Ever since America’s founders decided that the best way to prevent tyranny was to diffuse power across branches of government, those branches of government have competed for authority. Presidents have wrestled with Congress, for example. The federal government has clashed with state governments.

This year that power struggle has been between President Donald Trump and the federal judiciary.

His administration has sought to expand presidential control in numerous ways, including firing tens of thousands of government employees, enacting sweeping tariffs, and expanding immigration enforcement powers.

Why We Wrote This

A slew of lawsuits has resulted from the Trump administration’s expansive use of executive orders. Courts are hearing hundreds of cases as a result. Here’s an overview of where courts are restraining or approving of the president’s actions.

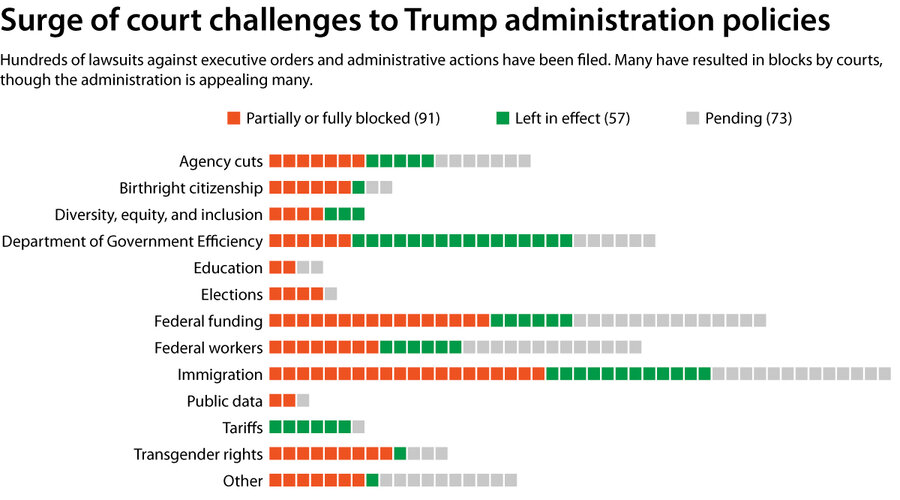

Courts have responded by blocking many of these efforts, saying they are unlawful. Courts are hearing hundreds of active cases involving the Trump administration; as of June 13, there have been at least 187 rulings temporarily pausing administration policies, according to The New York Times.

Mr. Trump has criticized these rulings, as well as the judges – often appointed by Democratic presidents – who issued them. But the Trump administration has also been enjoying more success in the upper levels of federal court.

The broad narrative has been that the Trump administration is losing heavily in the courts. The reality is more complicated.

Some specific cases illustrate this complexity.

