More than two years after the world was blighted by the outbreak of Covid-19, North Korea finally declared it had recorded its very first case of the virus.

In reality, North Koreans had been suffering the effects of Covid since 2020 like everyone else, often without access to basic medicine and food, according to a new report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

They were also reportedly punished for reporting Covid symptoms, sent to labour camps for not wearing masks or breaking quarantine and in some cases sentenced to years in prison for violating lockdown rules.

The announcement of the first Covid case on May 12, 2022, followed by the acknowledgement of the Hermit Kingdom’s first coronavirus-related death a day later, saw Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un declare a national emergency.

North Korea had already spent some 25 months in lockdown, having sealed its borders in January 2020 – cutting all humanitarian aid – amid concerning reports of the virus from China.

The ‘maximum emergency epidemic prevention system’ plunged Kim’s people into an even stricter lockdown regime and was not lifted until the following summer.

As the restrictions were relaxed, CSIS, a Washington-based think tank, collected testimonies of 100 North Koreans reached via discreet micro surveys conducted by covert interviewers on the ground.

Its report, conducted in partnership with the George W. Bush Institute, found Kim’s regime effectively left the population to fend for themselves in the face of mass infection and rising death tolls and brutally cracked down on cries for help.

In this image made from video broadcasted by North Korea’s KRT, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un wears a face mask on state television during a meeting acknowledging the country’s first case of COVID-19 Thursday, May 12, 2022, in Pyongyang

Pictured: North Korean health workers in hazmat suits disinfect inside the Pyongyang Department Store No. 1 in December 2020. After claiming to have kept the virus at bay, state media said that more than 350,000 people have now shown fever symptoms since late April

Kim Jong Un, center, attends a meeting of the Central Committee of the ruling Workers’ Party in Pyongyang, North Korea Thursday, May 12, 2022

Despite Pyongyang’s official claim of ‘zero cases’ until May 2022, 92 out of the 100 North Koreans surveyed said they or someone they knew had been infected before that date – many as early as 2020.

Entire military battalions, civilian factories and schools were reportedly overwhelmed with sick people.

A woman working in the student/education sector highlighted that conditions were particularly bad in winter 2020 ‘with a lot of cases across the country’.

Within nursing homes, she said, ‘there were so many deaths that there weren’t enough coffins, so I thought it was serious’.

One respondent recounted how half the soldiers in a military communications battalion fell ill during a November 2021 outbreak. Another said students were collapsing in classrooms. ‘Fevers were happening everywhere and many people were dying within a few days,’ they said.

In the absence of any testing regime, diagnosis came down to guesswork.

‘They said it was Covid if you have a fever and cough,’ one person told survey collectors. At the hospital, if a person had a fever and cold symptoms, it was suspected to be coronavirus,’ said another.

One soldier described how doctors were instructed not to prescribe medicine even when symptoms were obvious.

And 20 of the 100 respondents said they were aware of damage, and even death, caused by medicines that were either folk remedies, fake, or not taken properly.

One respondent noted: ‘There were a lot of fake medicines, and people died because they couldn’t use real medicine.’ Another said, ‘There are a few people who died because they should have taken medicine that suits their illness, but if they hear a medicine is good, they start taking it without looking into what it really is.’

With most of the weakened population struggling to access enough food, let alone adequate medicine or vaccines, honesty became just as dangerous as the virus itself.

Official government policy before May 2022 stated that the country had ‘zero’ cases. Respondents indicated that local reports of outbreaks were therefore met with censure and punishments.

‘The clinic doctor told me I have Covid,’ one respondent said, ‘but said if I admit it, I’ll be taken away.’

