Escape and evasion is at the heart of what the SAS is all about. The regiment often operates behind enemy lines so its men are much more likely to be separated from comrades or captured, and need to know how to evade a larger enemy force. This was the climax of the gruelling SAS selection course that had seen many ejected already, for which I – a black, working-class kid – was one of the few survivors.

We returned to the freezing Welsh hills where we’d begun the selection process, to be pushed to the edge of our physical and mental capabilities. We were blindfolded and driven to an unknown mountain and moorland spot, handed a sketch map and told to rendezvous with an ‘agent’ at a particular location. When we reached the first checkpoint, we would be given another location, a mouthful of bread and cheese, and sent on our way. This process was then to be repeated over and over.

Each wearing just an old Second World War-style greatcoat and a pair of laceless boots, we were let loose to be hunted by more than 1,000 soldiers who’d been promised a bonus if they captured us. They were accompanied by helicopters and police dog-handlers. The local farmers had been told to inform our hunters if they spotted anyone suspicious on their land.

It was only possible to move at night; if you tried during the day you were guaranteed to get caught. And if you were spotted anywhere near a road or a track, you were instantly off the course. So we had to try to navigate over marshes and hills in the dark. If caught, you’d be beasted for a few hours, then released again.

On the first night I split up with the man I’d been paired with as we sprinted blindly away from hunters whose torches we’d spotted approaching us.

For hours I splashed across streams to throw dogs off my scent. Then I found a ditch, made a tunnel by pulling branches over myself and had lain there through the day lashed by constant rain.

By the evening I was hungry, cold and wet and shivering uncontrollably. My legs and arms had been ripped to shreds by thorns.

The greatcoat wrapped around my shoulders was so sodden that I doubted it offered any warmth at all, but nor could I contemplate abandoning what was my only piece of outerwear.

Melvyn Downes realised that making the cut for Special Forces would be tougher than he ever imagined

Mr Downes served in Iraq before applying to join the SAS – ‘Escape and evasion is at the heart of what the SAS is all about,’ he wrote

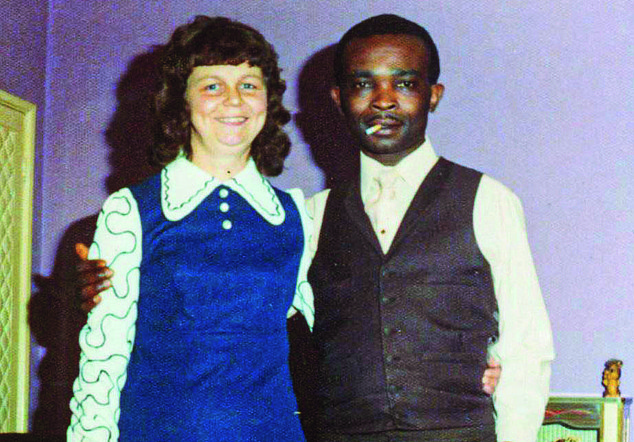

Mr Downes had a tough childhood, sometimes going hungry. (Pictured with his parents aged 16)

Then I heard high shrieking yells. The dogs were near again. The hairs on my arm stood on end, my heart pounded. I knew this wasn’t real, yet I had persuaded myself it was. That I was being chased, that I might be tortured or killed if I was captured.

I’d figured that if I raised the stakes like that, I’d be less likely to throw in the towel when I was tired or hungry or cold or fed up.

The barks grew closer, accompanied by the muffled sounds of men talking as they swarmed through the area, their feet bringing them closer and closer to my hideout.

I needed to control my breathing and rein in my fear. That way I would be less likely to give off the pungent scent we produce when frightened and which the dogs would pick up. The voices were more distinct now, I heard the dogs panting. Damn, was this the end?

I’d chosen a spot so choked with nettles and rotting mulch I was sure nobody would stop to investigate it, but what if I’d made some stupid error that led them to me? My mind cycled through all the possible options.

They were just metres away. Twigs snapped, grass tore. My heart started to thump, so I turned my attention to my breathing again. Please, I thought, don’t let me be captured.

Then the sounds grew more distant, before disappearing. They were somebody else’s problem now. A few minutes passed, I dared a glance through the thatch of plants. Night was falling. It was time to move.

One, then two, then three and four days and nights went by. It was the last day of this stage. The end was in sight, though we knew that in a sense our suffering had just begun. If we made it through, ahead were countless hours ‘in the bag’ – meaning the bags placed over our heads before an interrogation process that would test us to the limit and maybe beyond. I’d never felt so feeble or alone. I wasn’t sure if I was ready for this.

