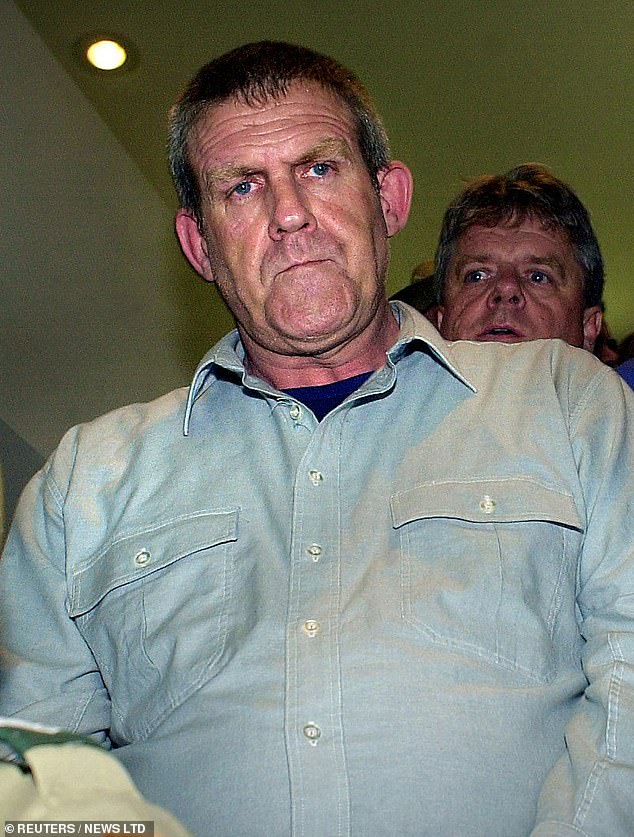

For a time, the face in that photograph was one of the most famous in the world.

Instantly recognisable: the craggy, weather-worn skin, the belligerent, challenging stare, Bradley John Murdoch was a man not to be messed with. The sort of rough, bush-dwelling, hard-living, authority-defying Aussie you wouldn’t want to lock eyes with across a bar.

How many times had I looked at that face… and wondered.

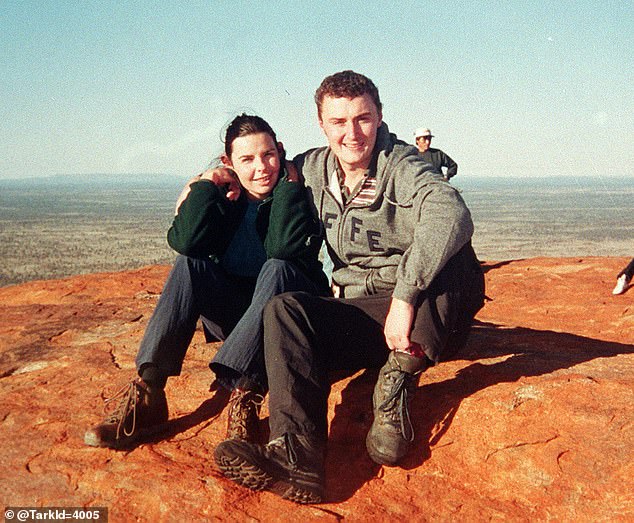

After his arrest in August 2002, nearly a quarter of a century ago, Murdoch’s face was all I saw, in newspapers or flashed up on TV, where it was usually accompanied by another set of pictures, of a smiling young couple: a woman with shiny, bobbed black hair and toothy grin sitting alongside a young man with a wide, friendly face.

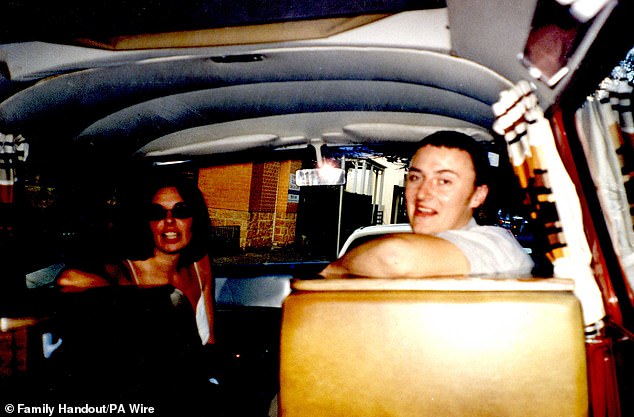

They were Joanne Lees and Peter Falconio, a pair of British backpackers who were ambushed as they drove their VW camper van along a remote highway, north of Alice Springs, Australia, one bitterly cold night in July 2001.

Peter, 28, was murdered – probably shot in the head at close range – and his girlfriend, Joanne, 27, trussed up and bundled into the assailant’s truck, before she staged a dramatic escape, hiding in bushland for five hours as the killer stalked her.

At the time, I was working as the Mail’s Australia correspondent, covering this case that had gripped the world. And it was not long after his arrest that I found myself face to face with the man the police were convinced did it.

