‘Mummy, I love you very much’.

These were the devastating last words of 13-year-old Omayra Sanchez, who died a slow and agonising death while the world watched from their television screens.

For nearly three days, the school girl remained trapped in the wreckage of her family home after Colombia’s Nevado del Ruiz volcano erupted on November 13, 1985 – unleashing a wall of mud that wiped the entire town of Armero off the map.

The teen spent 60 hours trapped from the waist down under the cement-like lahar, while emergency services worked tirelessly to free her.

But her tragic plight quickly captivated the world, after Red Cross rescue workers were forced to give up their efforts to help her when it became apparent that they would not be able to give her life saving care.

Rescuers, photographers and journalists spent Omayra’s final moments with her, taking it in turns to comfort her and keep her company, bringing her fizzy drinks and sweets.

The tragedy was heavily documented, with harrowing videos and images of Omayra reaching households across the world.

This photograph taken by Frank Fournier of Omayra Sanchez was taken shortly before she died after becoming trapped in lahar following a volcanic eruption in Armero, Colombia in 1985. The image later became the World Press Photo of the Year on 1986

Omayra Sanchez died on November 16, 1985 after being trapped in volcanic mud for over 60 hours after a volcanic eruption struck the Colombian town of Armero. Omayra is pictured in this image on the day she died

Omayra Sanchez floats in muddy water after being caught in a lahar as it flowed from the erupting Nevado del Ruiz volcano in Colombia. The 1985 eruption completely destroyed the town of Armero, killing 23,000 of its inhabitants

Omayra appeared on Colombian television addressing her mother just hours before her death

Her last words are believed to have been caught on camera, after Colombian broadcaster RCN aired a video of Omayra showing her with bloodshot eyes as she remained submerged in the muddy water.

Addressing her mother, a nurse who had travelled to the capital Bogota for work before the disaster unfolded, Omayra said: ‘Pray so that I can walk, and for these people to help me.

‘Mummy, I love you very much, daddy I love you, my brother, I love you’.

After 60 hours, Omayra’s hands went white and her eyes turned black, and not long after, she died.

On her third and final day, rescue workers say Omayra began to hallucinate, telling bystanders she was worried about being being late for her maths exam.

She also told those keeping her company to go home so that they could rest.

After her death, it was found that her aunt’s arms were tangled around Omayra’s legs.

But it was one particular image of Omayra, holding onto life as rescuers tried to free her body from the mud, that became emblematic of the tragedy and continued to capture the world’s attention in the days after the disaster.

The Nevado del Ruiz volcano in eastern Colombia had been dormant for several years, meaning that authorities did not take the prospect of an eruption seriously, despite warnings from experts

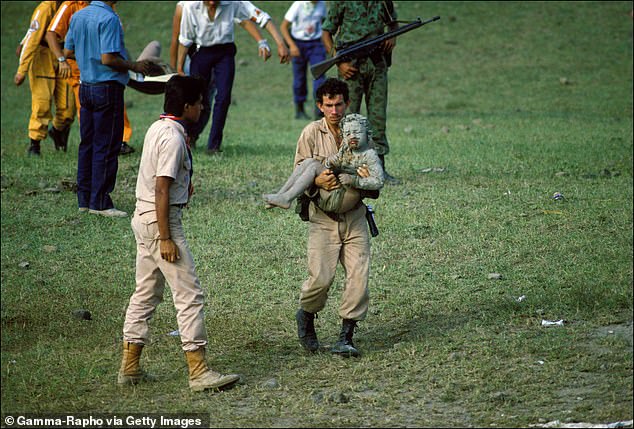

Pictured: Emergency workers attempt to rescue Omayra after she was trapped in debris and lahar from the eruption

Omayra’s last words are believed to have been caught on camera, after Colombian broadcaster RCN aired a video of her addressing her mother

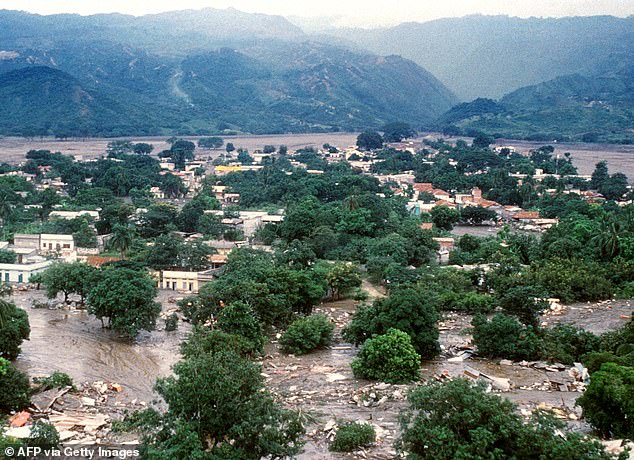

The town of Armero was completely wiped off the map after it was destroyed by mudflow

A volunteer carries a child covered in mud after the eruption of Nevado del Ruiz in 1985

French photo-journalist Frank Fournier captured her final moments in a heartbreaking photograph, which went on to win the World Press Photo of the year in 1986.

