This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

This has been a year of Thatcher anniversaries. We marked the centenary of her birth in October, whilst February marked 50 years since she became Leader of the Opposition after the Tories had lost two elections in quick succession. Anyone who hasn’t read Charles Moore’s monumental three volumes can now enjoy his pellucid prose in more compact form.

Margaret Thatcher: the Authorised Biography (Allen Lane, £40) has been edited by Daniel Collings into a single chunky volume, but he has omitted little of substance apart from the scholarly apparatus. Strongly recommended for millennials and anyone tempted to confuse showmanship with statesmanship.

Anyone looking for a life of Thatcher shorter than the 1,104 pages of Moore’s abridged tome, would be well advised to avoid Tina Gaudoin’s The Incidental Feminist (Swift, £22). Her thesis, that her subject is owed an apology by feminists, is reasonable enough. But Gaudoin offers no evidence, just hearsay, for her sensational claim that the Iron Lady conducted at least one affair whilst in office. Iain Dale’s Margaret Thatcher (Swift, £16.99), by an author who knew her well, is shorter, sharper and better written.

From the dame de fer to a femme fatale — but fatal only for the enemies of Western civilisation. Melanie Phillips has been fighting a one-woman culture war for decades, and The Builder’s Stone (Wicked Son, £17.99) is her summa. The subtitle reads: How Jews and Christians Built the West — and Why Only They Can Save It. The book does what it says on the tin, and Phillips’ argument, made with her usual pungency, is unanswerable.

Jung Chang, another formidable and inimitable female voice, has been a thorn in the side of the Chinese Communist Party ever since her Wild Swans took flight in 1991. 34 years later she has written the sequel: Fly, Wild Swans: My Mother, Myself and China (HarperCollins, £25). This tells the story of her life since she left the People’s Republic in 1978, leaving behind her mother who, together with her grandmother, played a central role in Wild Swans.

This is a story of success beyond her wildest dreams, but it is bittersweet: even today, as her mother fades away, aged 94, Jung Chang cannot go back to the nursing home in Chengdu to be at her bedside. Her memoir is a reminder that Xi Jinping’s regime is as pitiless as Mao Zedong’s but far more of a threat to the West.

What, though, do we mean by “the West”? Where does the idea come from and is it really in decline, as cultural pessimists since at least Oswald Spengler have been asserting for more than a century? In The West: The History of an Idea (Princeton, £35), Georgios Varouxakis illuminates such questions in a deeply erudite yet highly readable work that lays many myths to rest.

Varouxakis may have written the most original history book of the year, but there are other serious contenders. Roger Chickering’s The German Empire, 1871 — 1918 (Cambridge University Press, £40) shows how it was Bismarck’s empire, not the Weimar Republic, that set the stage for Hitler’s Third Reich. In the age of Putin and Trump, we must jettison the assumption that Western nation states will necessarily adhere to liberal democracy. From the perspective of 2025, Chickering writes, “the German path of development after 1871 looks less retrograde than precocious”.

No less suggestive about the present day is John Hardman’s The French Revolution: A Political History (Yale University Press, £25). This vivid narrative, at times as evocative as Dickens or Carlyle, sparkles with aperçus: “The tragedy of the French Revolution is that the rule of lawyers failed to bring about the rule of law.” Hailed at the time by Charles James Fox as “the greatest event that has happened in the history of the world and … the best”, the Revolution utterly failed to establish its three principles of liberty, equality and fraternity.

Instead, it installed a new ruling class of “notables” to replace the old nobility. These bastard offspring of the Revolution, who emerged from the grand guignol of the guillotine, are still running France today.

As a case study in restoring a neglected genius to contemporary significance, we are indebted to Matthew Bell for his Goethe: A Life in Ideas (Princeton University Press, £35). An uomo universale who outdid even Leonardo and other Renaissance men in range, Goethe was a one-man civilisation. But Bell doesn’t disguise the flaws of this freethinker with a weakness for autocrats. Napoleon was always his Emperor. How many intellectuals since Goethe have fallen under the spell of world-historical monsters?

A case in point is the Franco-Russian thinker Alexandre Kojève. Chiefly remembered today for his Introduction to the Reading of Hegel, Kojève was the inspiration for Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History. It was he, not Sartre, who first brought existentialism to France. But he was also one of the architects of the European Economic Community and, according to French intelligence, a Soviet spy.

A new biography of this Mephistophelian master of disguise by the Italian Marco Filo has now been translated by David Broder as The Life and Thought of Alexandre Kojève (Northwestern University Press, $38).

Nobody could accuse Seamus Heaney of capitulating to totalitarian temptations. Always a man of the left, he nevertheless avoided the ideological pitfalls of a Catholic Northern Irishman of his generation. The Poems of Seamus Heaney (Faber, £40) has now been edited and annotated by Rosie Lavan, Bernard O’Donoghue and Matthew Hollis. It clocks in at over 1,200 pages and includes assorted hitherto unpublished verse.