In a stroke of blind luck, Murdoch, a 47-year-old drifter, mechanic and drug-runner, with a string of convictions, had been picked up by police on an unrelated case and a DNA match had placed him at the scene of the Falconio murder.

Peter Falconio, 28, and his girlfriend Joanne Lees, 27, pictured together in Australia

Bradley John Murdoch was a man not to be messed with. The sort of rough, bush-dwelling, hard-living, authority-defying Aussie you wouldn’t want to lock eyes with across a bar, writes Richard Shears

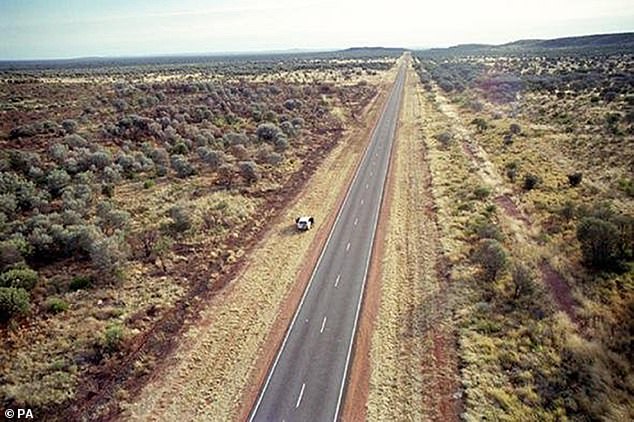

The Stuart Highway in the remote bush of the Northern Territory, where Peter was murdered by Murdoch on July 14, 2001

What’s more, he wanted to talk, and the prison authorities gave permission for me to visit him at the Berrimah jail, in Darwin. He was awaiting trial for the alleged rape of a 12-year-old girl and her mother – charges he denied and for which he was subsequently cleared. But of course, all everyone wanted to talk to him about was the Falconio case.

A burly figure, towering over my own 6ft 2in frame, there was no hesitation as he walked towards me across the prison yard in his blue and yellow prison uniform.

He wasted no time in getting to the point: ‘You’re going to ask me, did I do it?’ he said with a smirk. ‘Even from inside here, if I could get a few bucks for answering that question I’d be a rich man,’ he said.

‘But did you do it?’ I asked.

‘Joanne has her story and I have mine,’ he said. We went back and forth with this frustrating exchange for 15 minutes with no definitive response. His attitude was almost playful. ghoulishly mischievous.

Murdoch, who travelled extensively through the Outback in his white four-wheel-drive vehicle delivering cannabis, was no stranger to the law, and how to play it, and here he was playing me. I came away from that interview feeling no closer to the truth.

Along with the rest of the world, I caught my breath when that same face appeared on TV again this week, after the news that Murdoch, serving life for Peter’s murder and Joanne’s attempted kidnap, had died of throat cancer at the age of 67.

He died still protesting his innocence and, most cruelly for Peter’s family, refusing to reveal where he had buried his body.

Murdoch being arrested by South Australian police in Adelaide in November 2003, more than two years after he murdered Peter

Peter and Joanne pictured together. Joanne escaped from Murdoch by hiding in remote bushland for more than five hours after he held her at gunpoint

I spent around five years immersed in this deeply disturbing story, travelling through some of the world’s most remote and hostile terrains, to speak to those who knew Murdoch. I was granted exclusive access to his parents, former workmates, girlfriend and ultimately the prisoner himself. They were encounters I will never forget.

Of all the crime cases I have covered in more than 50 years as a journalist this is the one that has troubled me above all others.

Murdoch had been arrested in a supermarket in South Australia on August 28, 2002. Like everyone closely following this story, I rejoiced at the news as the manhunt over the previous year had been intense.

After his arrest, he was found to be carrying a gun, and his white Toyota truck fitted the description Joanne had given. A DNA sample was taken and forensic scientists compared it with a tiny smear of blood on the T-shirt Joanne had been wearing. It was a definite match – 150 quadrillion (150 million billion) times more likely to have come from Murdoch than from anyone else – prosecutors were told.

Although he was cleared of the rapes, as far as the Falconio case was concerned, the police had their man.

Yet as I investigated further, troubling questions emerged in the prosecution’s case, which weren’t helped by Joanne’s sometimes confused and inconsistent testimony about what happened to her that night.

So let us remind ourselves of the events of July 14, 2001, when Joanne Lees and Peter Falconio set off on their ill-fated trip. She was a travel agent from Hove, he was a building contractor from Huddersfield, and they were driving along a highway, about 200 miles from Alice Springs.

At around 8pm, a white truck caught up with them, and the driver indicated there was something wrong with their van’s exhaust. They pulled over, and Peter got out and joined the other driver at the back of the vehicle while Joanne moved over to the driver’s seat.

Joanne said she then heard a bang – like a gunshot or the exhaust backfiring as she revved the engine. Then a stranger appeared at the driver’s door, a man of average height, with a moustache and long, straggly hair, who pointed a gun in her face.