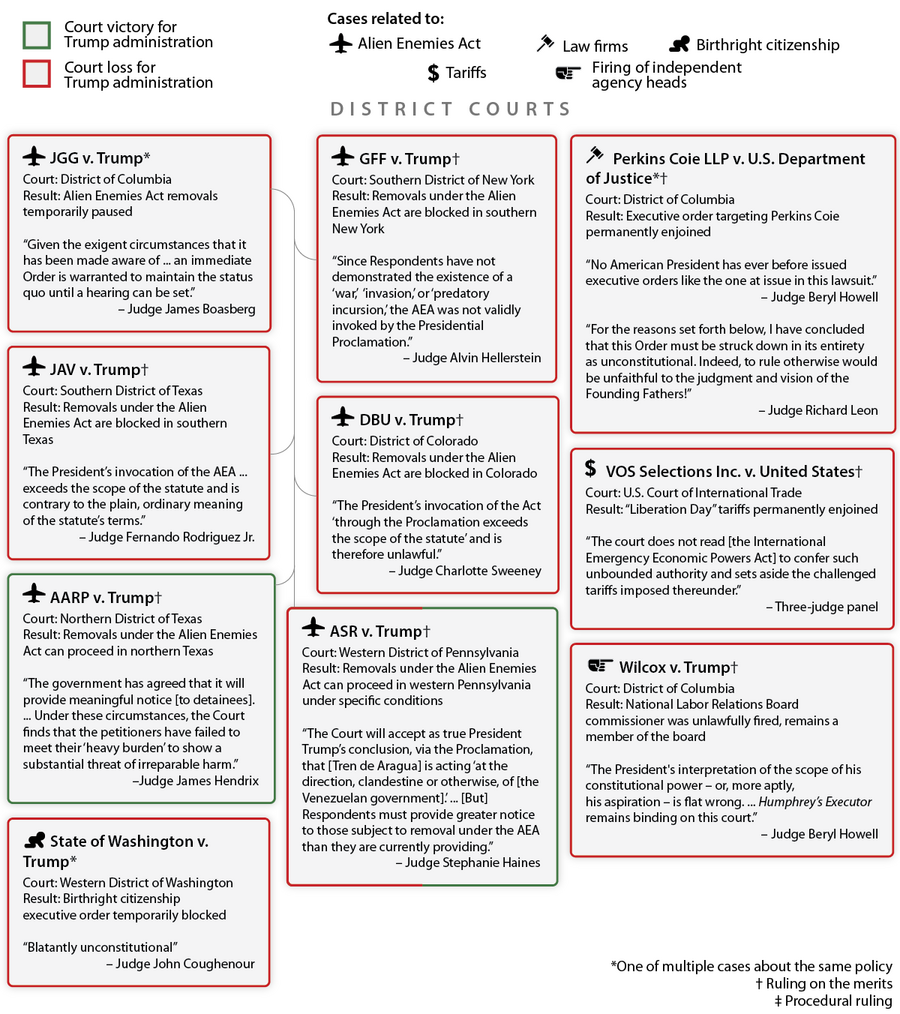

In one group of cases, parties are challenging Mr. Trump’s executive order redefining birthright citizenship. Another ever-growing series of cases challenges his invocation of the Alien Enemies Act to rapidly deport alleged members of Tren de Aragua, a Venezuelan gang, with minimal due process. Other lawsuits challenge his firing of Gwynne Wilcox, a chair of the National Labor Relations Board (Wilcox v. Trump); his use of an emergency powers law to enact sweeping tariffs (VOS Selections Inc.); and his executive orders punishing law firms (Perkins Coie LLP v. U.S. Department of Justice).

District courts

District courts are required to obey the precedent of the U.S. Supreme Court and the appeals court circuit in which they’re located. If a judge thinks a policy is probably illegal, they can issue a temporary order, or a nationwide injunction, preserving the status quo until the case is resolved.

Precedent has been the justification for several Trump administration court losses. A lot of the litigation concerning Trump policies has focused on the legality of these temporary orders, including whether a single judge can issue a nationwide injunction that affects the entire country.

Trump officials claim that their administration has been disproportionately targeted, particularly by nationwide injunctions. Federal courts issued 25 such injunctions in the administration’s first 100 days, compared with 28 during the entire Biden administration, according to the Congressional Research Service. Critics counter that Mr. Trump has issued far more executive actions than other presidents: 161 so far, compared with 162 during President Joe Biden’s entire term, according to the Federal Register.

