AT noon today I will be honoured to join friends in the War Widows Association’s Annual Service of Remembrance at the Cenotaph in Whitehall.

Astonishingly, when the Association was formed in 1971, the widows were not allowed to take part in the better-known Remembrance Sunday service and march-past at the Cenotaph.

They were not considered a “formal military organisation”.

But they were determined to show their respect to their late husbands, so began to hold a very short service on the Saturday, dodging the busy London traffic to lay their crosses, say a short prayer, then dash back to the safety of the pavement.

Thankfully that has all changed, and led by the Southern Highlanders Pipes and Drums, our small group will pause to honour the ultimate sacrifice their loved ones made in the service of our great nation.

During my mere 16 years in the RAF, I served in the Falklands, Bosnia and the Gulf.

But despite my deeply unpleasant experiences of capture and torture as a prisoner of war after being shot down over Iraq in 1991, I think of myself as one of the lucky ones. I survived and returned home to my family.

Many of my friends did not, and they will be at the front of my mind today. I will particularly remember a former RAF Tornado colleague, John “Stan” Bowles, right, who was killed in a mid-air collision over the North Sea in August 1990.

Stan’s widow Debbie is now the vice-chair of the War Widows Association and we will stand alongside each other at the Cenotaph.

A former RAF officer herself, Debbie vividly remembers the day 35 years ago she was told her husband was missing.

Tragically, as Stan’s body was never recovered, Debbie has no physical grave to visit, so the Cenotaph represents an added poignancy and holds a special place to commemorate his service and death.

She says: “The service is always emotional, but it is never depressing. It is a personal acknowledgement of my own loss, but also a wider act of remembrance for all those who have made the ultimate sacrifice for our country, both before and after Stan. It is vital that we never forget.”

When I return to the Cenotaph again tomorrow for Remembrance Sunday, the War Widows will rightly be there too, but this time I will be marching with The Royal Air Force Ex-Prisoner Of War Association.

When I first attended in the mid-Nineties, there were hundreds of World War Two PoWs in our group.

Sadly, there are only a couple still alive, now over 100 years old, and they are unable to join us. So it will just be a handful of my fellow 1991 Gulf War PoWs who gather on Horse Guards Parade behind Whitehall ready for the event.

After the short service on Whitehall, around 10,000 of us will march proudly past the Cenotaph, unveiled by King George V in the aftermath of the First World War, or Great War.

I was staggered to discover the stark reality of that conflict’s casualty figures.

More than one million British Empire soldiers died and more than half a million were either never identified, or never found — lost to the cloying mud of the battlefields, or blasted to pieces by shellfire.

So when the Great War ended in 1918, the nation had been consumed by loss and grief, especially the hundreds of thousands of families who knew nothing of the fate or location of their loved ones.

In an effort to heal the wounds, a grand victory parade was held in July 1919.

A temporary monument was built in the middle of Whitehall which would give the soldiers a focal point to salute as they marched past.

But it was to be only temporary — a plaster and wood structure designed to be demolished after the parade.

It was eventually decided a finer, permanent memorial would be built and unveiled by the King on November 11, 1920 — the second anniversary of the Armistice.

It is also the day that the body of the Unknown Warrior — brought back from the battlefields to commemorate the war’s half a million missing men — was to be interred in Westminster Abbey.

Initially, the King had been less than enthusiastic about the concept of the burial of an unknown man, with concerns that it might “reopen the war wound” after two years of peace.

But eventually, after some political and royal toing and froing, it was decided that both ceremonies would be carried out on the same day.

So on November 8, 1920, four bodies which had initially been buried in graves marked “unknown” near the battlefields of the Somme, Arras, Aisne and Ypres were disinterred and taken to a chapel in northern France.

There they were laid out in front of the altar on stretchers covered by Union Jacks.

I was just staggered by the reality of the Great War’s casualty figures. Over one million British Empire soldiers died and more than half a million were either

never identified or never found

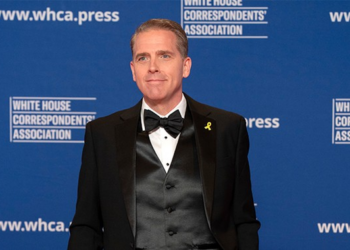

John Nichol

Brigadier General Louis Wyatt, the officer in charge of troops in France and Flanders, then selected one of the bodies, later writing: “I have no idea even of the area from which the body I selected had come, no one else can know it.”

The Unknown Warrior, the one man to represent all the missing, had been selected and was ready to start his journey home.

The body was later placed in a grand oak coffin and amid huge crowds and with great ceremony, taken to London, where it remained overnight on November 10, guarded by troops.

At 10.50am on November 11, 1920 the Unknown Warrior’s gun carriage arrived in front of the flag-shrouded stone Cenotaph, waiting to be unveiled to a huge crowd.

The King stepped forward and laid a wreath of bay leaves and blood-red roses on the coffin.

His handwritten note, tucked into the foliage, read: “In proud memory of those who died unknown in the Great War.

“As unknown and yet well-known; as dying, and behold they live.”

A few years ago at one Remembrance parade I was pushing a fellow serviceman, a prisoner of war from World War Two, in his wheelchair past the Cenotaph.

A girl in the crowd, aged about six, smiled at us and waved a placard. On it, she had painted the words “Thank You”.

I am not ashamed to say her words moved me to tears.

I was fortunate to have survived my wars and be healthy enough to march on the parade and see her message.

Many millions of others are not.

Even though time marches on and our World War Two veterans pass away, the numbers wanting to join the parade increase each year, as does the size of the crowds who line the streets to cheer us on.

It is an acknowledgement that in an uncertain world, our Armed Forces still hold a very special place in the nation’s heart and the notion of service and sacrifice is ever-present.

That’s why today at noon, as I stand in silence at the Cenotaph with widows who have lost so much, not only will I honour the dead, I will be remembering the living they have left behind.

- John Nichol is a former RAF Tornado navigator whose new book, The Unknown Warrior – The Extraordinary Story Of The Nation’s Hero Buried In Westminster Abbey (Simon & Schuster, £10.99) is out now.