Are you dreading going back to work after the festive break? Do you worry about burnout, or feel overwhelmed by stress? You are not alone.

Here’s a shocking fact. In a 2024 survey conducted with 31,000 people in 31 countries, almost half the respondents – 46 per cent – said they felt burned out by their work.

And, in 2023, stress, depression or anxiety accounted for 55 per cent of all working days lost to illness in the UK.

So what can we do to make things better? Well, the first thing to know might sound disappointing, even defeatist: there is no way to completely banish feelings of stress.

Things will sometimes go wrong, bad luck will befall you, relationships will fail, dreams will be dashed, family members and friends will become ill or die, the world will treat you unfairly. And that’s without mentioning all the little things, and the good things, which can also pile on pressure.

Whatever strategies you use to manage these intense situations, however good you are at putting things into perspective, you’ll sometimes find yourself struggling to cope. And that’s when you’ll feel stressed.

It’s an unpleasant feeling – and at its worst and in the long term it’s bad for mental and physical health.

But it has an upside, too. Indeed, stress is both a symptom of overwhelm and, also, in certain circumstances, a remedy for it.

The fact is, we need some stress in our lives – or we do if we are going to have a full life with a range of experiences.

In a 2024 survey conducted with 31,000 people in 31 countries, almost half the respondents – 46 per cent – said they felt burned out by their work. So what can we do to make things better?

Imagine you’re going for a job interview, or sitting an exam, or playing in a concert, or making a speech. We all know it’s normal to have some nerves, but you might feel so stressed that your sympathetic nervous system kicks in. Your heart starts racing. You break out in a sweat. You even feel physically sick – a result of your digestive system shutting down and blood being pumped to your legs ready for fight or flight.

Sometimes it’s said that this stress response – which has its evolutionary roots in our need to be alert to danger, to be primed for action in the event of a threat to our survival – doesn’t serve us well in 21st–century life.

But the best evidence shows that stress does still serve a useful purpose. Not, these days, in helping us avoid being eaten by sabre–toothed tigers, but in many situations when it matters to us that we put in a peak performance, that we rise to the occasion.

Nerves can sharpen our thinking, helping us to focus and to perform at our best. It’s better understood these days that stress can be a performance enhancer.

So the next time you are faced with a daunting task, it’s worth trying to reinterpret the tension you are feeling in your mind and your body as feelings of excitement rather than anxiety.

Which is easier said than done, but one way you might do this is by reminding yourself why you are in this tense situation.

It’s probably because the outcome is something that really matters to you and, if it goes well, you will feel a sense of achievement and purpose.

Instead of viewing a racing heart as a sign of panic, try viewing it as evidence that you are feeling energised. That this is your body rising to the challenge you’re facing. That your heart is working hard to get you through. That your brain and the rest of your body are fuelling your performance.

Let me tell you about a stressful experience I once had.

It took place in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral in London.

I had been invited to the opening of an exhibition of paintings by people with brain injuries.

BBC psychology expert Claudia Hammond

I didn’t know anyone there, so I looked around the exhibition and said hello to the organiser, and was on the verge of leaving when there was the dinging of a pen on a glass.

The organiser then talked briefly about the origins of the exhibition, before saying she’d spoken enough, now it was time for the main speech by the special guest…Claudia Hammond!

This was, to say the least, a surprise. I couldn’t recall being asked to make a speech, still less saying yes. But there was no time to wonder how the confusion had arisen and whether I had failed to read an email properly.

The small gathering of people had applauded and were waiting expectantly. The only thing I could do was to start speaking.

I’d like to be able to tell you that I immediately viewed the situation as a welcome challenge, and not a horrible ordeal, that I told myself I was excited, not nervous, that I appreciated that my racing heart was my body’s way of telling me that this was important – and then aced the talk. But that’s not quite what happened.

Even so, the stress I was feeling did make me hyper–focused on the task at hand. My brain did sharpen up enough for me to remember some of the paintings I’d just been looking at and to come up with something to say about them.

I’m sure it wasn’t a good speech, but at least I made a stab at it. The audience smiled politely and seemed – or pretended to be – interested. At the end there was a smattering of applause. All in all, I got away with it.

Of course, it generally helps to be prepared when giving a talk or making a speech, just as actors learn their lines or singers rehearse their parts. But, in all cases, you don’t want to be too relaxed, or your performance might come over as lacklustre.

The balancing act is to have done enough preparation to feel reasonably confident, while accepting you’ll also feel nervous and that this nervousness gives you an edge.

The great actor, Dame Judi Dench, put it this way in a magazine interview some years ago: ‘Fright can transform into petrol. I get stage fright all the time; the more I act, the more I feel it. But you just have to use it to your advantage. Fear engenders a huge amount of energy and you have to make it work for the better.’

As Dame Judi Dench says: ‘Fright can transform into petrol. I get stage fright all the time; the more I act, the more I feel it. But you just have to use it to your advantage’

And then there is imposter syndrome. Some years ago, my husband got a new job as the director of communications for a major charity. Having spent more than a decade as a journalist, he understood the media side of the job well, but after many months in the role he still felt out of his depth when it came to another part of his remit: running campaigns.

