and called the police.

What happened next, my brain won’t allow to fade. Having dragged Tasha into the woods, which were a steep fall from the path above, he probably tried to rape her – but she was not having it (there were fingernail and teeth marks all over his arms) so he shut her down with brute force and a small screwdriver.

Numerous puncture wounds were found on her back and lower chest and she had bled profusely. At some point he gave up the fight, tied her to a tree and put a rag in her mouth to stop the screams. We believe she was alive for ten whole hours in a state of half undress in freezing cold and wet autumn conditions, and then darkness.

How long was she conscious? How terrified and helpless she must have felt. How abandoned. I remember Kate McCann’s comment to her mother moments after they realised Maddie was missing. ‘She must be so frightened,’ she said.

No one noticed Tasha’s absence from school classes and it was only when she failed to come home at about 4pm that the alarm was raised and police were called, yet they did not come for ten hours

How exactly does one ‘move on’ from this mental picture? For my father especially, it wasn’t just an imagined method of self-torture, but a reality, because in the end he was the one who found her. When the people who are supposed to keep us safe from undreamt-of terrors fail to do so, the burden for the family grows even heavier.

No one noticed Tasha’s absence from school classes and it was only when she failed to come home at about 4pm that the alarm was raised and police were called. Yet the police did not come for ten hours.

Indeed, they turned up only after my parents pleaded with the Secretary of Defence (my best friend’s father) for help.

Tasha’s body was badly bruised and cut, but the cause of death was exposure. Had the temperature not turned especially cold that same night, had the incompetent police arrived when they were initially called, who knows what might have happened?

By the time the police did start their search, it was already dark and raining and the dogs were unable to follow a scent.

As the night wore on, they called off their search several times because of heavy rain. It was only when my father returned to the campus at 6am the next day with Tasha’s dog Tilly that her body was found.

In fact, it took just minutes for Tilly to locate her body. It was my father who had to untie her from the tree and then somehow call the police to tell them he had done what they should have.

I later learned that in his state of shock he managed to negotiate with the police that the media not be informed until the three of us (I also have a younger brother) were taken to my grandparents’ house, sparing us the onslaught of news vans that showed up on our lawn later that day.

It was an event in my life – and in the lives of many others too – that forever splits time into ‘before’ and ‘after’. In 1973 things like this simply didn’t happen.

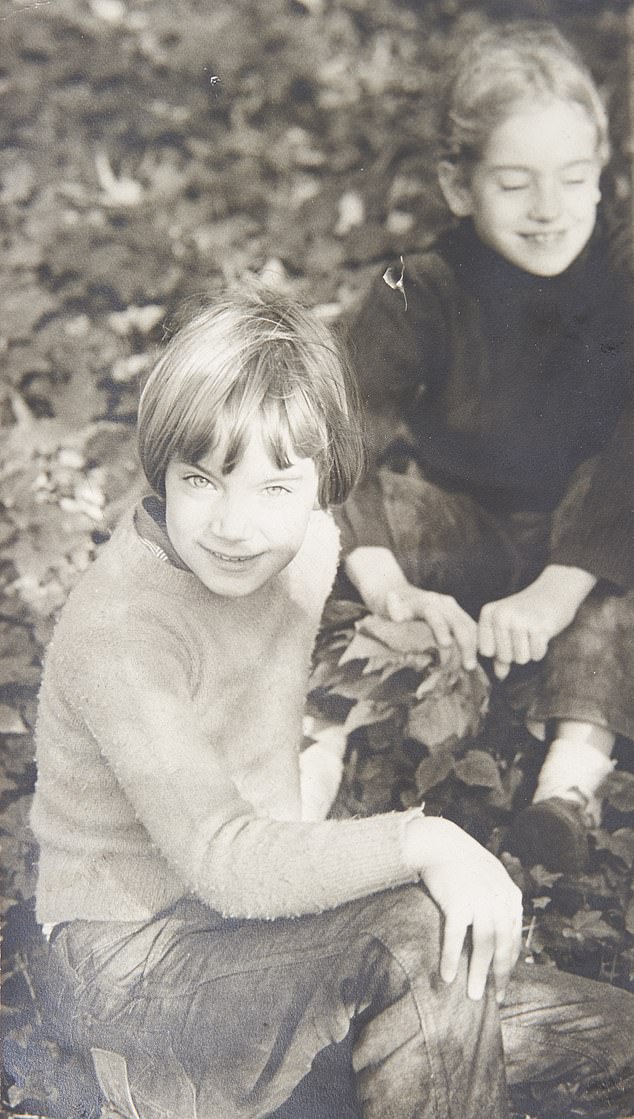

Helen, left, with her mother and sister Tasha

To this day American women come up to me and say they never felt safe again after hearing the endless news bulletins. Yet what quickly emerged was the chilling risk Gilreath had always posed.

