Recent weeks have given Venezuelans at home and abroad new reasons to hope authoritarianism in their country might soon be on its way out.

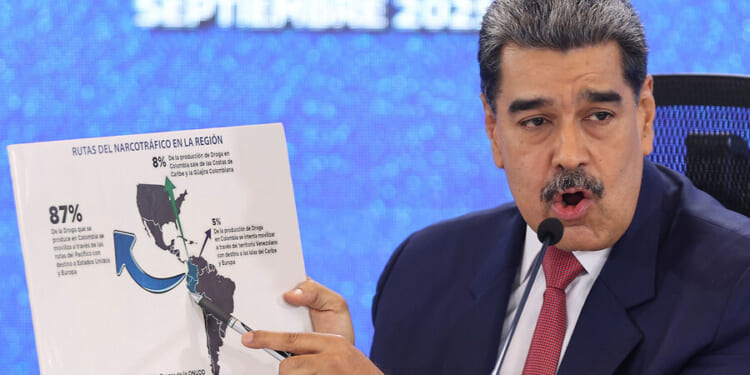

The announcement this month that María Corina Machado had won the Nobel Peace Prize has fortified those who, like her, have fought to restore democracy in Venezuela. Meanwhile, the United States’ new military campaign against drug trafficking has raised the prospect of toppling President Nicolás Maduro. Some 86% of Venezuelans support the U.S. actions, according to a survey by DC Consultores.

But those closest to the work of liberating Venezuela from the Maduro regime paint a more complicated picture. All are grateful for the new attention, and some see military action as a crucial lever. Others worry about the consequences of foreign involvement. Looming behind everything are what appear to be intensifying efforts to target Venezuelan opposition figures who have sought refuge abroad.

Why We Wrote This

Many Venezuelans support U.S. military strikes against drug trafficking, hoping they could topple President Nicolás Maduro. But the challenges facing those seeking to reestablish democracy in Venezuela go much deeper.

There is cautious optimism, but also a wary sense that the need for vigilance is only growing.

This is “the beginning of a new stage of transnational repression against critics of the government,” says Rafael Uzcátegui, a Venezuelan human rights defender who has fled to Mexico City.

U.S. pressure on Maduro

U.S. President Donald Trump has heaped pressure on the Venezuelan government, sending about 10,000 troops and eight major warships to the Caribbean. These forces have destroyed at least seven vessels suspected of drug trafficking in the region, killing at least 32 since Sept. 2. Last week, Mr. Trump confirmed that he has authorized Central Intelligence Agency operations within Venezuela. (On Wednesday, it was reported that the administration had carried out an additional strike against a suspected drug boat, this time off the Pacific coast of Colombia. At least two people were believed killed.)

These actions could “change the current equilibrium” and lead to the fall of Mr. Maduro’s authoritarian government, says Jose Morales-Arilla, a professor at Tecnológico de Monterrey in Mexico.

Many Venezuelans see a degree of hope in Mr. Trump because, like Venezuela’s authoritarian leadership, “he also doesn’t blink,” adds Dr. Morales-Arilla. The fact that Mr. Trump was willing to bomb Iran in June, he says, sends a strong signal about how far he might be willing to go.

Some Venezuelans think that commitment to force is key. “Venezuelans have tried every imaginable political strategy – from negotiation, to street protests, to massive participation in elections – despite having everything stacked against them,” says Mr. Uzcátegui. He adds that many Venezuelans now see the use of force as the only option.

But military threats raise questions for others, especially given the U.S. history of interference in Latin America. “We’re worried this is in the hands of foreign governments,” says Ligia Bolívar, general coordinator at Alerta Venezuela, a human rights organization.

For their part, opposition members both within Venezuela and abroad try to continue carrying out their work.

Rising threats to the opposition

Sitting in a Venezuelan restaurant in Bogotá, Colombia, a member of the Venezuelan opposition’s campaign team says it is important “to manage expectation and hope in a responsible manner.” He is convinced Venezuela will eventually be free and democratic, but he remains unsure when that day will come. He had to flee after last year’s widely disputed presidential elections, and now he sees new threats.

On Oct. 13, three men fired more than a dozen shots at two Venezuelan opposition supporters in Bogotá. It sent shock waves through the community of nearly 3 million Venezuelans who have sought refuge in Colombia.

To stay safe, the opposition campaigner regularly changes his routines and rarely tells anyone where he lives. He also asked that his name not be shared for this story. “It brings back all the memories … the persecution, the threats, the security concerns that we had in Venezuela, they are brought back to life when you thought you had left them behind,” he says.

Venezuelans in Colombia “feel a lot more vulnerable than before,” and some are considering leaving the country, adds Ms. Bolívar.

Such threats have been building. Last year, the body of a former army lieutenant who defected from Mr. Maduro’s government was discovered in Chile buried in a suitcase under a slab of cement. Two days after this month’s attack in Bogotá, leaders of a nonprofit helping Venezuelan migrants in Colombia reported threats and intimidation. Gaby Andréina Arellano, president of the nonprofit, says the events “have triggered a full state of alert.”

Despite difficulties, opposition supporters say they believe things improve when the world pays attention. Recent threats and attacks against Venezuelans in Bogotá “have generated fear and anxiety,” but “the foundation has not closed its doors,” says Ms. Arellano.

Mr. Uzcátegui warns that the day Venezuela stops being international news and human rights organizations look away, “the Venezuelan authorities will feel even more free to commit abuses of power.”

“The goal has been the same in the last 25 years,” the opposition campaigner insists, “to achieve a legitimate, peaceful, and democratic transition in Venezuela.”