Lumber and the American economy.

The lumber market in recent years has been a rollercoaster. For those operating logging businesses, or lumber yards and mills, or contractors and homeowners looking to replace a few planks on the deck, not knowing which way the market will shift has been stressful.

According to a report in the Wall Street Journal:

Wood markets have been whipsawed of late by trade uncertainty and a deteriorating housing market. Futures have dropped roughly 25% since hitting a three-year high at the beginning of August and are trading Monday at about $522 per thousand board feet.

The price drop might have been greater—but two of North America’s biggest sawyers said last week that they would curtail output, slowing the decline.

Crashing wood prices are troubling because they have been a reliable leading indicator on the direction of the housing market as well as broader economic activity.

Quite why they are such an indicator is a reflection of the US construction industry.

Historically, in most of the US, wood has been a local and affordable material for building houses. From the first European settlers, the hardwood forests that covered much of the continent were a bounty of material for houses, ships, furniture, and anything else—as well as a key export commodity.

But its continuing ubiquity as a building material makes lumber prices a good bellwether for the construction economy. Housing in America is overwhelmingly wood-framed. An estimated 90%+ of new residential construction in the US is wood-framed, compared to Europe where houses tend to be brick-built, but with many regional variations (Norway, with ample trees, favors wood for housing).

In other parts of Europe, prefabricated homes are also a much larger share of the market, from an estimated 25% in Germany to a whopping 80% in Sweden (although it is perhaps not surprising in the home of IKEA).

Yet according to the National Association of Homebuilders, factory-built homes were just 3% of the US market in 2023. This is a tiny base, but it is growing. The fad for “tiny houses” and alternative and sustainable options have led more would-be homeowners to consider modular options.