He managed to restrain her with a pair of homemade cuffs and partially bound her ankles. He then threw a sack over her head and forced her into his vehicle. But she escaped and, still shackled, crawled into the wilderness, before being picked up by a passing driver five hours later.

Peter’s death was confirmed by a pool of his blood found on the highway, but soon questions started being asked about Joanne’s version of events.

Murdoch, his family and friends emphasised time and again, was a giant of a man, 6ft 4in tall, and had always worn his hair short, nothing like the description of the long-haired attacker provided by Joanne. And why did this big, heavy man leave no footprints in sandy bushland as he, and his dog, walked around looking for Joanne? I’d spoken to Aborigine trackers, brought in to hunt for clues, and they’d found only Joanne’s sandal marks in the sand – not Murdoch’s prints or those of his dog.

Also, Murdoch had no teeth – a fact I could vouch for, having stared into that grotesque grin in the prison room – yet Joanne never mentioned it, despite being face to face with him.

Then there was his truck: Joanne claimed she’d escaped by climbing from the front through to the rear, yet the cab was sealed. Also, his trusty hound Jack was a Dalmatian, but Joanne recalled seeing an animal with a reddish-brown coat.

But superseding everything was that irrefutable DNA sample: DNA doesn’t lie. Yet even that wasn’t as clear-cut as everyone hoped. Forensic experts who picked up the tiny speck of blood questioned why there wasn’t more, given how close the two were and how violently she had struggled.

The next time I spoke to Murdoch was in 2005, as he awaited trial for the Falconio case, this time at the Alice Springs Correctional Centre. Again, he was coolly confident, and, for a man with little or no education, had an awful lot to say about DNA. He was being framed, he said, by a police force that was terrified by the world attention and desperate to salvage its reputation.

‘It’s got to be obvious what they are doing,’ he said. ‘They are going to throw a DNA case at me because there’s nothing else.

‘It will be all part of their plan to close me down and lock away the Falconio case,’ he said, before adding, cryptically: ‘I have one particular enemy who’s been collecting my DNA.’

Intertwining his big fingers, he said: ‘Everybody knows that the van Peter and Joanne were driving had all manner of people in it and that’s where the confusion will arise in my case.

‘They’d picked up a couple of German tourists at Kings Canyon and there are people bumping up against one another all the time.’

In a reference to carrying guns – police found a fearful collection of weapons in his truck, including an electric cattle prod, a shotgun, a box of ammunition, two pistols, several knives, a crossbow with 13 bolts and Russian-made military-style night-vision glasses, rolls of tape and ten cable ties – of course he was ‘tooled up’, he said. ‘The business I was in, everybody knows about that, was very dangerous,’ he said. (His drug-running, taking cannabis between South Australia and the north west town of Broome, was well-documented and never denied.)

‘I’m not in the motorcycle gangs any more. I don’t have their protection. It was generally known I was driving through the desert with a big amount of money. I was very careful, there could be no risks of any kind.’ He was convinced he’d be cleared.

Around this time, Murdoch’s parents, Colin and Nance, agreed to meet me at their home in Perth, western Australia. A friendly, working-class couple, then in their 60s, they could have been anyone’s mum and dad. They served me tea and biscuits in their humble bungalow and were keen to talk about their wayward boy.

Yes, he was a tough man, they said, but not the psychopath depicted in the media. ‘Please understand this,’ Colin told me, clutching my arm. ‘My son is not a killer. If I thought he had done this, believe me I would know it.’

‘Big Brad’ as he was known, hadn’t had an easy childhood. Money was tight and they’d led a transient life, travelling around the country, looking for work. There was tragedy, too. The couple’s 23-year-old son, Robert, died of cancer when Bradley was ten, affecting him badly.

‘He would have turned out good, but he got pulled away by the wrong people as he was growing up – those bike types, the gangs, a bad marriage. [Murdoch married a woman called Diane in 1984, and they had a son together before separating two years later.] It all worked on his mind,’ said Colin.

Yes, there were ‘skirmishes’ with Aborigines who lived nearby, and with ‘druggies’, his parents said. Murdoch had served 21 months in jail for shooting at a group of Aborigines he claimed were harassing him. ‘It’s true he got into fights with some local gangs but he ended up on top, except that time he got his leg broken in a fight.’

Colin gazed at family photos on display in a cabinet, pointing out they were from Bradley’s boxing days. ‘He didn’t win everything,’ said Nance, as she showed me one photo of Brad, with his missing front teeth.

‘So he got his teeth knocked out?’ I asked.

‘Oh no,’ she quickly corrected me. ‘He lost them because he was eating too much chocolate.’

I stared into his face for seven long weeks during his trial in Darwin in 2005 and watched him, stony-faced and impassive, as the guilty verdict was read out.

It was the last I saw of him – until this week, when his image dominated headlines again and I was reminded of something he said the last time I interviewed him. ‘Let me tell you this, mate, the truth will come out some day. I just have to be patient.’

Peter Falconio’s family may never have peace, may never be able to bury their boy. And, I fear, we will never know the full story about this case, which continues to haunt me to this day.