Air raid alerts are poor substitutes for alarm clocks, but in Ukraine they often perform the same function.

After being woken twice in one night by warnings of incoming Russian drones and quickly rushing to an improvised shelter in the basement of my hotel, I am bleary-eyed the next morning.

However, I discover that many locals consider my reaction a little over the top, with many worn down by a war that looks set to enter its fourth year.

‘I barely listen to the air raid alert app on my phone any more,’ says one resident of Horishni Plavni, halfway between Kyiv and the frontline.

The town is notable for being the site of the Poltava mine, a sprawling iron-ore pit owned by London-listed group Ferrexpo.

Poltava, which was started in 1960 under the Soviet government led by Nikita Khrushchev, is one of the largest open-pit mines in Europe.

Under fire: The Poltava mine visited by the Mail on Sunday

Every year it churns out millions of tons of iron ore pellets, small balls of concentrated metal used to make steel in blast and electric arc furnaces around the world. This is then used for car parts as well as in buildings.

But when we arrive at the pit on a chilly December morning, rather than being greeted by a cacophony of digging machines and enormous dump trucks hauling tons of ore, it is strangely quiet.

I am told production at the mine has been drastically scaled back because of the invasion, which has resulted in manpower, equipment and energy shortages.

Company staff say the only reason the mine is still operating is because it is considered vital to the Ukrainian war economy, and thus certain staff are spared military service – at least for now.

Despite this, the toll of the conflict has escaped no one here. More than 50 Ferrexpo staff have died fighting since 2022, while another 764 are currently serving in the Ukrainian armed forces, nearly 10 per cent of its workforce of 8,000, most of them men.

As in previous wars, women have picked up the slack at the mine. They represent nearly a third of employees at the end of last year compared to 29 per cent in 2021 before the war began.

The number of women in management has also risen from just over 20 per cent to 22.6 per cent last year and is predicted to have risen even further in 2025.

Alongside staffing shortages, the company’s digging machines, many of which are automated or piloted by remote control, have been turned off because the GPS technology they use is being jammed as drones rely on the same tech to fly to their targets.

While the front line is more than 100 miles away, the threat posed by the war is always present.

Less than a week before my arrival in Horishni Plavni, the industrial city of Kremenchuk, just 10 miles away, was hit with a barrage of Russian missiles and drones targeting its power plants and energy infrastructure.

Taking a closer look: Calum Muirhead inspects the site’s kilns in Ukraine

It followed a similar attack in early December that caused electricity, heating and water outages.

While the mine and Horishni Plavni are not often targeted directly, there is always a risk that drones and missiles that veer off course or break down will drop out of the sky.

Yuriy Khimich, one of Ferrexpo’s directors who lives in the area, tells me that a key area of concern is the mine’s storage of explosives, which are used to blast away rock to access iron ore.

He says: ‘The storage has been targeted by drones twice, but both times it has been empty. We got lucky.’

Damage to the electricity grid also presents problems. During our visit, I’m told that parts of the mine and processing plant have been shut off due to a lack of power, hitting production.

The war is also holding up repairs of vehicles and vital mining equipment.

Before Russia’s invasion in 2022, an engine for one of the firm’s massive Caterpillar dump trucks could be replaced within seven days. It now takes up to 25.

A senior technician points to one of the trucks in the repair bay, saying it has been sitting there for 12 months awaiting spare parts.

As we make our way to the parts of the mine still in operation, we are greeted by several hulking examples of post-Soviet heavy industry.

Inside multi-storey warehouses, huge spinning magnets separate the iron from impurities contained in a slurry made from water and crushed rock.

‘If you have a pacemaker, don’t get too close,’ warns one of the production bosses.

This purified iron is then rolled into pellets before being dried and hardened inside a gigantic rotating kiln that heats them to 1,300 degrees Celsius.

‘Stay close,’ my photographer Maksym tells me as we traverse the narrow walkway under the kiln.

‘Sometimes red-hot pellets drop out and fall down the back of your jacket!’ he says, smiling. I cannot tell if he is joking or not.

But while the mine continues to churn out its valuable pellets, it is no secret that the war has placed immense strain on the company’s operations and finances.

Aside from the Poltava mine, Ferrexpo owns two other mines in Ukraine – Yeristovo and Belanovo – which are its newest projects, having been opened in 2011 and 2018 respectively.

In 2021, the year before Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Ferrexpo produced 11million tons of pellets, raking in $2.5billion (£1.9billion) in sales.

Last year, this had fallen to 6million tons while sales were at $933million, less than half their pre-war level, although this was a recovery from 2023 when the company made just $652million.

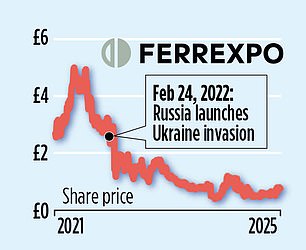

The war has also weighed heavily on Ferrexpo’s share price, which is 70 per cent lower than it was just before Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine in February 2022.

