Once upon a time, and despite a history of anarchist, Fenian, Nazi and anti-colonial threats, the level of physical security infrastructure in Westminster and Whitehall was puny. Prime Minsters and their ministers walked unaccompanied from government department to Parliament. Downing Street was still a public right of way. I walked down it myself as a child. Bobbies patrolled. Uniformed guardsmen and retired soldiers manned ministerial front doors, but had a concerted mob attempted to rush any door they would doubtless have affected an entrance. Due to the twin threats of Irish and Islamist terrorism all has now changed: gates, fences, bollards and heavy balusters are everywhere to block cars, gunmen, mortars and suicide bombers. Dignified and uniformed concierges have been replaced by contractors in high-viz jackets. Sad but seemingly inescapable.

However, in a happy riposte to the erroneous cliché that “form follows function”, for thirty years enlightened souls ensured that this new generation of antiterrorist infrastructure was aesthetically attractive. Following consultation with English Heritage and the Royal Fine Art Commission, the steel gates outside Downing Street erected in 1989 are actually rather enjoyable. Alternately sized vertical standard bars are topped with spearhead and shell-shaped railing heads. The comely posts have castellated finials. Two lavishly ornamented torchères provide both light and height. Look carefully and you will see acanthus leaves, volutes and palmettes. This is not minimalism. But nor is it insecure. The gates’ twin functions of providing security and seemly elegance are inescapably intertwined. Spearheads are hard to climb over. Posts and torchères are providing extra strength. Even if there were no policemen with submachine guns this gate would be hard to overcome.

The low and thick security walls that now line Whitehall and Parliament Square were added in 2008-9. They are perhaps a little heavy. It’s hard not to be if you are built to withstand a tank. But they somehow achieve elegance: a well-proportioned plinth, portly and creamy Portland stone balusters, beautifully formed lamps as finials. Ultra-secure bi-steel nestles within.

In 2012, new railings were added to Cromwell Green outside the Palace of Westminster after it was invaded by Greenpeace protestors. Downing Street’s design patterns reappear but with more of a Gothic twist, appropriately for Britain’s most famous neo-gothic building. A quatrefoil string course, ribbon-like finials and vertical standard bars with spearhead railing heads keep the public out. But they also let the public see in. Westminster Hall and Hamo Thornycroft’s martial statue of Oliver Cromwell remain supremely visible.

The designers of Downing Street’s gates, Cromwell Green’s fence and Whitehall’s anti-car walls were not just aligning security and elegance. They were also aware of the traditions within which they were operating. Look up at Sir John Soane and Charles Barry’s Cabinet Office, at Sir George Gilbert Scott’s Foreign Office or at John Brydon’s Treasury along Whitehall and you will see along the roof the same pattern of segmented balusters and robust finial decorations that has been echoed below. The anti-tank wall along Whitehall may be new. But it rhymes with roofs which are centuries old.

Similarly, the modern designers of Downing Street’s gates and Cromwell Green’s railings were palpably aware of Westminster’s rich tradition of ornamental iron work, a tradition which had its origins in precisely the same desire to marry status with security. Throughout the eighteenth-century West End, ornamental railings were introduced to secure garden squares, houses and commercial and public buildings from footpads and thieves. Over 200 years a whole language was created of piers and plinths, wall-struts and dog-rails, railing heads and finials, spearheads and urns. These historic railings were also serving the same dual purpose as in Whitehall or Westminster: lending dignity to those within and keeping pickpockets and robbers without. Westminster’s public buildings, such as Buckingham Palace, GE Street’s Royal Courts of Justice or Charles Barry and Augustus Pugin’s Palace of Westminster, played more elaborate variants on the same melody. New Palace Yard’s original Victorian railings, designed by Charles Barry’s son, Edward, are a stunning display of decorative security with iron spikes, crowns, roses and fine twisted balusters.

Many of Westminster historic railings were ripped out performatively and uselessly in World War II to “make tanks” (it was the wrong metal) but in a little noticed heritage success over the last 50 years most have been replaced with historically accurate replicas with the strong and wise support of Westminster City Council.

