When David Dalrymple went for a routine dentist appointment, he expected, at most, a ticking off for his inconsistent dental care routine.

At 69, the former miner from Fife was in good health. He rarely ate sugar, had a healthy body weight and enjoyed spending time running around after his eight grandchildren.

David’s only noticeable health problem was his recurring bleeding gums. While he regularly brushed his teeth with an electric toothbrush, David admits he never flossed – a habit experts say is crucial for good oral hygiene.

‘I had some pain when brushing, especially along the gum line – both of which are signs of gum disease,’ he says.

The issue was spotted nearly a decade ago but, despite advice from his dentist on how to improve his brushing, David’s bleeding gums kept returning.

And in April last year, David’s dental appointment was different to usual. After his teeth and gums had been examined, he was asked to take a finger-prick blood test to check his sugar levels.

David was one of the first participants to be signed up for a pioneering trial seeking to catch cases of deadly type 2 diabetes by screening gum disease patients for the chronic condition.

The research project, spearheaded by the University of Birmingham in collaboration with Haleon – the company that manufacturers Corsodyl toothpaste and mouthwash – is based on growing evidence that the exceedingly common dental condition can trigger diabetes.

David had no idea that he was at risk of developing diabetes, putting his sensitive gums down to a lapse in his brushing routine

And, in David’s case, experts say his decision to take part in the study may have saved his life. This is because the test revealed his blood sugar levels were dangerously high.

David was told by his dentist that he was prediabetic – meaning that, left untreated, he would soon develop type 2 diabetes, which raises the risk of serious complications including blindness, loss of limbs and even heart attacks.

‘It was really scary being told that I was at-risk of developing diabetes,’ he says.

‘I was shocked because I don’t eat a lot of sugar. I wouldn’t have known if it wasn’t for this test.’

David is far from alone. More than half of British adults either have gum disease or are at-risk of developing it.

And experts say these patients could be in danger of developing diabetes.

Yet, unlike David, the vast majority are not being tested for the life-threatening condition.

Experts add that this is concerning because, once identified, gum disease is easily treated – a move which could also slash the risk of diabetes.

Gum disease is thought to affect about four in ten people and this could lead to diabetes

Join the debate

Should dental care be free for all, or is it fair to expect people to pay for private treatment?

‘Severe gum disease and type 2 diabetes are unequivocally associated with each other,’ says Professor Iain Chapple, an expert in periodontology and a co-author of the research.

‘But the good news is that if you treat gum disease in people with diabetes well, blood sugar control improves significantly, complication of diabetes reduce and overall health outcomes improve.’

So, why does gum disease cause diabetes? And how can it be prevented?

Gum disease typically presents in the first instance as sore, bleeding gums.

Bleeding often occurs after brushing, flossing or biting into hard foods such as apples. It can also lead to bad breath, shrinking gums and loose teeth.

It’s typically caused by poor oral hygiene which allows plaque – a sticky film of bacteria – to build up on the teeth and harden.

In recent years, the number of Britons living with the condition has surged as it has become harder for patients to see NHS dentists. Dentists are in a long-running pay dispute with the Government.

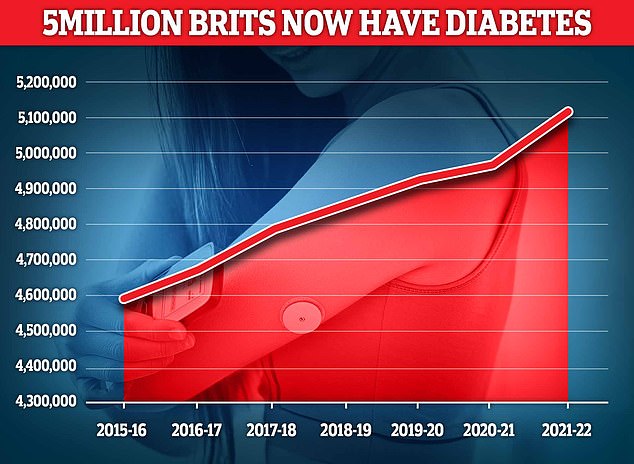

Now experts say a lack of health service dental care could be driving up cases of type 2 diabetes, which affects more than 5million Britons.

Experts say a lack of health service dental care could be driving up cases of diabetes

Experts say it was previously thought that diabetes itself raised the risk of gum disease. This is because the condition interferes with the immune system’s ability to fight bacteria.

But more recent research seems to show that the relationship between the conditions is two-way.

‘For a long time, we thought of diabetes purely as the driver of gum disease,’ says Dr Seb Lomas, a biological dentist. ‘We now understand that the relationship goes both ways’.

Experts explain that the presence of bacteria in the gums also causes blood sugar to go up to provide the immune system with energy to battle the invaders.

In short bursts, these blood sugar spikes are harmless. But, over a long period, research suggests this can trigger diabetes.

Studies show that patients with gum disease are more than 25 per cent more likely to develop diabetes, compared to those with healthy gums.

Research, published by the Economist Impact Health Inclusivity Index, supported by Haleon, found that tackling gum disease could prevent more than 300,000 cases of type 2 diabetes over the next decade.

Experts say there are a number steps to effectively treat gum disease.

If the condition is in its early stages, a dentist might recommend better teeth brushing techniques or advise that the patient sees a hygienist who can clean the teeth. This would normally cost around £80 at a private hygienist.

If the gum disease is more serious, then antibiotics, gum surgery and even tooth removal may be necessary.

Experts say the best way to reduce the risk of gum disease is to brush twice a day using a fluoride toothpaste, as well as using an interdental brush or floss to clean between the teeth.

These measures did the job for David Dalrymple.

His dentist was able to treat his gum disease by cleaning under the gums and instructing him to use interdental brushes daily – focusing his brushing routine on his gums.

Six months later, he saw his dentist again for a check-up and received another blood test.

Not only had his gum disease markedly improved, but his blood sugar levels had also significantly dropped – meaning he was no longer prediabetic.

‘I was over the moon,’ he says. ‘But if it hadn’t been for my dentist, I never would have known that I was at risk of developing diabetes. And my doctor wouldn’t have known either.’