Just three weeks before acknowledging the outbreak of Covid, Kim held a massive military parade in Pyongyang

Footage of the event on state television showed thousands of people – unmasked and not socially distanced – packed into Pyongyang’s Kim Il Sung square to watch ranks of soldiers goose-step

An official of the Hygienic and Anti-epidemic Center in Phyongchon District disinfect the corridor of a building in Pyongyang, North Korea, on Feb. 5, 2021

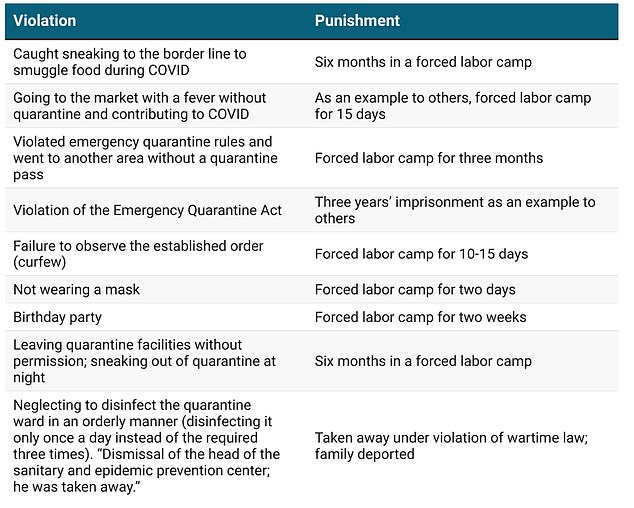

The report also laid out in chilling detail the array of punishments meted out for even the most minor breaches of lockdown rules, based on the interviews with respondents.

Citizens caught breaking curfew were sentenced to 10–15 days in forced labour camps, while holding a gathering, like a birthday party, could earn two weeks behind barbed wire.

The smallest breaches, such as failing to wear a mask would result in two days of hard labour – even as respondents said most people simply couldn’t lay their hands on a mask.

Others fared far worse. Attempting to smuggle food across the border during lockdown was punishable by six months in a forced labour camp.

A harsher penalty was handed to those charged under the regime’s sweeping Emergency Quarantine Act – a deliberately vague and catch-all statute. The punishment was reportedly three years’ imprisonment ‘as an example to others’.

One of the most disturbing entries in the report details the case of a quarantine official who failed to properly disinfect the isolation ward under their supervision.

They were immediately dismissed under wartime law and had their family detained.

However, the largest category of frustrations expressed by the respondents focused on the general ineffectiveness of Pyongyang’s refusal to accept vaccines or other forms of aid from other countries, the report found.

One respondent said: ‘Only my country has closed borders and doesn’t allow travel between regions, and I heard that other countries offered vaccines, but we refused. They don’t care whether the people live or die because they have good quality medicine and got jabs.’

Another noted: ‘The UN said they were going to give our country medicine and rice, but the Supreme Leader stopped them.’

The CSIS report laid out in chilling detail the array of punishments meted out for even the most minor breaches of lockdown rules, based on the interviews with respondents

North Korea was one of only two countries that had not started a vaccination campaign against COVID-19 by May 2022

When vaccines finally did arrive, respondents to the survey claimed that only a select few were able to access them.

‘In my country, only the central party cadres are considered people, and the real people are treated worse than pigs,’ one person said.

‘It was rumoured that everyone would be jabbed when the vaccine came in from China, but only the top officials got it,’ another said, while a third respondent added: ‘Central Committee cadres were jabbed with (vaccines) made in the US. The people are treated like animals.’

The CSIS report did not hold back in its assessment of Pyongyang’s approach to the pandemic.

‘We believe that if the government had spoken truthfully about the pandemic and accepted outside help from 2020, many deaths could have been avoided. Survey respondents all noted increased access to COVID-19 testing and vaccines after May 2022 when Pyongyang admitted to cases of COVID-19 and reportedly accepted some assistance from China.

‘Prior to the regime’s long-delayed announcement of an outbreak in May 2022, citizens reported having virtually no access to vaccines, no antiviral medications, and minimal supply of personal protective equipment.

Moreover, lockdowns of markets and restrictions on internal movements exacerbated food and medicine shortages. It’s likely the national government dealt with the pandemic crisis by shirking responsibility and compelling the populace to fend for themselves.

‘The government’s negligence was nothing short of abominable,’ it concluded.