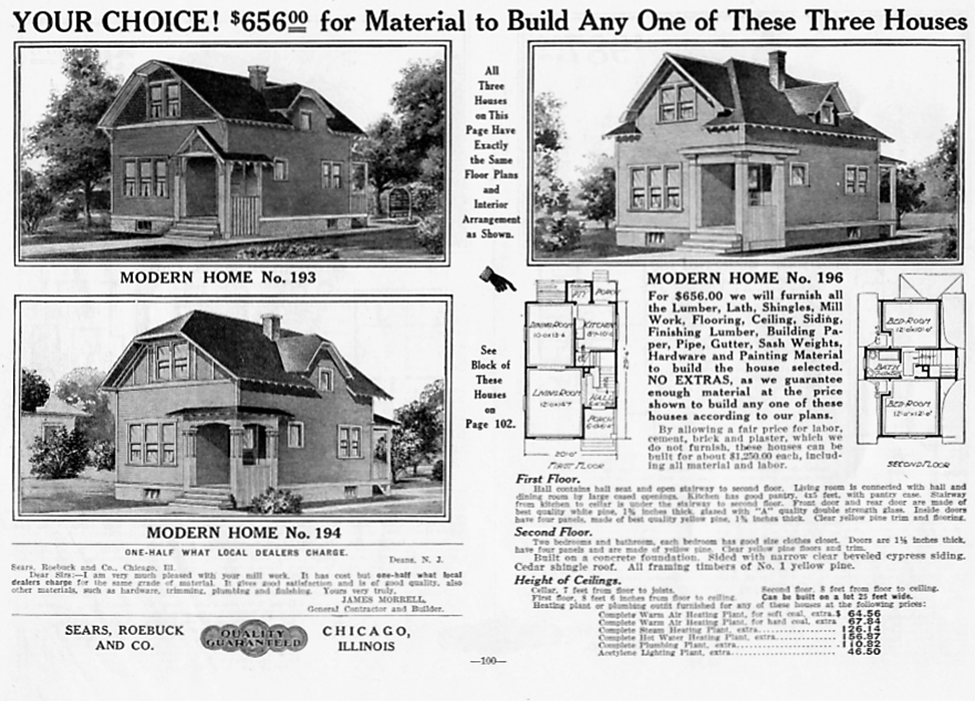

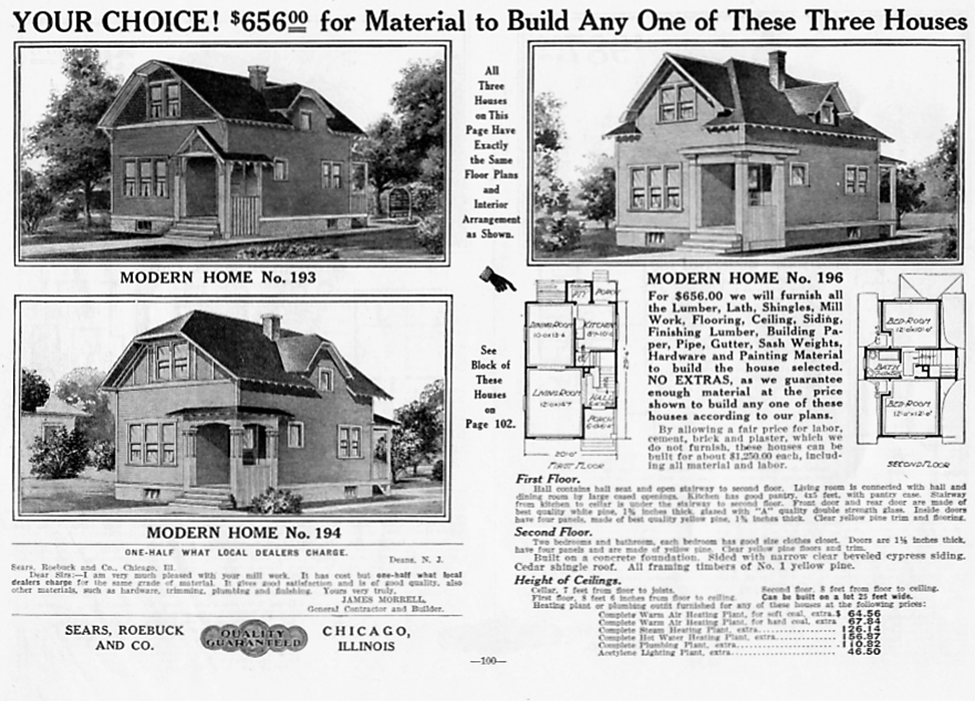

A hundred years ago, kit homes were more common in the US. Sold by Sears, Montgomery Ward, and other local firms, buyers received the plans and the pieces for a house and put it together themselves. Economies of scale made these a viable option for someone looking to build a house in the expanding suburbs.

The 1914 Sears Modern Homes catalog shows three homes that could each be bought for $656 (in the small print, they admit your outlay would be more like $1,250 all-in, including brick, cement, plaster—which they don’t supply—and labor). Your kit house would be delivered by rail; it was generally assumed householders would be handy enough (or know whom to hire) to put it all together from the supplied plans.

According to a 1930 report by the National Bureau of Economic Research, National Income and Its Purchasing Power, in 1914, the average clerk could be making $1,000, and a factory manager earning $2,300. That means these houses were within reach of lots of people—especially bearing in mind that land costs in many cities were also relatively low. In Chicago, lots within 5 miles of downtown were available for less than 50¢/square foot in 1914.

Those kit homes included wood, metal, and glass, and reflected both the tastes of consumers and the economies of bulk production. The various styles in the catalog over the years included craftsman, Dutch colonial, Federal, and cottage—styles that have continued to be popular in residential architecture of the US.

The Sears catalog of 1936 states: “This is the age of modern efficiency. No longer can human hands compete with machine precision and production. ‘Speed with accuracy’ is the watchword in any department of our great factories.”

(For those curious about such houses, fans of Sears kit homes put together lists of examples still standing.)

Today’s prefab homes include different products—in European kit homes around half the materials used being concrete, glass, metal and synthetics—with the same economies of mass production. But wood-and-stick-framed homes continue to dominate the US market.

If the housing market softens, which it looks to be doing, demand for wood will slow and prices drop. Per the WSJ, “Residential building permits dropped in July to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of about 1.4 million units, the fewest since June 2020.”

That doesn’t bode well for timber sellers, but prospective builders could be looking at alternative materials, too.