Looking back, Brexit truly marked the beginning of the end of my marriage to Michael Gove. Politics had infected every aspect of our lives – and it caused untold damage.

Our close-knit group of friends – many stretching back to university days – were slowly but surely pulled apart. Godparents were at war with each other, children who had grown up in each other’s houses were suddenly on non-speakers as the adults took sides.

So much of my life – my identity – had been built on these relationships and now the whole landscape of my existence was fracturing.

I’d been perfectly prepared to accept that some of my friends felt very strongly that leaving the EU would be a big mistake. What I failed to appreciate was that they could not – or would not – separate that political opinion from their friendship with us.

Pressure from the Camerons played no small part in this: I was told in no uncertain terms that the order had gone out to send us both to social Siberia. Within the space of a few days almost my entire friendship group unravelled. Messages went unanswered, calls not returned, emails ignored.

Of all our BB (Before Brexit) friends and acquaintances, George Osborne and his now ex-wife Frances had remained the most neutral throughout the campaign.

He’d always tried to separate the personal from the political and behaved like a consummate grown-up whenever we saw him socially.

For her part, Frances was one of the first people to text me to see if I was all right on that momentous Friday morning – which, given the circumstances, meant a great deal.

Later they had their own domestic dramas, as their marriage collapsed and George behaved quite abominably towards Frances, but she and I are still close friends.

Sarah Vine and her then husband Michael Gove leaving the 2016 wedding reception for Rupert Murdoch and Jerry Hall

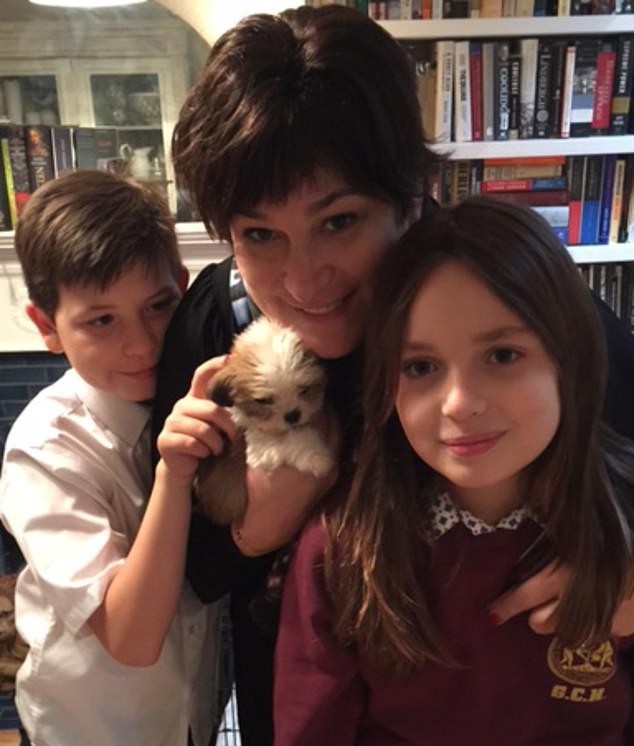

After the referendum in 2016, Sarah was concerned for the safety of children Bea and Will

On the day the Gove/Vine family moved out of their Notting Hill home in the summer of 2017, a chill entered their marriage

It was the week that followed the Brexit vote which decided Michael’s political fate and, in the end, twisted the knife into our marriage. Michael was jittery, febrile and, quite frankly, a bit bonkers that first weekend.

It turned out that on the Friday, after Dave Cameron resigned as Prime Minister, Michael muttered to Boris Johnson that he was ‘minded’ to support him for the leadership. It was one of those little-thought-out throwaway remarks that would come back to haunt my hapless husband.

That Saturday, Michael called George Osborne to tell him he had to get behind Boris, that Michael had seen how much he’d changed, how hard he’d worked on the Leave campaign, how he was bound to want George in his team.

But it turned out that even George had his red line. ‘Anyone but Boris’ was, Michael told me much later, George’s basic line in these conversations.

What I was surprised hadn’t happened was that Michael and George hadn’t, at any stage, considered that the two of them together might be the magic ticket.

I think George’s distrust of Boris must have played on Michael’s mind an awful lot, possibly because part of him shared it, too.