Mr Downes joined up at 16 and instantly loved everything about the army

Pictured: Mr Downes as a young child in the seventies – Mr Downes led operational tours in Iraq and Northern Ireland and served more than two decades in the armed forces

Pictured: Mr Downes With CBS News and the UN in Darfur in 2005 – He said working alongside journalists gave him a totally new perspective on the world

It was a daunting prospect. I knew they’d do everything to break my mind. If they break your body, you can almost always find a way back. If they break your mind you risk being lost for ever.

I was contemplating this as I walked in the dark through ragged woodland. I thought I spotted a face leering at me through foliage. There was someone there, a man with wild eyes and sunken cheeks, his skin almost black with dirt.

The face broke into a crooked smile. It was Sammy, one of the oddballs on the course, a Marine in his mid-30s – towards the upper age limit – trying to get into the SBS, the Special Boat Squadron.

We’d joked that he looked like Krusty the Clown from The Simpsons. He still did, though only if Krusty had spent the best part of a week hiding in a filthy trench while packs of dogs hunted him.

I giggled at the thought, then realised I probably looked just as repellent. He came towards me and asked: ‘Did you see that farm over there?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘What have you had to eat?’

‘Hardly anything, just a few roots.’ Sammy had an idea: ‘Let’s go see what food we can find.’ He had a point. We didn’t know what exactly we were going to face while being interrogated but it stood to reason we’d need as much energy for it as we could muster.

He went off to investigate and rushed back a minute or two later with a triumphant smile.

Mr Downes said as soon as he got his uniform he started to thrive – he was Britain’s first black SAS soldier

At just 20 Mr Downes was in charge of 8 men in their 432 armoured personnel carrier

Good, he’s found some food, I thought. My mind ran away with me; a loaf of bread perhaps, or even brown bananas. I wasn’t picky. ‘Look at this,’ he whispered, brandishing a plastic bottle in my face. Salad cream.

I examined the label. ‘It’s three months out of date. No way am I eating that. I don’t want to get ill.’

‘Come on, have some!’ he insisted. As I shook my head, he picked up a stick and started jabbing it into the bottle, bringing it up coated with thick gobbets of the salad cream. ‘This is lovely.’

Sammy and I stuck together, right up to when we were stopped by masked men who grabbed us, planted bags on our heads and shoved us on to the back of a truck of horse manure.

As more and more candidates were picked up, they were hoisted on to the truck, thrown carelessly so they landed painfully on the blokes below.

The truck rattled, our nostrils filled with the stink of excrement and the bodies of men who’d spent days living in the wild.

I reminded myself of the instructions we’d been given about what we were allowed to reveal. Name, rank, number. Nothing else. And if we signed any piece of paper put in front of us we’d fail the course immediately.

Straightforward enough, you’d think, but when you’re exhausted and disorientated and on the wrong end of the tricks of experienced interrogators, it’s anything but.

Melvyn Downes said selection for the SAS pushed him right to the very edge of my mental and physical capabilities, but he loved the jungle stage

Mr Downes’ parents pictured in the seventies – Mr Downes signed up for the army aged 16

After a while we were bundled off the truck and led to the interrogation centre, where our blindfolds were removed. It was dark and I could see very little. But I could instantly feel a change in the air temperature. For the first time in a week, I was warm.

Instantly I began to feel drowsy, almost swaying on my feet. Perhaps I dozed while standing there, waiting for my turn, perhaps I didn’t; I cannot be sure.

I do remember being led into an even warmer office and the way the interrogator deliberately started talking to me in a soothing Canadian accent.

I tried to focus but everything in my mind seemed fogged. I began to drift off. I was going deeper into sleep. Then his voice broke into my consciousness again. ‘Thank you for telling me about your wife and kid.’

I came to with a start. Had I? No, this is a trick. I turned to the man sitting beside him, trying to work out whether I’d really given this information away. This didn’t help because he appeared to have turned as silent as Mickey Mouse.

The interview ended and I was hauled out, bewildered and not confident I hadn’t betrayed myself. I’d learn later that an officer on the course had been persuaded to put his signature on a document. Once he’d crossed that line, he started cheerfully signing paper after paper. That was the end of him.

When we weren’t being interrogated, we were forced to sit blindfolded in a stress position, cross-legged, back upright, with our hands on our heads. If at any point you slumped, or fell asleep, a guard would be on you in seconds, slapping you to bring you back up.

Before long, every limb was filled with excruciating pain, our discomfort made worse by strobe lights flashing in our eyes and white noise blasting in our ears.

