The word ‘legend’ is overused. But on Remembrance Sunday, it is worth telling the story of a truly remarkable officer for whom the word barely comes close to honouring a lifetime of extraordinary derring-do.

Over a highly decorated military career spanning nearly half a century, Lieutenant-General Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart built a reputation as, quite simply, the ‘unkillable soldier’ – a man with a relish for warfare who kept fighting despite everything the enemy could throw at him and, in doing so, earned Britain’s most prestigious gallantry medal, the Victoria Cross.

Carton de Wiart survived three major global wars, was wounded more times than he could remember, including being shot in the face, and shrugged off the loss of various body parts – a hand, an eye and part of an ear – as inconveniences.

Rather than retire from the battlefield, he walked straight back in after each new wound had healed, proving a point to his

commanders and fellow soldiers by learning to pull the pin from a hand grenade with his teeth and to reload a revolver with one hand.

Even when not under fire, he was irrepressible. He survived plane crashes, swam into enemy-occupied territory and, undeterred when he was captured in his 60s, tunnelled out of a prisoner- of-war camp.

Such was his reputation for heroism that Evelyn Waugh is reported to have used Carton de Wiart as the model for his character Brigadier Ritchie-Hook, the eccentric fire-eating officer from his Sword Of Honour trilogy.

But his life was far more impressive, and contained significantly more adventure, than any fiction ever could.

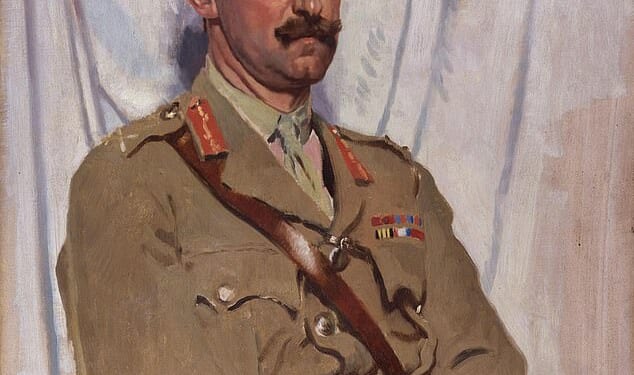

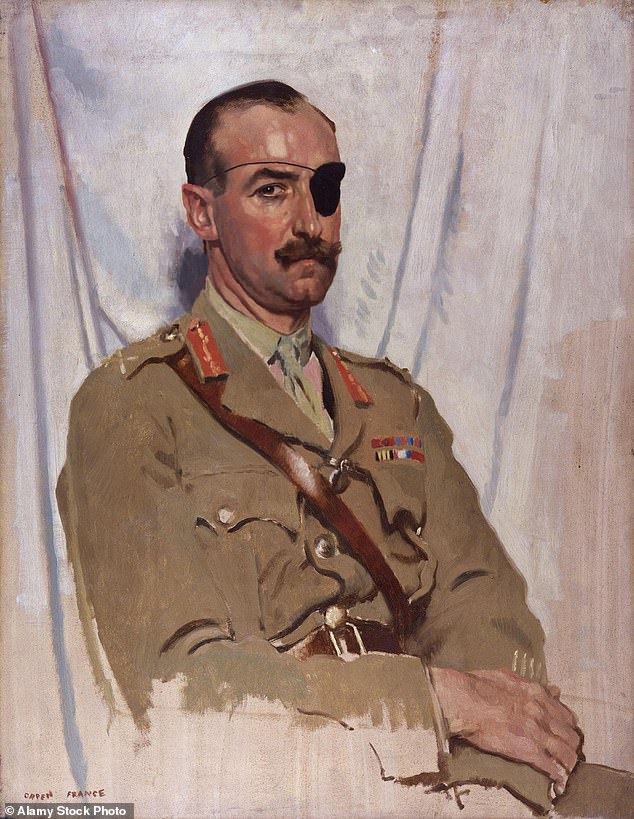

Lieutenant-General Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart (pictured) built a reputation as, quite simply, the ‘unkillable soldier’ – a man with a relish for warfare who kept fighting despite everything the enemy could throw at him