Michael had huge respect for George – in many ways he was something of a mentor to him, politically. And Michael had always seen the flaws in Boris, often up close.

So when it turned out that, post-vote, post-Dave’s resignation, post-everything, while Michael and his team were tearing their hair out over what to do, Boris had spent half the weekend playing cricket against Earl Spencer’s Althorp team in the grounds of the Spencer family’s ancestral home, I had a real sense of foreboding.

Partly for this reason, I stayed behind when Michael went over to Boris’s house near Oxford on the Sunday for their Project of War; that, and the fact that our two children needed some parent time.

It was a gorgeous day and when the two-car convoy of Michael, two special advisers (Spads) and his parliamentary adviser, loaded to the gunwales with laptops, tablets, spreadsheets and policy papers, turned up to Boris’s house, they found his advisers sitting around barbecuing sausages, knocking back the rosé and generally having a jolly old Sunday with the boss.

‘There was such a contrast of styles between the two teams,’ said Michael later, ‘with my guys all action stations and stats and schedules while the rest just partied on and I did wonder why Boris wasn’t saying to his team: ‘C’mon chaps, we’ve got work to do.’ It was all just too lackadaisical. A tiny worm of doubt entered my mind.’

What was worse, fattening up that worm of doubt, was that Boris pulled Michael aside that afternoon and meandered through an explanation about how, despite them both assuming that Michael would run his leadership campaign, that, er, actually, he may have offered that job to Ben Wallace as well.

‘He’s a great guy, though,’ Boris apparently enthused, ‘so you can do it together – that will be fine, yah?’ Michael was livid. But it got even worse.

I don’t know Andrea Leadsom and have nothing against her, so I’m not 100 per cent sure why she effectively became the touch-paper by which Michael set fire to the Boris leadership campaign and thereby, eventually, to our lives together.

The entire Leave team, including Michael and Dom Cummings, had apparently discussed with Boris at some length how he was not, repeat not, to make any firm offers of ministerial roles in his putative Cabinet: that this would be jumping the gun at best, and a crazy hostage to fortune at worst.

So, when Andrea Leadsom told Boris and Michael that she wouldn’t stand and would support him if he gave her either the job of Chancellor or chief Brexit negotiator, Michael gave Boris a warning shake of his head and mouthed at him not to say anything. To no avail. ‘No, no, sorry, Andrea,’ said Boris blithely, ‘Gover’s going to be Chancellor and the negotiator.’ Cue fury from Leadsom.

Michael said later that he could have throttled him but satisfied himself with suggesting to Boris, through gritted teeth, that the only way out of this and to keep her support was to handwrite a letter to Andrea, asking her to keep schtum and hinting that the Brexit negotiator job would be hers afterwards.

How the tone-deaf Leadsom had thought herself a contender for these top jobs, having held only two rather junior ministerial roles herself, is beyond me, but it was clear she needed to have this letter.

That Sunday night, the chat around our kitchen table veered from the whirling world stage to the grubby trading of favours and the sycophancy surrounding the incoming Court of Johnson.

Numerous news outlets portrayed Sarah as a ‘malign, manipulative force, puppeteering behind the scenes and controlling my poor put-upon husband’s political decisions’

It was the week that followed the Brexit vote which decided Mr Gove’s political fate and, in the end, ‘twisted the knife into our marriage. Michael was jittery and febrile’

I think better when I’ve written things down so, before Michael was up that Monday, I wrote an email to him that clarified my thoughts. In the email, I tried to summarise what we’d all discussed the night before; the need to pin Boris down about what he’d offered Michael, to get guarantees to ensure that no one else was being fobbed off with the same offers.

I was simply encapsulating what we’d all been discussing the night before, like a secretary sending out the minutes of a meeting.

I CC-ed those who’d been there, pressed send, snapped the laptop shut and rushed to work. Except that instead of one of Michael’s two Spads called Henry, I’d accidentally CC-ed another Henry, some random PR I had in my contacts.

In this case, PR Henry was still recovering from caning it at Glastonbury so it took him a day to open it. At which point he momentarily stopped writing about lipsticks, shimmied out of his budgie-smugglers and decided to leak the email to the papers. I do hope he was paid enough to upgrade from a tent to a Glasto campervan the following year.

