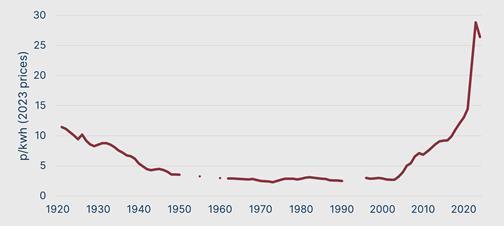

In the second half of the 20th century, the British government maintained a constant flow of cheap, affordable grid electricity. In the year 2000, Britain’s electricity was among the cheapest in the world.

But then things began to go badly wrong. Within a generation, something unthinkable happened: between 2004 and 2024, Britain’s industrial electricity prices rose by over 260 per cent in real terms, from 7.3p/kWh to 26.4p/kWh.

These post-2004 energy price hikes can only be viewed as an energy crisis. It’s a crisis because such a radical rise in energy prices doesn’t just end up costing us more in our bills: it destroys our economy.

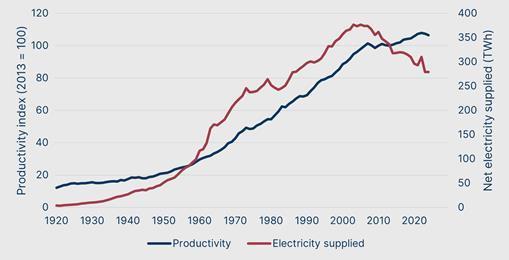

Grid electricity is a key input for most economic activity, so a prolonged and significant increase in its price inevitably suppresses growth. This manifests most obviously by strangling manufacturing and energy intensive industries, but it also can be seen by reducing the general uptake of labour-saving technology. And, perhaps most importantly for our own time, it strangles new industries like data centres in Britain by making them uncompetitive.

Since the late 2000s, politicians and commentators have tried to understand why the output per hour of British workers have stagnated. But they’ve largely failed to make the obvious connection: Britain’s productivity began its long stagnation immediately after total electricity supplied from our grid peaked.

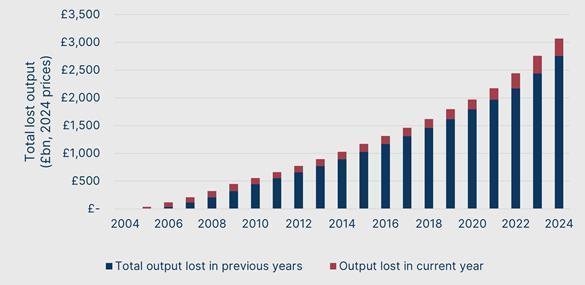

Until now, most commentators have focused on our energy crisis by looking at the direct costs of higher bills. This week, the Social Democratic Party (SDP) has broken ground by being the first British political party to calculate how much our economy has lost because of post-2004 energy price hikes.

We’ve found that, as of 2025, Britain’s productivity is 10.8 per cent lower than what it would have been had real energy prices remained constant since 2004. The output lost to this post-2004 productivity drag from energy price growth is an astonishing £3,060bn pounds. That’s roughly the size of a full year of GDP, or our total national debt.

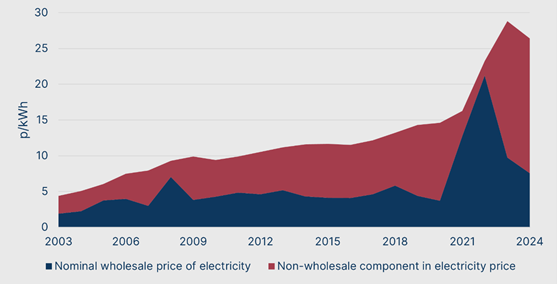

We’ve also shown that most of the post-2004 hikes in energy prices aren’t due to rising wholesale costs. The myth of “expensive gas” is just that — it’s played virtually no role in general energy price growth, aside from a few years of global supply shocks. Instead, 77.6 per cent of the growth in net energy prices since 2004 has been due to non-wholesale costs: mainly policy and network costs.

What caused this? To understand this, we must go way back to the 1989 Electricity Act. Along with privatising the energy system, it removed any centralised planning and forecasting body. It was this abandonment of planning that doomed us.

Politicians allowed themselves to become indifferent to the realities of supplying reliable power, believing the market would sort it out. One consequence of this can be seen in our growing dependence on energy imports — a strategically catastrophic move.