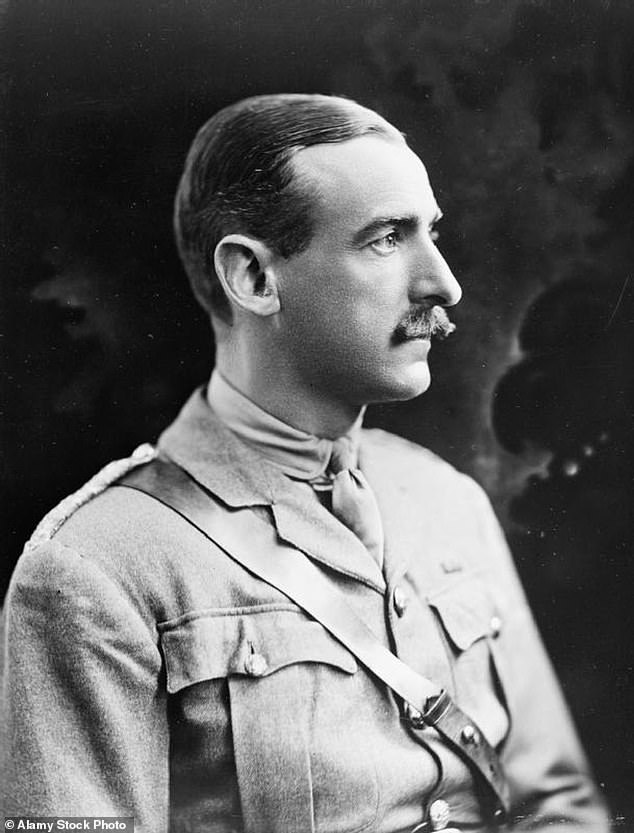

Born into an aristocratic family in Brussels in 1880, he went to Oxford to study law before abandoning his degree to fight in the Second Boer War in 1899.

During the fierce conflict in South Africa, he endured the first of many injuries when he was shot in the stomach and groin.

It required only a temporary pause: sent back to England for medical treatment, he soon returned and was given a regular commission as a second lieutenant in the 4th Dragoon Guards.

Following a period in India, he was naturalised as a British citizen, married an Austrian countess, and was promoted to captain.

But it was in Somaliland in the early days of the First World War that he came by some of his most serious injuries.

In November 1914, a British fort was set upon by the forces of Muhammad ibn Abdallah – leader of the Dervish movement, which sought to free the Horn of Africa from colonial rule – and Carton de Wiart was shot in the face, losing his left eye and part of his left ear.

A comrade, with mild understatement, said that while the agonising incident didn’t stop Carton de Wiart fighting on, ‘his language was awful’. Such resilience earned him the first of many awards for his bravery, the Distinguished Service Order (DSO).

Once again, he found himself back in a London hospital and was given a glass eye for appearance’s sake. But he found it so uncomfortable that he threw it out of the window of a taxi and instead acquired the black eye patch, which would see him frequently described as ‘an elegant pirate’.

The Battle of Cambrai in 1917 where Sir Adrian was shot through the leg, an injury so severe his leg was nearly amputated

Sir Adrian was born into an aristocratic family in Brussels in 1880, he went to Oxford to study law before abandoning his degree to fight in the Second Boer War in 1899

Undaunted, he embarked to the Western Front in February 1915 where, over the next three years, he commanded three infantry battalions and three brigades.

Seven more battle wounds left their mark, including a devastating injury to his left hand in May 1915. When a doctor refused to amputate his fingers, he pulled off two of them and threw them away.

A surgeon removed the whole hand later that year.