To me there was nothing wild about this email. It was dealing with the Boris we all knew: all fire and flash, foibles and flaws, and it was simply the type of bolstering, hold-your-nerve billet-doux that any wife would send their jittery husband.

But the leak prompted a media frenzy, with numerous outlets portraying me as a malign, manipulative force, puppeteering behind the scenes and controlling my poor put-upon husband’s political decisions.

The Telegraph questioned whether I was ‘a latter-day Lady Macbeth, secretly directing the fate of the Tory party with her ‘poison pen’.’

Seriously? A husband offering his wife advice is seen as kind and insightful; but me offering Michael the benefit of my journalistic acumen and my wifely support was Lady Macbeth? Oh, would you ever all just f*** off ?!

The furore upset me because the whole Lady Macbeth thing is such a lazy, sexist trope. It’s the one thing I actually have rather a bit of sympathy for Meghan Markle over: this idea that, somehow, it’s all her fault that Prince Harry turned out to be such a spoilt, vindictive little brat.

Why, because he couldn’t manage that all by himself? Michael appeared to think it was all quite funny, but it contributed to the general spiral of lunacy that week. Our son remembers it well.

‘I am mad!’ I remember Dad saying in the bathroom one morning,’ says Will now. ‘We were both brushing our teeth and he was gurning at himself in the mirror: ‘I’m going mad!’ he’d say, with a wild look in his eye.’

Then came a light but fatal blow. I’d forgotten about Andrea Leadsom until Michael arrived home on, I think, the Wednesday of that fateful week. He was spitting nails. ‘One job,’ he kept saying, pacing up and down the kitchen. ‘One bloody job.’

It turned out, of course, that Boris hadn’t sent the letter. The outcome was all too clear: Leadsom was still very much the thorn in their side. I called in back-up in the form of Michael’s two Spads. They arrived and tried to calm him down but he shrugged them off and rang Dom Cummings.

Dom later denied he was specifically consulted (and even had the nerve to present himself later as a critic of Michael’s change of heart).

But he was on speakerphone and we all heard his response to Michael’s gibbered reiterations about how he was done with Boris’s hopelessness and incompetence, how he couldn’t trust him to step up to the mark.

‘This is just how I feel,’ he concluded rather forlornly. ‘Well, in that case,’ said Dom, ‘you should do your own thing.’

Looking back, that was a key moment. Michael trusted Dom’s judgment implicitly. His approval meant a lot, maybe everything. If Dom had argued against, I’m pretty sure Michael would have shelved his misgivings.

That night Michael didn’t sleep at all, having instead what he described to a friend who came to supper the night after as a ‘long, dark night of the soul’. ‘I gazed into the abyss,’ he told her, ‘and thought: ‘This man cannot be trusted to run the country. He has neither the focus nor the elan. Nor is he actually competent enough.’

And then I shook with fright, literally sweated with terror, at the thought that I was helping to put him into that position. And I knew I couldn’t do that.’

Michael had repeatedly told the nation that he’d never run for leadership. But if he was to take Boris down, what else could he do? Boris was a speeding train and Michael felt he had no choice but to hurl himself onto the tracks to derail the disaster that would inevitably follow if he didn’t.

What happened next, we all know. Michael called a press conference saying he could no longer support Boris and announced his own bid for the leadership.

A ‘betrayed’ Boris announced he wouldn’t be standing. With the nation’s outrage at ‘throwing Boris under the bus’ ringing in his ears, Michael pushed on, but the damage was done: the prevailing narrative was that he’d plotted the whole fiasco for his own nefarious ends – almost certainly egged on by his villainous, ambitious witch of a wife.

Cue thunder and lightning, very, very frightening.

Mr Gove felt he could not support Boris Johnson in the Tory leadership campaign. He said: ‘This man cannot be trusted to run the country’

After the June 2017 snap election and a year after firing him, Prime Minister Theresa May realised she was losing her base support and invited Mr Gove back in from the cold

Again: seriously? As if anyone would have plotted this farce. Michael didn’t want the job; he knew everything about the timing was off, that this wasn’t his moment and even had a twinge of fear that he might be in the final two. He just didn’t want Boris in the job.

I also wonder to this day if there hadn’t been a thread of hope in Michael’s mind that George might have crossed back over if Boris went – and brought the ex-Cameroon cavalry with him.