Fournier received backlash from public, with several questioning why he didn’t help Omayra as she took her last breaths.

But in an interview with the BBC, the French photographer spoke about how it was impossible to save her and defended his decision to take pictures of her before her death.

‘There was an outcry – debates on television on the nature of the photojournalist, how much he or she is a vulture. But I felt the story was important for me to report and I was happier that there was some reaction; it would have been worse if people had not cared about it.

‘I am very clear about what I do and how I do it, and I try to do my job with as much honesty and integrity as possible. I believe the photo helped raise money from around the world in aid and helped highlight the irresponsibility and lack of courage of the country’s leaders.’

‘There was an obvious lack of leadership. There were no evacuation plans, yet scientists had foreseen the catastrophic extent of the volcano’s eruption.

He also recalled her final moments, explaining how ‘dawn was breaking and the poor girl was in pain and very confused.

‘When I took the pictures I felt totally powerless in front of this little girl, who was facing death with courage and dignity. She could sense that her life was going.’

Rescue workers carry an injured person, caught in a lahar flowing from the erupting Nevado del Ruiz volcano in Colombia, on a stretcher

When the Nevado del Ruiz erupted, it melted part of its snowcap, creating a 150-ft-high wall of mud that swept down the Lagunilla River

Another 2,000 people were killed or disappeared on the opposite side of the volcano

Red Cross rescue workers were forced to give up their efforts to save Omayra when it became apparent that they would not be able to give her life saving care. Picture shows destroyed homes in the town of Armero following the devastating Nevado del Ruiz eruption

Fournier added: ‘People still find the picture disturbing. This highlights the lasting power of this little girl. I was lucky that I could act as a bridge to link people with her. It’s the magic of the thing,’

Speaking about Omayra, Fournier recalled that the girl was ‘an incredible personality’.

‘She spoke to the people trying to save her with utmost respect, telling them to go home and rest and then come back’.

Omayra lived with her father, younger brother and aunt at the time of the tragedy, all of whom died instantly after being swallowed up by the deadly lahar.

Her mother Maria Aleida Sanchez had travelled to Bogota to work as a nurse, who helplessly watched on from the capital as her daughter’s state declined.

Thirty years after her daughter’s death, Maria spoke fondly of her daughter in a 2015 interview.

‘Omayra loved studying. She was very special to me, and she adored her brother. She had her dolls, but she hung them on the wall. She didn’t like playing with dolls and was dedicated to her studies’.

The volcano, that overlooks the town of Armero in eastern Colombia, had been dormant for 69 years, and so residents and authorities didn’t fret much about the possibility of an eruption, nicknaming it the ‘sleeping lion’.

The volcano, that overlooks the town of Armero in eastern Colombia, had been dormant for 69 years

Volunteers work to free Primo Gomez who is tapped by debris from the eruption of Nevado del Ruiz Volcano in Armero, Columbia on November 15, 1985

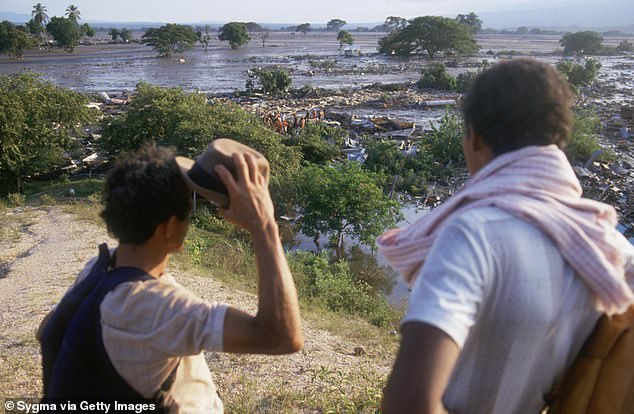

Two men look out over a field of mud, where a lahar from the erupting Nevado del Ruiz volcano flowed into a valley in Colombia

Image shows the Nevado del Ruiz volcano

Scientists had warned of a deadly eruption for months, but no response plan was put in place.

When the Nevado del Ruiz erupted, it melted part of its snowcap, creating a 150-ft-high wall of mud that swept down the Lagunilla River.

About 23,000 of Armero’s estimated 28,000 residents died or went missing as the mudslide pulled trees from their roots and enveloped entire homes.

Another 2,000 people were killed or disappeared on the opposite side of the volcano.

It took relief workers 12 hours to reach Armero after the devastating eruption, which meant victims who had sustained serious injuries were already dead.

The town, once known as ‘the white city’ was littered with fallen trees, human bodies and piles of debris.

Armero has since remained a ghost town after its surviving inhabitants relocated to the nearing towns of Guayabal and Lerida.

What is left of Armero are destroyed buildings, vehicles and cemeteries to commemorate the thousands of lives that were lost.