In the early days of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916, by then aged 36 and a temporary lieutenant-colonel attached to the Gloucestershire Regiment, commanding the 8th battalion, he was shot again, this time through the skull and ankle.

His ‘dauntless courage’ that day, which had seen him take command when three other battalion commanders were injured and exposing himself ‘unflinchingly’ to intense fire, led to him being awarded the Victoria Cross. His citation said: ‘His gallantry was inspiring to all.’

Following his recovery, he returned once more to the fray, only to become target practice for the enemy. He was shot through the hip at the Battle of Passchendaele, through the ear at the Battle of Arras and through a leg at the Battle of Cambrai, an injury so severe his leg was nearly amputated.

Each time he returned to Sir Douglas Shield’s Nursing Home in London to recover, where he was such a regular, nurses kept a pair of his pyjamas for his inevitable next visit. There is no doubt he was one of the most battle-scarred soldiers in the history of the Army, in part because he believed in leading from the front with his signature rallying cry: ‘Follow me!’

It says much about his character that, describing his Great War experiences in his memoirs, he noted: ‘Frankly, I had enjoyed the war.’

In the early days of the Battle of the Somme (pictured) in July 1916, by then aged 36 and a temporary lieutenant-colonel attached to the Gloucestershire Regiment, commanding the 8th battalion, Sir Adrian was shot again, this time through the skull and ankle

The Victoria Cross awarded to Sir Adrian. Lord Ashcroft is launching a website on Tuesday (Armistice Day) so visitors can take a virtual tour of the exhibition of Victoria Crosses and George Crosses at the Lord Ashcroft Gallery, closed by the Imperial War Museum in September

Once it concluded, he was appointed a CBE and, in 1920, was given the role of aide-de-camp to George V before leading the British mission in Poland as it fought off the Russian Red Army.

But even retirement in 1923 could not restrain his ambitions when the Second World War loomed 16 years later. Then approaching his early 60s, more than twice the age of the average soldier, he headed a campaign in Norway in 1940 and was dispatched to Yugoslavia the next year. But in an astonishing tale of grit and survival, he escaped from the wreck of his Wellington aircraft when it crashed into the Mediterranean off Italian-controlled Libya after its engines failed.

He kept afloat on one of the plane’s wings until it broke in half, which forced him to swim to the nearest shore, while also – somehow – assisting a crew member who had broken his leg in the crash. The land they reached was, of course, enemy territory and the pair were captured by the Italians.

Still, as a prisoner-of-war, Carton de Wiart proved an entertaining companion.

His fellow captive General Sir Richard O’Connor, the 6th Earl of Ranfurly, described him in letters as ‘a delightful character’ and said he ‘must hold the record for bad language’. Remarkably, given his many disabilities, he made five attempts at escape – including seven months spent digging a tunnel – and once evaded recapture for eight days dressed as an Italian peasant, despite not speaking a word of the language. He was finally freed two years later. Sir Winston Churchill, who admired Carton de Wiart as ‘a model of chivalry and honour’, sent him to China to be his personal representative to Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek. He finally retired from the Army in 1947 – after he broke his back in an accident.

Following the death of his first wife, he remarried and settled in Ireland, spending his remaining years fishing and shooting until his peaceful death in 1963, aged 83.

In his autobiography, he wrote: ‘We are told the pen is mightier than the sword, but I know which of these weapons I would choose.’

We will not see his like again.

Lord Ashcroft is launching a website on Tuesday (Armistice Day) so visitors can take a virtual tour of the exhibition of Victoria Crosses and George Crosses at the Lord Ashcroft Gallery, closed by the Imperial War Museum in September. Over coming months, a new website – www.lordashcroftmedalcollection.com – will be developed to include details on all the gallantry medals in Lord Ashcroft’s collection.

Lord Ashcroft KCMG PC is an international businessman, philanthropist, author and pollster. For more information, visit lordashcroft.com. Follow him on X/Facebook @LordAshcroft