True, he was picking things up as he went along, and his colleagues didn’t appear to notice that he was busking it, but he was worried that in the end he’d be found out.

So he decided to skill up, to go on a course where he could learn from experienced professionals how to really do campaigning.

He found a day of training sessions which looked ideal, and was just about to book a place when he saw that among the list of speakers was… him (echoes of my unfortunate incident in the crypt at St Paul’s).

I suspect you know how he felt – like an imposter.

Somehow, at a time when his self–confidence was unduly high – perhaps in the first flush of getting the job – he’d been persuaded by the organisers of the course to share his newfound ‘expertise’ with others in the field.

In the meantime, having forgotten that he’d signed up as a speaker, he’d come to a truer realisation of his level of skills and how much he had still to learn.

Fearing you’re an imposter is a feeling that is widespread – research has established that as many as 82 per cent of us experience it at some point in our lives.

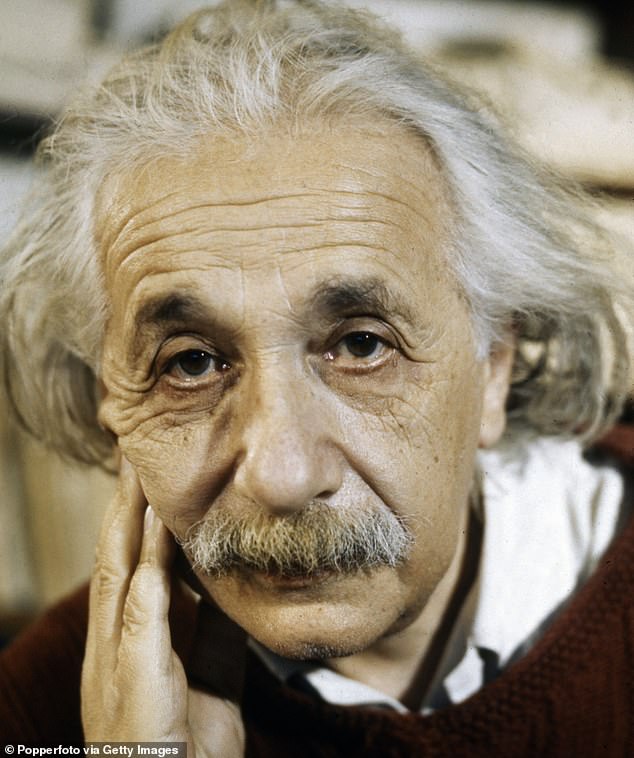

Even the most successful people in the world are not immune. David Bowie, Michelle Obama, Emma Watson, Maya Angelou and Albert Einstein have all talked about feeling like an imposter – talk which can have the effect of making us lesser mortals feel even more inadequate.

Even the most successful people in the world are not immune. David Bowie, Michelle Obama, Maya Angelou, Emma Watson and Albert Einstein have all talked about feeling like an imposter

Imposterism can have true emotional consequences, not least when it comes to feeling overwhelmed, stripping some people of their confidence to deal with situations they could otherwise cope with.

It causes others to put artificial limits on their lives – not applying for a deserved promotion, for example, for fear of exacerbating their feelings of inadequacy.

Persistent and extreme self–doubt can also lead people to feel so anxious and stressed that normal situations come to feel like emergencies or crises.

If this happens repeatedly there’s evidence it can put people at higher risk of burnout. Others push themselves harder and harder to make up for the deficiencies they perceive in themselves.

While this might help with the immediate challenge, it doesn’t help with imposterism because it only reinforces the idea you’ve succeeded not through your own ability, but through graft and luck, something others don’t need because they appear to survive on brilliance alone.

The fact that people who feel like imposters often work extra hard means they can achieve a lot. But this doesn’t break the cycle, because the more they achieve, and the more opportunities they are offered, and the higher they get in their field, the more out of their depth they feel and the greater the fear that they’ll be found out.

Again, there’s a risk of feeling overwhelmed and experiencing burnout. That’s another thing about imposter syndrome: sufferers tend to suffer alone. We think we’re the only true imposter; everyone else is just a fake imposter.

I’ve met people who’ve worked at the heart of government, for prime ministers, and they’ll admit the atmosphere inside Whitehall or No 10 is much closer to the chaos and panic of the TV comedy series The Thick Of It than it is to the well–oiled machine portrayed in the drama The West Wing.

Likewise, the eminent neurosurgeon, Henry Marsh, has admitted that doctors, particularly when starting out, ‘must pretend to their patients that they are more experienced and competent than they really are… you have to inflate your self–confidence, to deceive yourself, to enable you to cut into a fellow human being’s body’.

To come back to my husband, perhaps surprisingly, he didn’t pull out of his speaking engagement. He went ahead and gave a presentation, making the point that his ‘insights’ in this field came from the perspective of an outsider, a newcomer.