Perhaps subconsciously that was part of why he did it. But this never happened, the mud clung to Michael and, in the end, the leadership contest was both swift and sure, with the gimlet-eyed Theresa May the winner.

To be honest, a big part of me was relieved. May was utterly graceless in victory. She dispatched Michael with truly impressive brutality, almost wagging her finger at him and refusing to let him speak in their final meeting, in her tiny parliamentary office. It ended with her telling him to go away and have a think about loyalty.

‘I felt like a delinquent schoolboy,’ he told a friend afterwards. ‘So I simply said, ‘As you wish, Prime Minister,’ and left. When I walked back to my departmental office, I arrived to find that she had sent in the heavies even before she saw me, that they were already there packing up all the computers, to the shock and horror of the Spads.’

Classy, Mrs May, real classy.

In the immediate aftermath, we fled to the Lot-et-Garonne in south-west France for a holiday, to hide and lick our wounds. I’ve never been so tired and would fall asleep at every opportunity.

For his part, Michael took refuge in another room, listening to endless murder mystery books on tape – wallowing in the golden haze of Lord Peter Wimsey and Dorothy L. Sayers.

We’d been banished from the Court of Cameron for good, cut off from so many of our political friends, and Michael had been fired by Prime Minister May and was generally in the dog house.

As we sat under those dark, star-lit skies at night, we were both too numb and stunned to talk about what had happened, or think about what to do next.

Afterwards, Michael started writing for The Times. I secretly – and fervently – hoped that he’d forget the siren call of frontline politics, that the man I’d married would slowly begin to emerge from his carapace, stripping off those layers of political camouflage to emerge the same goofy, incorrigible genius he was when we first met.

For my part, I had my own recovery project. I loved our home in Barlby Road, North Kensington, but felt strongly that we needed to move. The children were beginning to be gangly teenagers and we lived in an area rife with gang pressures, prostitution and drug deals.

Then our son Will was mugged on the way back from school – the standard West London heist of his phone, grabbed by a kid on the back of a scooter – and that shook me.

I already felt unsafe there post-referendum: everyone knew exactly where we lived. I felt we were all marked property and could be singled out at any time, sworn at on the bus, or worse.

To my surprise and despair, Michael was dead set against us moving. I couldn’t for the life of me understand why.

Sam and Dave still lived around the corner from Barlby Road; Boris’s sister Rachel lived just off Ladbroke Grove, Dave’s ex-gatekeeper Kate Fall, too.

All these people now hated us, as they never seemed to stop reminding anyone and everyone. I just didn’t want to be around that any more, forever worrying about bumping into them, everything a sad reminder of happier times.

Michael felt differently: Barlby Road was still, despite everything, his happy place. He wanted to stand still and take stock; I wanted to run for the hills. But even he, I think, could see the advantages of a bigger space with growing teenagers – and so eventually, reluctantly, he acquiesced.

On the day we moved, in the summer of 2017, a chill entered our marriage.

When I say that the first removals pantechnicon was loaded to the gunwales with Michael’s books, I’m only slightly exaggerating: there was only room for our bed, which the removal men duly unpacked and assembled.

It was going to be a busy day: we had four floors of a new house over which to distribute all our stuff: there were a lot of tiny decisions to be made.

My mother had flown over from her home in Italy to help. I was gobsmacked when, the removal men having put together the bed in our new bedroom, Michael opened up his briefcase, removed a couple of books, kicked off his shoes and repaired to his side of the bed to read them.

The second lorry arrived and he moved not a muscle. He certainly didn’t unpack anything. Mum and I did everything – and I do mean everything. I was incredibly upset.

Mr Gove with Boris Johnson on the winning night of the General Election in 2019, the same year Sarah moved out of the master bedroom and into the little box room at the top of the house

Part of me wanted to rip his head off: how dare he not help me? What sort of lazy, selfish so-and-so could have lain there all day and simply ignored all the ruckus around him?

Later, I did my best to make the first night in our new home super-special, raising a glass to our new life.

But the rage inside me continued to fester. I remember I hunted for days and days on eBay to find enough bookcases to house Michael’s books. Once they had arrived, I asked him to unpack the book boxes – there were at least 100 – but he simply refused. I kept asking and asking, and eventually he did, but stuffing the books in any which way.