In replacing their lost ironwork, Westminster City Council has been rightly rediscovering an ancient tradition. The concept of protecting elegantly is noble and well established. Medieval barons enhanced their castles with more arrow slits and crenelations than security required. Michaelangelo sketched fortresses for visual appeal. And George Dance designed Newgate Prison with more external charm than any modernist town hall. The Palace of Westminster itself deploys the protective crowned portcullis as a ubiquitous motif, carved in stone, stamped on leather and cast into metalwork, including the very form of the Great Bell, “Big Ben.”

Their Lordships’ new prison fence totters between the ignorant and the mocking

Which brings us to the recent traducing of this tradition and the melancholy saga of the modern House of Lords. No British building better defines Britain to the world or to itself than the Houses of Parliament. Across the centuries, architects have normally believed that the most precious and the most sacred buildings in our towns and cities should be the biggest, the most set apart and the most beautiful. For generations that was our churches following the advice of the Roman Vitruvius or the fifteenth century Florentine, Alberti, who wrote that a church should be the noblest ornament of a city and that its beauty should pass imagination. As religion declined in Victorian England, the New Palace of Westminster, constructed with breathtaking aplomb after the fiery and catastrophic 1834 destruction of its predecessor, passed on the baton of what was most precious from church to nation and from clergy to public service. Its miraculous creation was nothing less than the sanctification of the unwritten English constitution and of the supreme and shared power of the Crown-in-Parliament. It was and remains the perfect admixture of sensible Whiggery (sanctifying the practice of daily parliamentary debate) and profound Toryism, with its sumptuously ornate celebration of the Monarch’s periodic visits.

However, just as the need for beauty in design has recently been reestablished in English planning, thanks to the work of Fiona Reynolds, the late Roger Scruton, the Building Better Building Beautiful Commission and my own colleagues at Create Streets, the House of Lords seems to be ignoring this fine tradition of comely modern insertions into fine old buildings and to start trashing its own heart, history and heritage.

The House of Lords recently spent just under £10 million (not a typo) ruining the historic Peers’ Entrance and replacing it with a rotating door that is as ugly as sin, does not work, causes queues and requires constant and expensive attendance to be kept partially functioning. It is not just an insult to the management of public funds. Its gratuitous ugliness is an affront to Parliament’s symbolic importance, a glass plated insertion into an old friend, a triple failure of function, cost management and love.

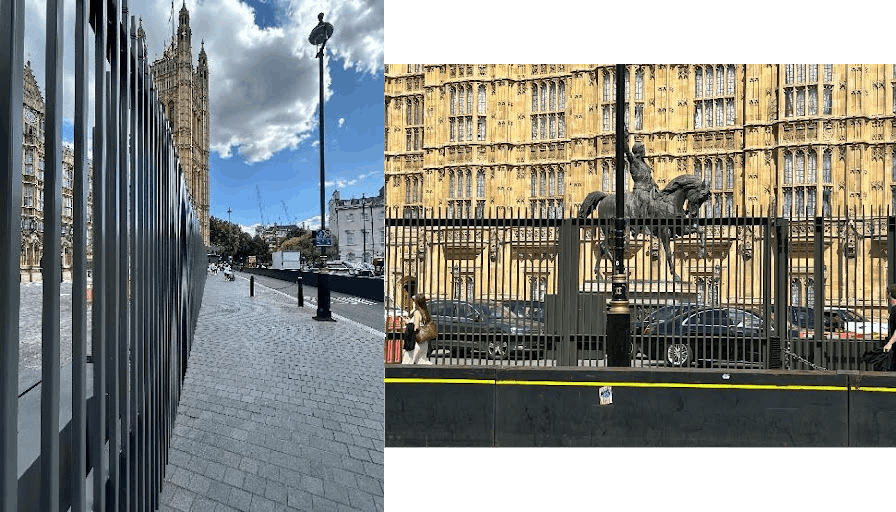

In case anyone should think this was merely bad luck or a “one off”, the powers that be in the House of Lords have decided to leave nothing to chance. They have done it again but this time even more offensively. Peers arriving at work last month were shocked to discover that the ugliest security fence in any modern British city centre had been erected overnight around Old Palace Yard and Peers’ Entrance. The House of Lords authorities decided to plump for what might be termed the USA/Mexico border aesthetic, or, if you prefer, Greek/Turkish frontier chic. Personally, it calls to mind a rather unpleasant border crossing I made between Kyrgyzstan and China about 20 years ago, a memory replete with heavy guard dogs and bribes to small men with large guns. It is not a great look for the mother of parliaments.