He also attended the rest of the course, listening and learning intently from the other speakers.

It would doubtless have been wiser and less stressful for him to have attended this event as a delegate instead, but as it turned out he showed just about the right combination of self–confidence and humility, boosting his sense that he belonged in the charity world without pretending that he knew it all.

This, I believe, is the balance we are all seeking in our lives, and is a crucial factor in managing feelings of overwhelm.

There will always be an element of muddling through in much of what we do, but if we remember that most other people are feeling the same way, we can learn to cope with feelings of inadequacy.

©Claudia Hammond, 2026

Adapted from Overwhelmed: Ways To Take The Pressure Off, by Claudia Hammond (Canongate £20), to be published on January 1. To order a copy for £18 (offer valid to 11/01/26; UK p&p free on orders over £25) go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.

Tips to keep the stress at bay

If you worry a lot, you are not alone. Some even worry about what might happen if they stopped worrying.

The psychotherapist Owen O’Kane found that some of his patients were fearful that if they didn’t worry enough, bad things would happen to them.

Here are scientifically based techniques that can help you reduce your worry levels.

Spot your worry patterns

Keep a diary and note down the times you feel worried and what specific things worry you most.

If you are a worrier, keeping a diary and writing your anxieties down on a page can lower stress

Set aside time to worry

The Dutch clinical psychologist Ad Kerkhof recommends setting aside 15 minutes a day, twice a day, for this exercise. Sit at a table and make a list of all your worries. Then think about them without distraction. You should try only to worry during this time. You are now worrying on your own terms.

Tick worries off your list

Look through your list of worries and decide whether you can let go of any of them. O’Kane suggests writing them in pencil and rubbing them out. Or shredding or burning them. You are symbolically wiping them from your life.

Turn ‘what–ifs’ into ‘so–whats’

Things can go wrong, and they do. But even then, a situation can have unforeseen compensations. There’s the best–case scenario and the worst–case scenario. And what happens in reality generally falls somewhere in between. This is worth remembering when you feel beset with worries.

Try square breathing

Look for a square or a rectangle. A window frame would do. Starting in the top left corner, trace a line with your eye along the top of the square to the corner on the right, all the while taking in a deep breath. Then hold that breath as you trace down the right–hand side, before letting the air out as you mentally trace along the bottom of the square. Pause as you trace back to the top, and then start the tracing exercise again, taking a breath in across the top of the square. You can do this as many times as you want to until you feel calmer. It can be very effective.

Breathing techniques such as square breathing can help relax your body and mind

Why writing a to–do list is a good idea…

A study by Martin Scullin, director of the Sleep Neuroscience and Cognition Laboratory at Baylor University in the US, showed that busy people who create longer lists – with ten tasks or more – fell asleep an average 15 minutes faster than people who didn’t write out to–do lists at all, and six minutes faster than those who only compiled short lists. So it pays to be comprehensive.

It’s important to remember that physically writing down the list is important. Always one for a shortcut, I wondered whether to save time I could just go through the to–do list in my mind. Talking to me on an episode of the BBC’s All In The Mind, Prof Scullin was firm: ‘Writing it down is the way to go. If you are just going through the list in your head, what your brain is going to want to do is to recycle that list.

‘You’re telling your brain this is important information and you don’t want to lose it. And when your brain thinks it’s important information, it’s going to keep on trying to refresh it in your head. If you write it down, there’s less of a chance that your brain is going to do that.’

… and so is a gratitude list

There is another kind of list that’s also a good idea – one that should bring a smile to your face. You may have heard of it, as it’s one of the most popular interventions in psychology.

It goes by various names – a gratitude list, three blessings or three good things.

As you look back on your day, write down three things that went well or that you enjoyed, and then reflect on why these things felt positive to you.

You can choose things big or small. So, as an example, here’s what I might put down today:

I got my favourite seat on the train. There was an amazing sunset as I walked across the park. Netflix has bought my film script for a million dollars. The last item might be a bit of a stretch, but you get the idea.

In research which was conducted in the early 2000s by Martin Seligman and Chris Peterson, two major figures in the field of positive psychology, 411 people were randomly assigned to different groups.

Each group tried out a different psychological intervention, which for one group was to spend a few moments every evening listing three things that had gone well that day and to think about what had caused them to go well.

A control group was asked instead to write about their early memories from childhood.

Within a month, the people who were assigned the three good things task began to show striking improvements in their happiness levels, as well as a decrease in depressive symptoms – with the positive effects lasting for the six months of the study.

Meanwhile, those in the control group saw a brief spike in happiness in the first week, but their mood soon returned to baseline level, and there was no change at the six–month follow–up.

So why does such a simple task have such a big impact on people’s mood?

One reason is that it begins to counter the hard–wired tendency we have as humans to register and remember the negative rather than the positive.

Since 2005, this technique has been shown to work in all sorts of different people, from older women living in Switzerland to teenagers in the poorest parts of Nairobi, Kenya. And a 2021 meta–analysis of studies found that it could even be effective when people had depression.