Appeals courts

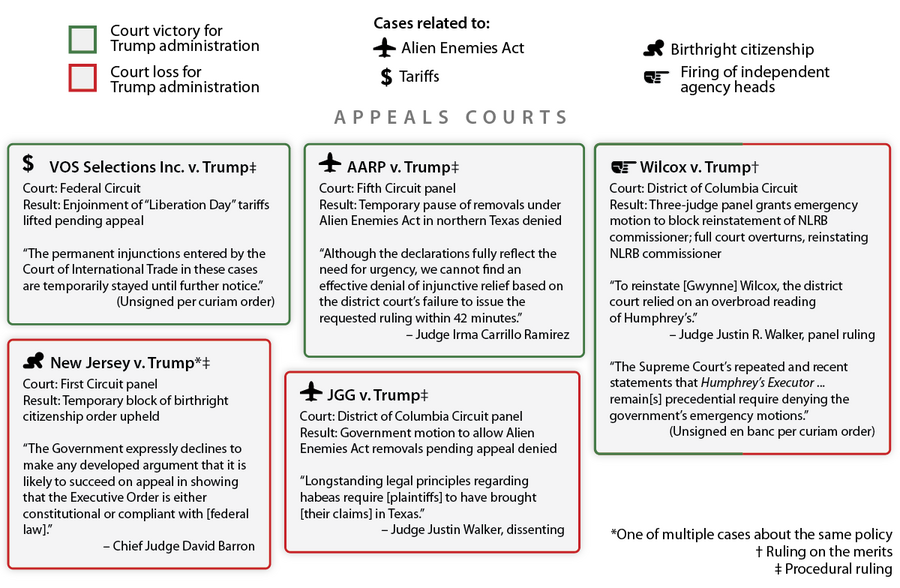

So far, the government has enjoyed more success in appeals courts than in district courts, but that success has been limited. Appeals courts are also bound by Supreme Court precedent, such as Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, a precedent at issue in the Wilcox case, which established that Congress can limit the president’s ability to remove without cause heads of certain independent federal agencies.

Unlike district courts, however, appeals courts have multiple members. An appeal is usually heard first by a three-judge panel. Panels are meant to help manage caseloads, and to let multiple sets of eyes – and opinions – review a case. A decision by a panel can be reviewed by the full appeals court, a process known as en banc review.

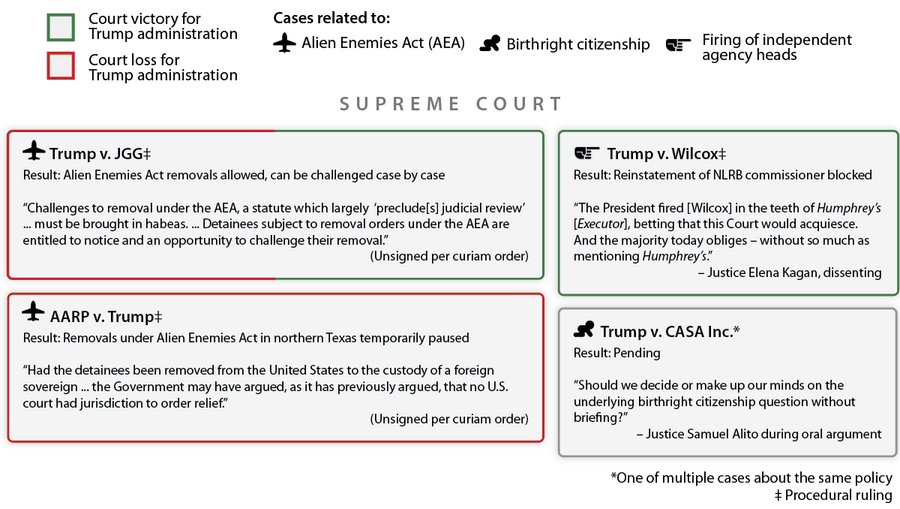

The Supreme Court

The Trump administration has not been shy in asking the Supreme Court to review lower-court decisions against it. The court has received 19 requests for emergency relief from the administration, as many as the Biden administration sought in four years, according to Steve Vladeck, a Georgetown Law professor who tracks the emergency docket.

For the most part, the administration has found a sympathetic ear, though that sympathy has often been qualified.

At times the court has plainly ruled in the administration’s favor, such as lifting a lower-court order that Ms. Wilcox must be reinstated. But the justices also said Alien Enemies Act deportations can proceed, but only under specific conditions. The high court is reviewing the birthright citizenship case, but with a focus on a procedural question, not the merits of Mr. Trump’s order, which lower courts have found to be unconstitutional.

Because so many of the Trump-related lawsuits have become about challenges to temporary district-court orders, courts have not yet examined the merits (i.e., the core legal questions) of many cases.

Answers to those questions will begin arriving soon, however. Some cases are now lined up for the Supreme Court to rule on the merits as soon as next year, including the Wilcox and tariffs cases. Other cases are still percolating in lower courts.

Even cases the Supreme Court has already ruled on could return. Alien Enemies Act deportations are being challenged in federal courts around the country and could soon return to the justices. While the high court has yet to issue a ruling in the birthright citizenship case argued earlier this year, a case confronting the core legal issue may arise in the future.

Mr. Trump’s wranglings with the courts, in other words, are far from over.