Together with the poet’s Letters (edited by Christopher Reid) and Translations (edited by Marco Sonzogni), this handsome volume completes the Heaney corpus, apart from his occasional prose pieces.

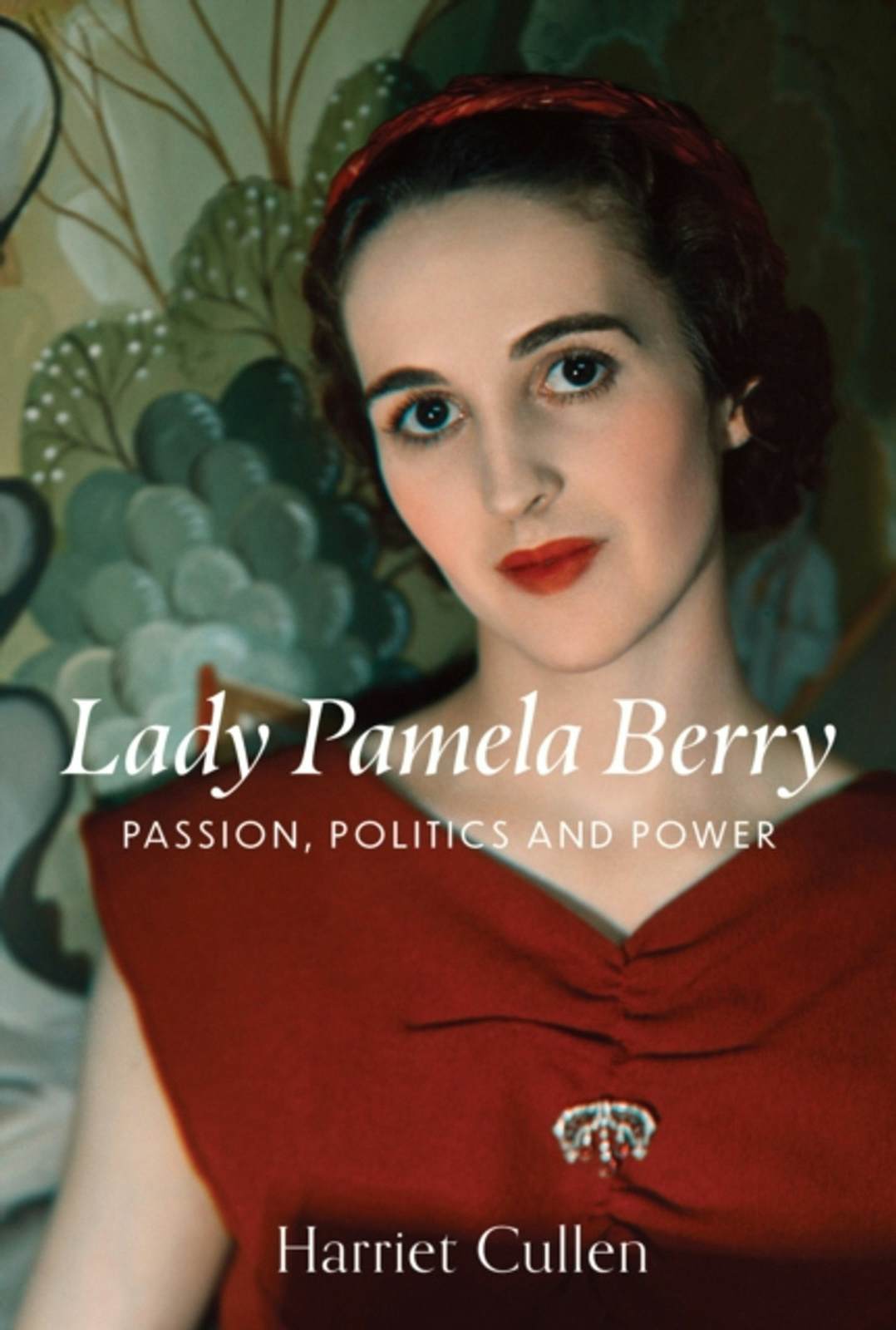

Readers in search of lighter fare might enjoy Lady Pamela Berry: Passion, Politics and Power (Unicorn, £25) by Harriet Cullen. The author is the daughter of Pam, as she was known to her vast social network — which encompassed the political, journalistic and intellectual elites of the mid-twentieth century. Hers was a life spent exercising influence behind the scenes — a life that no woman would or perhaps could live now.

Though she was denied the “glittering prizes” of which her father F.E. Smith had spoken, Pam was far more than a lady who gave glittering lunches. She helped to bring down a prime minister by persuading her husband, Lord Hartwell, to let the Daily Telegraph criticise Sir Anthony Eden for lacking “the smack of firm government”.

Pam certainly did not lack political passions, but as my father — a devoted but (unlike Malcolm Muggeridge) platonic friend — said, “she felt debarred by her sex”. She lived just long enough to see that barrier fall. Labour have had no female leaders, the Tories four. The latest could, if she gets the chance, prove to be this century’s best PM so far.