Mr Downes in South Armagh in Northern Ireland known as Bandit Country

Mr Downes in Northern Ireland – he was sent for a second time as a peacemaker

Occasionally a cup of water would be brought to our lips to sip. We had to p*** where we sat. Sometimes they strode over and started beating us. The worst was a guy who seemed to enjoy it.

Finally, I was brought into an interview room, where they told me to strip naked. There was a bloke I’d seen before and a new inquisitor, a good-looking blonde woman. I couldn’t help but notice how tight her black top was. They made me open my legs, touch my toes, pull my butt cheeks apart. It was nasty, humiliating, though nothing I couldn’t cope with.

Then the interrogation began. To begin with it was standard good cop, bad cop, switching between threatening me and offering hot food and a shower if I signed the piece of paper they slid across the table to me.

I imagined standing beneath a cascade of warming water that soothed my aching limbs and washed off the dirt that encrusted every inch of my skin. My hand twitched. My God, it was tempting. It couldn’t hurt, could it? With an effort I dragged my mind back to the room and shook my head. ‘No,’ I said, smiling.

My sense of reality felt frayed. But I had one thing to hold on to. It would soon be over. I knew that in July it got light at about 4am. I also knew the interrogation phase usually finished at around 11am. And that would be it, I’d have done it.

I was sure I’d seen a glow of light through my blindfold and that an entire rotation had passed since then. This was the last block of four hours I needed to survive.

The woman leaned across the table. Something in her face changed, her eyes filled with malice. She pointed to my penis. ‘Pull your foreskin back.’ I did what I was told. ‘Now pull it forward.’ I obeyed. She repeated the instructions. Baffled, I carried on. Then she sneered: ‘Are you w****** over me, you disgusting n*****?’

Right, I thought, this is the game, is it? To be honest there was no word she could say that I hadn’t heard as a black kid growing up on a council estate in Stoke-on-Trent.

Melvyn Downes During the first Gulf War in 1990 where he led his patrol into combat

Her insults took a more demeaning turn. Then, somehow, as she edged that bit closer to me, and I saw her chest in my eyeline and smelled her perfume, I imagined her naked. It was just for a fleeting second, but it was enough. Blood rushed to my penis; it jerked upwards. Oh, God.

She noticed immediately and did her best to control her reaction. A smile flashed across her face, then after a brief struggle, she laughed. And I did too. It was all so ridiculous. And yet it could mean me failing the course, even at this late stage. We’d been told we had to take it all seriously.

The idea that this might be the reason I got chucked off felt cosmically unfair.

And yet, I wondered, maybe it was a weakness in me they’d managed to find. That’s what they were here to do. Panic mounted in me.

As I contemplated this, she managed to master herself. ‘Get that black b****** the f*** out of here!’

I was blindfolded, dragged out and thrown on to concrete by a man screaming obscenities in my ear. I heard the hiss of a hose and suddenly a high pressure jet of icy water slammed into me.

The jet was so strong it lifted my blindfold and to my horror I saw it was still dark. I’d convinced myself it was about 8am but it was still the dead of night.

My miscalculation devastated me. There were still hours to go. The finishing line was in sight but I was so tired, so addled, I came closer in those moments to quitting than at any other point of the course. I saw no way I could go on.

Melvyn Downes Quality with his wife Zoe and children Amy and Sam – the family live in Dubai

It was precisely at that moment I heard one of our guys being pulled past me, sobbing like a baby. I heard some shuffling and pushing, then sensed that whoever he was had been placed in the stress position.

He’s in a worse state than me, I thought. I wonder who it is? That’s when I got an unmistakeable whiff of salad cream. It could only be Sammy. I thought of his funny sad face, his clown’s tuft of filthy hair. For the second time in 30 minutes I found myself giggling.

Somehow, this was exactly what I needed. No matter how bad I was having it, it was nothing compared to what he was going through.

It wasn’t much, but it was enough to get me through the last stretch of the ordeal. And then it really was over. Just a handful of us had passed. We were told the news in a cold hangar in the same flat, emotionless way all information had been delivered to us over the past weeks. There were no congratulations, no pats on the back.

I looked around at the handful of other soldiers, including, I was pleased to see, Sammy, who’d made it. Every single one of them looked crazy, their eyes enormous and spaced-out, their cheeks hollow.

These defeated, wasted blokes were unrecognisable from the strong, healthy specimens who’d started the course. And yet they were the ones who had passed.

I was too broken to react immediately. It was only later that I felt my spirits soar as, in front of the clock tower at the regiment’s headquarters in Hereford, we were given the sand-coloured berets we’d worked so hard for. I’d made it. The black working-class kid was in the SAS, one of the first British-born black men to join.

It was a dream come true.