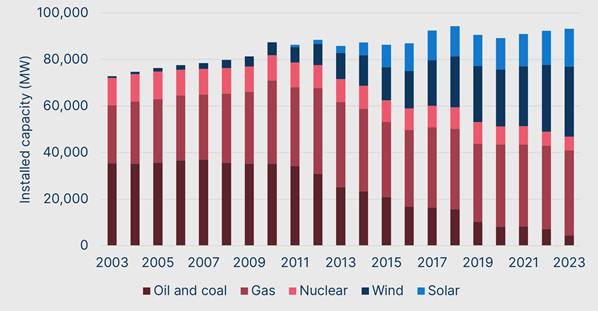

But an even worse consequence of this indifference can be seen through a distortion our political leaders created in the early 2000s: a drive to introduce renewable energy sources like wind and solar into our grid.

Politicians showered the industry with a series of carrots and sticks to introduce intermittent renewables at scale. At the same time, they refused to answer the most basic question — what happens when the sun isn’t shining, or the wind isn’t blowing? They consistently handwaved this fundamental problem away. They deluded themselves into thinking the market could solve this conundrum.

The market did eventually find a solution, with a lot of help from Ofgem, Whitehall, and the global green lobby. Unfortunately for all of us, the market’s solution was to cook the books.

Wind and solar are nominally cheap wholesale sources today, but to account for their intermittent nature the government and energy industry have had to create elaborate mechanisms to suppress energy demand. The post-2004 hikes in non-wholesale energy prices are a perverse, barely planned system of energy rationing that exists almost exclusively to reduce energy consumption and prevent grid failure.

The government is doubling down on this approach. Set up under Miliband, the National Energy System Operator (NESO) is looking to reduce our energy demand by another 54 per cent between now and 2050. This means further price increases to stop people consuming energy when they need it — ensuring further economic ruin in the process.

What can we do about this? In our new Green Paper, Energy Abundance, the SDP has set out an ambitious ten-year plan to fix the energy crisis.

First, we need to stabilise the grid and correct the post-2004 strangling of electricity supply. We’ll fix this by building 20GW of new coal generation and 40GW of natural gas generation, all owned by the state. There’s precedent for projects of this scale being completed at rapid pace: a good example is Egypt, who worked with Siemens to build nearly 15GW of new natural gas power stations within 28 months.

Costing around £60bn, we’ll fund this 60GW of new capacity by abolishing the 2008 Climate Change Act and redirecting the £10bn per year it mandates to be spent on “net zero infrastructure”. We’ll also liberalise oil and gas extraction and nurture a new generation of high-productivity coal mines to ensure these will eventually be fuelled by cheap British energy sources rather than imports.

Second, we’ll build 40GW of new nuclear power stations. We’ll reject the terrible course of action taken by the Hinkley Point C and Sizewell C projects, which have ballooned to well over £12mn per MW of capacity. Instead, using a cheaper design from America’s Westinghouse or Korea’s KEPCO, we’ll target £3.5mn per MW of capacity. Key to this is rejecting the beggaring reliance on private finance, which is a prime reason as to why our current nuclear projects are so expensive and slow. Instead of EDF, these plants will be owned and financed by Britain — benefitting from the lower financing costs of government bonds.

Finally, by the end of our ten-year construction programme, we’ll have 100GW of new generation in the grid. We’ll then rationalise the grid — through natural ageing out of private generators with occasional buyouts, compulsory buyouts of predatory transmission and distribution networks, and refusing to sell energy to so-called “suppliers” — and nationalise it under a single, vertically integrated body named Central Energy.

Central Energy will then be tasked with forecasting and capital spending to maintain a new energy pricing system: one where it can reliably maintain a permanent energy price fix of 10p/kWh. Along with being 60 per cent lower than current prices, this “energy credit” system will tie the value of the sterling and government bonds to the government’s provision of affordable energy. This will reinstate the confidence of energy-intensive industries and manufacturers, encouraging investment and productivity growth once again.

The energy crisis is due to our rulers trading our prosperity for their own self-righteousness. Our new Green Paper, Energy Abundance, is the first coherent rejection of these elite fads in a generation. We hope it marks a turning point in how we all think about energy: away from bureaucratic tricks, market mechanisms and a stubborn refusal to plan towards a state capable of actually building things.

It’s a challenge that requires brute force. And if brute force isn’t working, then we’re not using enough.

You can read Energy Abundance by the SDP at: sdp.org.uk/energy-abundance