For centuries, the Rub’ al-Khali desert near Saudi Arabia and Dubai — known as the Empty Quarter — was dismissed as a lifeless sea of sand.

But now, it’s revealing an astonishing secret.

In 2002, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, ruler of Dubai, spotted unusual dune formations and a large black deposit while flying over the desert.

That led to the discovery of Saruq Al-Hadid, an archaeological site rich in remnants of copper and iron smelting, which is now believed to be part of a 5,000-year-old civilization buried beneath the sands.

Researchers have now found traces of this ancient society approximately 10 feet beneath the desert surface, hidden in plain sight and long overlooked due to the harsh environment and shifting dunes of the Empty Quarter.

The Rub’ al-Khali spans more than 250,000 square miles, making it the world’s largest expanse of continuous sand.

This discovery brings fresh life to the legend of a mythical city, believed to have been swallowed by the desert as punishment from the gods.

Moreover, people believed the Empty Quarter desert hid a lost city called Ubar.

For centuries, the Rub’ al-Khali desert (pictured) in Arabian Peninsula — known as the Empty Quarter — was dismissed as a lifeless sea of sand. But now, it’s revealing an astonishing secret

According to legend, Ubar was buried beneath the sand after being destroyed — either by a natural disaster or, as some stories say, by a god punishing its wicked residents.

T.E. Lawrence, the British officer and writer famous for his role in the Arab Revolt during World War I, called Ubar the ‘Atlantis of the Sands.’ He described it as a city ‘of immeasurable wealth, destroyed by God for arrogance, swallowed forever in the sands of the Rub’ al-Khali desert.’

Now, cutting-edge science may be catching up to ancient myth.

Researchers from Khalifa University in Abu Dhabi employed Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) technology to penetrate the desert’s surface, a tool that allows scientists to peer beneath the dunes without disturbing them.

SAR works by sending out pulses of energy and measuring how much bounces back.

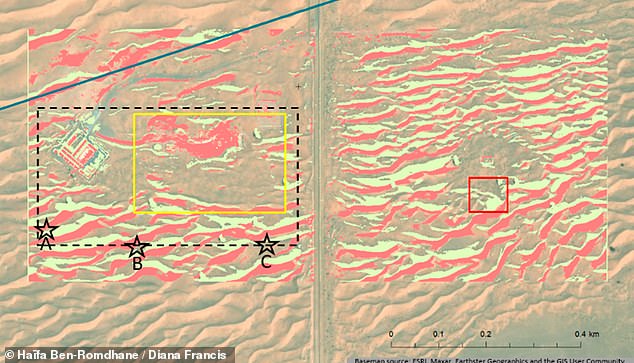

In this case, archaeologists combined SAR data with high-resolution satellite images from WorldView-3 to scan beneath the desert sands at Saruq Al-Hadid.

The radar detected buried structures and revealed clear signs of metal production, artifacts, and layers of animal bones in what archaeologists call midden deposits.

By analyzing the radar data with advanced machine learning algorithms, researchers could identify patterns and shapes that pointed to ancient human activity. This method allowed them to uncover parts of the lost city.

Traces of a 5,000-year-old civilization have been found buried approximately 10 feet beneath the Arabian desert, hidden in plain sight of ‘Saruq Al-Hadid’, an archaeological site

The findings suggest a complex, interconnected society that thrived in the region thousands of years ago.

Researchers identified previously unknown settlements and roadways, which are strong indicators of long-term habitation and organized civilization.

Layers at the site show bedrock, sand dunes, and patches of gypsum, with plenty of artifacts, ancient metal waste, and animal bones found throughout.

SAR technology — when combined with AI — is increasingly becoming a game-changer for archaeological surveys, especially in environments where traditional excavation is nearly impossible.

‘The case study of the Saruq Al-Hadid site illustrates the potential of these technologies to enhance archaeological surveys and contribute to heritage conservation efforts,’ according to the research published in the journal.

Layers at the site show bedrock, sand dunes, and patches of gypsum, with plenty of artifacts, ancient metal waste, and animal bones found throughout

To validate the remote sensing data, researchers compared it with existing archaeological records and conducted field checks.

The findings were accurate enough to prompt action from Dubai Culture, the government body overseeing the site. Excavations have now been approved in the newly identified areas.

‘These regions remain largely unexplored, yet we know they hold cultural history,’ Francis said.

While little is currently known about the people who lived there 5,000 years ago, the discovery is already transforming our understanding of early civilizations in the Arabian Peninsula.

The Arabian Desert has been inhabited since the early Pleistocene, with Neolithic and Paleolithic tools found in the southwest Rub’ al-Khali. Bedouin nomads adapted to desert life, focusing on camel herding, date farming, and oral storytelling — cultural practices that echo the resilience of ancient desert societies.

Despite its current hyper-arid conditions, the region experienced periods of increased humidity between 6,000 and 5,000 years ago, forming shallow lakes due to significant rainfall events. These lakes supported diverse ecosystems, including flora, fauna, plants and algae — all crucial clues in painting a fuller picture of life in what was once thought uninhabitable.

With each pass of the radar and layer of sand peeled back by science, the Empty Quarter is proving it was never truly empty.