Repetitive, featureless, blocking the view in or out through the atonal thud of its undecorated prison-like bars, the new fence is the epitome of design as a tuneless and functionalist response to a narrowly conceived “design problem”. It has no more understanding of the symbolism or sanctity of parliament than does my dog of the far side of the moon. No one involved seems to have asked if hiding a parliamentary behind prison bars was appropriate. No one seems to have been aware of the fine tradition of Westminster’s decorative security ironwork exemplified by every single neighbouring building and by other parts of the House of Lords. In its reckless unconcern for the building it is obscuring, the new House of Lords fence is the equivalent of the stained urinal as an artform or of the moustache graffitied upon the Mona Lisa.

According to one peer, “staff here are now calling the place, HMP Westminster.” But it’s not just depressing to see or walk past. According to Lord Dobbs, one of a growing number of disgruntled peers, the fence is failing as a security barrier as well: “every policeman and custodian that one asks says that the fence which has just been erected is dangerous, as it cuts off sightlines for those who might be wishing harm on this place. How have we spent more on this front door and this fence than on the Grenfell Tower disaster?”

Faced with a growing litany of questions, the House of Lords authorities are refusing to reveal the cost of their lordships’ new prison walls. They have also told peers that the reason they could not follow the wise approach taken 13 years ago at Cromwell Green is that the new fence has to be bolted to three-metre-long steel bottom blast barriers that are portable and can be moved for the State Opening of Parliament. This is nonsense. There is no reason at all why attractive fencing cannot be attached to blast barriers just as it is normally attached to a stone plinth. Nor is there any reason why the steel blast barriers cannot be masked with stone to “look” like normal stone plinths as has been done in Parliament Square or Whitehall.

The new prison fence definitely fails the City of Westminster’s excellent policy on the design of railings for listed buildings. This policy states that “alterations to Listed Buildings should normally be entirely in accordance with the period style and detailing of the original building or with later alterations of architectural interest.” The new fence almost certainly represents “substantial harm” (an important planning concept) to the Palace of Westminster as a Grade I listed “heritage asset”. (The only conceivable reason it might not is the movable nature of the fence). Nevertheless, I am certain that this visual abomination would not in normal circumstances conceivably have received planning or listed building consent. (Technically, the Palace of Westminster which is sovereign does not need planning consent. They voluntarily submit applications to the City of Westminster. Nearly all details have been redacted, however, from the City of Westminster website.)

The Palace of Westminster is also a UNESCO World Heritage site of “universal value” due in part to being “an outstanding, coherent and complete example of neo-Gothic style.” UNESCO particularly worry about the erosion of site lines which this visually impenetrable new prison fence clearly does. According to UNESCO, any major change such as a new fence needs a “heritage impact assessment”. I cannot find any evidence that this has happened.

One peer tells me that “the vast majority of peers are appalled since we knew nothing about it. The small number who were sold this pup on the Commission now say that they did not know that it would be so big or ugly.”

Their lordships are right to be very worried. This is a design catastrophe. It undermines the heritage, aesthetics, symbolism and very function of a transparent modern parliament. It erects a needlessly visually intrusive and ugly barrier between parliament and the people. This is a public building which we have just needlessly made less public.

Their Lordships’ new prison fence totters between the ignorant and the mocking. If those involved in its creation have any understanding of British history then they are satirists. Presumably foreign delegations still come on ambassadorial visits to the Palace of Westminster. If they do, then one lesson they will certainly take from these prison walls is “don’t employ British designers.” What a melancholy message.

There is, however, hope. One rare unredacted detail on the City of Westminster planning portal is that this is a “temporary” planning application for ten years. This was probably the deal to get this monster through planning. Doubtless, the hope, once shock has faded, will be quietly to upgrade the temporary consent to a permanent one without anyone noticing.

So my Lords, there is your opportunity. You can certainly get rid of this horror a decade hence. Can you get rid of it faster? Can you replace it with something elegant and appropriate as has been possible in every other comparable security barrier in Westminster and Whitehall?

To the barricades my Lords, you have nothing to lose but your prison walls. You have built a fence. And trashed a legacy. Pull it down again. And put up something worthy of our past, our present and our future.