‘I knew you could sense that I wasn’t OK with the whole ‘new house, new life’ idea,’ Michael says, when I remind him of this day. ‘I know I was reluctant and mulish, dragging my heels. I just hate admin and change.’

Gradually, this sense seemed to seep into other areas of family life. Michael was always a firm believer in the importance of a to-do list, and it dawned on me that if the kids and I featured on his at all, we were a fair way towards the bottom.

Suddenly I’d become a bookkeeper of marital annoyances; noticed all the times he simply checked out of family life; noted the disproportionate levels of attention we gave our now tricky teenage children: he not enough, me too much by way of compensation; began to subconsciously log the amount of time he spent out in the evenings; couldn’t help but be painfully aware of how little we were talking.

I reasoned he was probably just a bit depressed as a result of everything (I mean, who wouldn’t be?) and tried my best to make him feel loved and appreciated. But it seemed as though not even my best efforts could make him care about anything but his one true passion: politics.

After the June 2017 snap election, when Prime Minister May realised she was losing her base support, she invited Michael back in from the cold, offering him a Cabinet position as Environment Secretary.

Even though the naive part of me was secretly still amazed that, just like that, he could shrug off the memory of his last humiliating meeting with May and scamper back to Whitehall like a puppy, I could see how happy he was to be working on a complicated brief again.

It was around this time that the notion began to dawn on me that perhaps Michael and I no longer wanted the same things in life. I kept going, of course, but from then on, I just felt like I was running out of rope to hold my marriage together. He just seemed so much happier elsewhere.

I, too, found other things to occupy my time, throwing myself into work and children and spending more time with my parents.

Our daughter Bea was having a tough time at school. When she was in Year 9, in 2017, she tells me now, there was a bust-up between her and some other kids during Pride Week, during which Michael’s name came up as ‘not just an effing Tory but effing gay’.

Meanwhile, our new home became less of a haven when the security services told us that someone had painted our home address on a wall in Derry, in Northern Ireland. Then for Beatrice’s 18th, she received a card, postmarked Northern Ireland, with her name and address in multicoloured childish writing.

Excitedly, she opened it. Inside was a card that read ’18 today! Yay!’ with a badge attached saying ’18, Woo!’ And inside that, in letters cut out from a magazine or newspaper, the following message: ‘Tell your dad that if he doesn’t [and here I won’t specify what he had to do, for security reasons] he won’t live to see you turn 19. Do not make this public.’

That will always be my abiding memory of her 18th. But we were lucky. Much later, in 2021, when David Amess, the MP for Southend West was murdered in a horrific attack by an Islamist extremist, Ali Harbi Ali, our names came up in the police investigation that followed.

Analysis of Ali’s phone records showed that he’d been standing in our road for hours each day for a full week before he shifted his focus to Amess. He’d tailed Michael on two of his morning jogs and his phone signal showed he’d clearly followed me to work at the Daily Mail.

I shudder to think how close we came to being his prey – and simultaneously feel guilty that the Amess family had to suffer such grief and loss themselves instead.

If I’d thought post-Brexit that the game was probably not worth the candle, by now I was utterly convinced. When Michael went for the top job again in June 2019, running for leadership directly against Boris this time, I was well and truly done.

I really couldn’t give a toss about his success or failure, to be brutally honest.

Boris romped it and Michael was – yet again – called back into government, this time as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (effectively deputy prime minister); he and Boris duly got Brexit done with the compromised January 2020 Withdrawal Agreement. The question, by now, was what did I want to be, where did I want to be? Did I even, when all was said and done, want to be a wife?

During 2019, I’d moved out of our bedroom and into the little box room at the top of the house. Nothing was said. The children hardly commented. I felt so detached from reality by now that I didn’t even wonder at that.

In July 2021, Michael and I announced that we were separating, and by January 2022 we were divorced. When we finally talked to the children about the split, they seemed unnervingly unsurprised.

‘You never fought,’ says Bea now. ‘The divorce was very, very calm – to be honest, you were kinda divorced for years.’

There was no scandal; our marriage had simply been gently eroded away.

- Adapted from How Not To Be A Political Wife by Sarah Vine (HarperCollins, £20), to be published June 19. © Sarah Vine 2025. To order a copy for £18 (offer valid to 14/06/25; UK P&P free on orders over £25) go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.