‘It’s been extremely stressful and difficult. I have a very dedicated team who have helped alleviate the challenges. But I would not want to wish this on anyone,’ Ferrexpo’s current boss Lucio Genovese told The Mail on Sunday.

Some analysts say the company’s share price has effectively become a proxy for predictions of when the war will end.

‘Any sign of a return to anything akin to normality could be a boost for sentiment towards the shares,’ said Russ Mould, investment director at stockbroker AJ Bell.

He added that while the company had proven ‘very resilient’ during the war, pressure would ratchet up as more local infrastructure is damaged and more staff are called up to fight.

‘Mining stocks can be volatile at the best of times, given how demand is often linked to the vagaries of the global economic cycle, and pricing is often set by the producer with the lowest cost of incremental production,’ he said.

‘Ferrexpo comes with added, direct geopolitical challenges.’

Aside from suffering the effects of the Russian invasion on its operations, the company is fighting battles on the home front with the Ukrainian authorities.

In March, the government decided it would suspend refunds of VAT to the company’s two main subsidiaries in Ukraine.

So far, the freeze has cost the firm $47million, according to an update in October, when it announced 20 per cent of its workforce had been placed on furlough or reduced hours to save on costs.

Ferrexpo has also found itself in the crossfire in a row between the Ukrainian government and its largest shareholder, billionaire Kostyantyn Zhevago, who controls 49.3 per cent of the business.

Ukraine’s anti-corruption authorities have charged Zhevago, who was previously the group’s chief executive, with embezzlement and bribery, allegations that he denies.

The authorities have tried to have the tycoon, who has been sanctioned in Ukraine, extradited from France. But in October a French court rejected the request citing the risk of an unfair trial.

And earlier this year, the Ukrainian government launched a bid to partially nationalise the Poltava mine by seizing Zhevago’s stake in the company.

Genovese told The Mail on Sunday that the company has become a ‘victim’ in the legal battles between Zhevago and the Ukrainian government.

‘All these litigations relate to Zhevago and his previous dealings with other businesses…We’ve asked the authorities many times for them to deal with Mr Zhevago on these matters and keep Ferrexpo away from these issues. But unfortunately we’ve been used as a tool to put him under pressure.’

He added that the firm supported efforts to root out corruption that has blighted Ukrainian politics and business dealings in the post-Soviet era.

‘We try to run our business as best we can and stay out of trouble…To us it’s always a good thing that corruption is exposed and dealt with in the proper way.’

His comments come after Volodymyr Zelensky’s government was rocked in November when his top adviser Andriy Yermak, a key interlocutor with Ukraine’s allies, resigned after his home was raided by anti-corruption authorities in a growing probe into graft in the energy sector.

His departure followed the sackings of energy minister Svitlana Grynchuk and justice minister Herman Halushchenko.

Several suspects have been detained or fled the country.

The mounting pressure on the company comes as it also tries to reintegrate a steady stream of employees who have returned from the front lines, many of them suffering from injuries and mental conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder.

Some 204 veterans have been discharged from service, but only half have since returned to work.

Some of the mine’s managers tell me that while demobilised staff are guaranteed a job upon their return, some are kept away from ground operations as the noise of mining equipment and explosive blasts can cause distress.

We meet a group of these demobilised staff at a newly-constructed war museum in Horishni Plavni funded by company money.

One wall is covered with the faces of Ferrexpo staff and other townspeople who did not return from the front.

The firm has funded equipment such as first aid kits, body armour and supply backpacks for those serving, but due to the financial pressures after years of war this is becoming increasingly difficult.

Serhiy Valkoviy, a veteran who organises the group of demobilised employees, says the current pile of equipment the company can provide is now at ‘a critically low level’ but attempts would still be made to supply soldiers.

‘We will try to the best of our ability,’ he says.

Attempts to get veterans to open up about their experiences are also being promoted, although the process is slow and difficult, with many unwilling to speak.

It is at this point, shortly before power shortages force the museum to shut off its lights for another blackout, that the future of the mine and the people who live on its doorstep seemed inexorably intertwined by the chaos of a conflict that has rumbled on for nearly four years.

Valkoviy tells me that the company, like the people of Horishni Plavni, understands that the sacrifice of the servicemen is worth more than the cash needed to support them.

His voice wavers with emotion: ‘It is because of them that we can continue to exist. They are our heroes.’

DIY INVESTING PLATFORMS

AJ Bell

AJ Bell

Easy investing and ready-made portfolios

Hargreaves Lansdown

Hargreaves Lansdown

Free fund dealing and investment ideas

interactive investor

interactive investor

Flat-fee investing from £4.99 per month

Freetrade

Freetrade

Investing Isa now free on basic plan

Trading 212

Trading 212

Free share dealing and no account fee

Affiliate links: If you take out a product This is Money may earn a commission. These deals are chosen by our editorial team, as we think they are worth highlighting. This does not affect our editorial independence.