It turned out he was a serial offender who’d been charged with eight counts of sexual assault in the past, including on those two other girls at Tasha’s school. He’d been given a 20-year suspended sentence and sent to a psychiatric hospital but – unbelievably – had been discharged to a low-security mental health facility less than a year after his last attack.

With a kind of terrible prescience, one of the victims at Tasha’s school was convinced he would return to ‘get her’ if he was ever let out, and had been repeatedly calling the authorities to check he was still incarcerated.

Purely by chance, one day she got an employee on the phone who told her that he had left the mental health facility.

It turned out that Gilreath had been placed by his doctor in an outpatient programme despite no approval for such a move from the probation office. A further series of bureaucratic errors meant that Gilreath was free to come and go.

And yet when that girl pleaded with the school to do something, she was written off by the adults in charge as hysterical. No one followed it up. No one called the probation office.

I watched the Netflix documentary about the McCanns last night and felt my blood boil as I learned how badly the police bungled the initial investigation and then tried to cover up their mistakes.

The probable culprit, it seems, was under their noses the whole time. In our case, my parents decided not to sue the school (the headmistress was absent the day of Tasha’s disappearance and murder, which didn’t help matters either), but to focus instead on the psychiatrist who deemed Gilreath fit to return to society.

Like Christian Brueckner, the German rapist currently in prison and under suspicion for the abduction of Maddie, Gilreath’s behaviour was that of a textbook psychopath. I have delved into what happened to Tasha many times and each time I learn something new. When she died there was no social media.

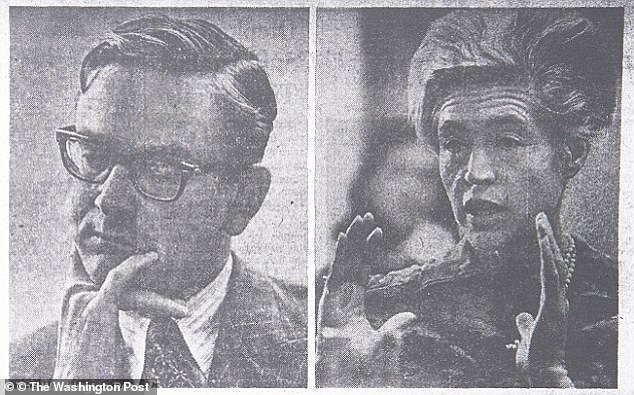

Helen’s parents, diplomat Peter Semler and his Russian interpreter wife Helen Boldyreff

By the time I started investigating, Facebook had arrived, and it was there one day that I received a message from a student who had been to high school with Gilreath. She told me he was known to have tortured animals. He also threw bricks at young women.

As social media progressed, so did my trauma because, eventually, the students in Tasha’s year found me. By going public myself, they felt it was safe to share their stories.

On the night Tasha was abducted, the girls who boarded were left alone in their dorms. There was not a single adult on campus, they told me. And Gilreath, of course, was still at large.

Unlike the school administration, the girls believed the student who warned them that Gilreath had been released and was coming back, and understandably they were petrified. I also discovered they were forbidden to talk about Tasha (the school was worried about a lawsuit). Many now suffer from severe depression, PTSD and suicidal thoughts.

A few years ago, with the help of one of those students, my family managed to put up a bench on the campus with a plaque in Tasha’s memory. It took decades for the school to allow this, scared as they were of their reputation being tarnished. To be fair, the new headmistress is often in touch with us.

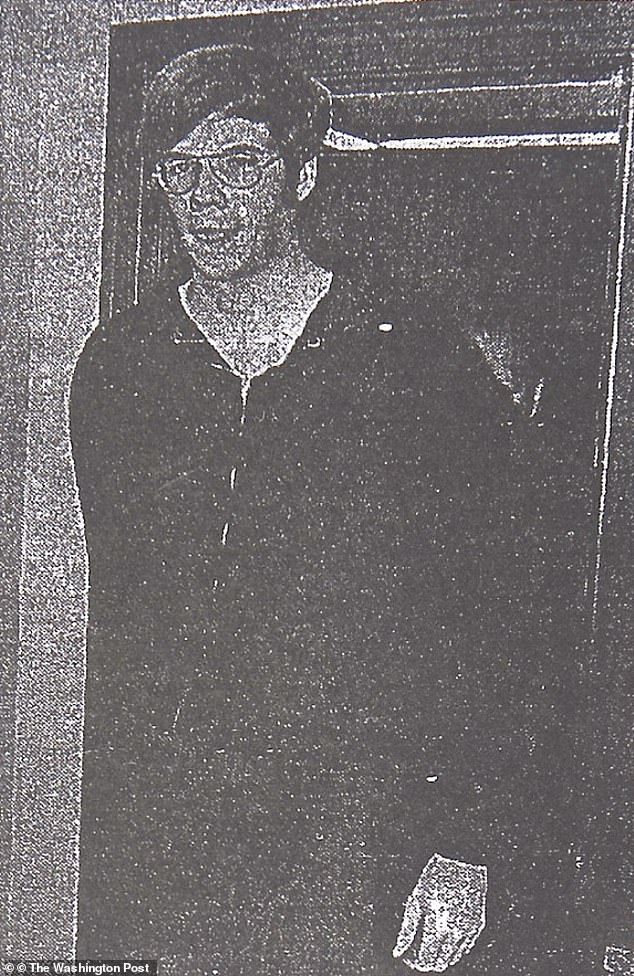

John Gilreath was 22 and almost 7ft tall. He had molested two students at Tasha’s school, for which crime he’d been convicted and sent to a psychiatric hospital, but had been released a few weeks before he murdered Helen’s sister without the school being notified

Unlike us, the McCanns have lived their whole nightmare in the spotlight. I can’t begin to imagine what it would feel like to have total strangers analysing, speculating and criticising my family on social media as they have the McCanns. There are true crime blogs out there discussing Tasha’s murder, but I don’t look at them – what’s the point? It’s a subject that fascinates ghouls.

And yet social media is not an unmitigated evil. Had every girl at Tasha’s school had an iPhone in their pocket in 1973 and tweeted that a student had gone missing (or called their parents), the police would have reacted much sooner. More importantly, we would have reacted sooner.

I know – ‘what ifs’ are fruitless, but that’s how our minds work. We have to make sense of events because the human brain does not like uncertainty.

Like others, I have also wondered why the McCanns, who ate dinner with their friends by the pool the night Maddie was taken, would have deemed it safe to leave their very young children in their rooms alone, but I also understand it.

People who have never experienced trauma do not worry the way I do. They assume things I never could – like everyone will always come home safely and that bad things rarely happen, and that if they do, it’s to other people.

Doctors are some of the most dispassionate people I know: the McCanns would have calculated the risks. What they couldn’t have known was that a known child molester was in the area.

I know that Tasha’s death was a long time ago, but that’s not what my brain thinks. Memories are not stored chronologically but in order of magnitude. So, although the events in the immediate aftermath of Tasha’s death are blurry, the emotions are sharp as icicles.

Helen with Tasha (right). On the night she was abducted, the girls who boarded at her school were left alone in their dorms. There was not a single adult on campus. And Gilreath was still at large. Many now suffer from severe depression, PTSD and suicidal thoughts

Her funeral was the most traumatic day of my life because, in the tradition of the Russian Orthodox church (my mother was Russian), she was placed in an open casket where her bruises were very obviously painted over.

I had never experienced horror before. My mother told me to kiss her goodbye, and this is when I began to heave. I can feel it as I write.

No one knew about trauma then, but how could my parents (who were in a state of abject shock) think we wouldn’t notice the cuts and bruises? We were blissfully unaware of the details at that point, so the shock was profound.

Every time I see a news headline about Maddie, I get a similar kind of jolt. Anyone who has been through a painful ordeal feels emotionally connected to others with similar stories. It’s why we go to support groups, and why they help.

I write about what happened to me when I was 12 as a way of understanding what my body is telling me on a cellular level. We now know for certain that trauma changes the brain and also the immune system.

When I got ill with long Covid four years ago, I knew I was far from recovered from my sister’s death. It doesn’t matter what I think or write or say: what matters is what my nervous system believes.

I am in a permanent state of terrified alertness, especially whenever I can’t find a loved one. Relief comes only when I receive a texted ‘all good’ from them. Then I can finally relax.

I have dabbled for some time with the idea of going to a ‘trauma camp’ – a residential retreat specifically for those who have suffered – but complex trauma like mine is fiendishly hard to treat.

You don’t ‘recover’ from the murder of someone close to you, whatever the flock of Instagram ‘grief influencers’ – selling supplements and subscriptions to their podcasts – tell you. A bit of tapping, chatting or a woo-woo supplement isn’t going to do it.

The McCanns are made of strong stuff, but I know that the bottomless well of grief won’t truly be felt until such as time as they have certainty. Right now, they cling to the tiniest shred of hope. One way or another, I wish them peace.