‘Have you news of My Boy Jack?’

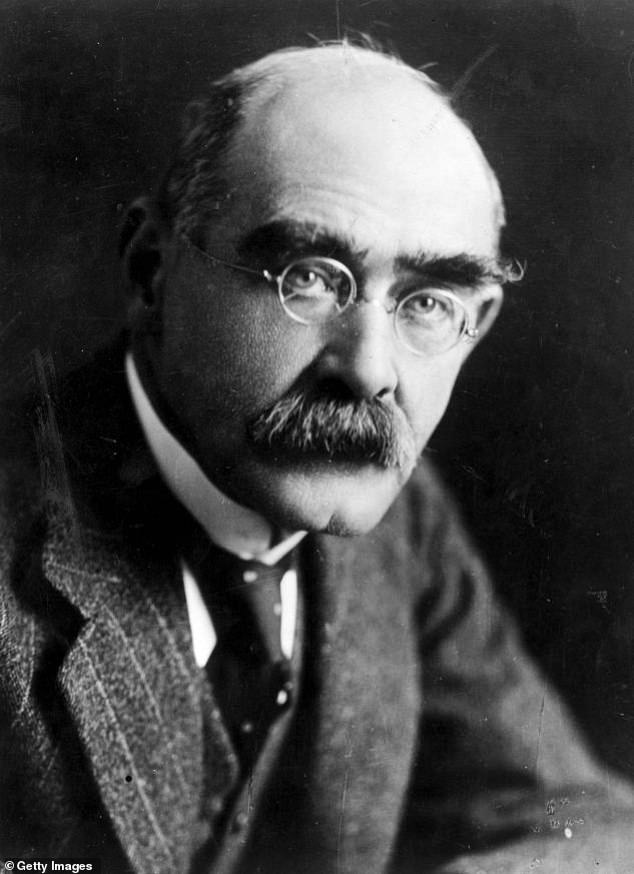

It is the opening to one of the most haunting poems ever written by Rudyard Kipling; penned in 1916 as hundreds of thousands of parents grieved their dead or missing sons amid the ongoing horrors of the First World War.

Now, nearly 90 years on from the The Jungle Book author’s death, letters revealing his torment over his own missing son have come to light.

The patriotic If poet had helped his child, John, to sign up to fight, but he disappeared during the Battle of Loos in 1915, just six weeks after arriving in France.

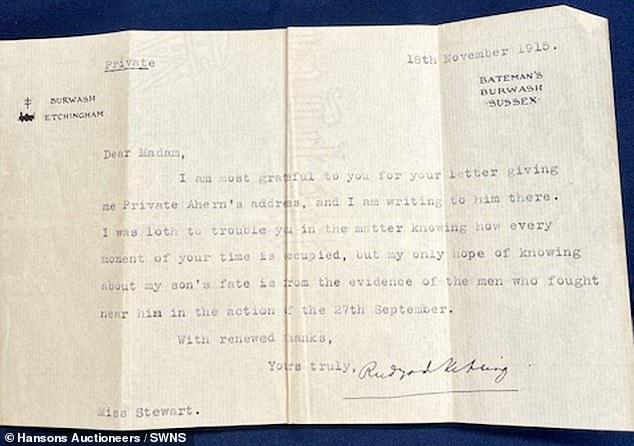

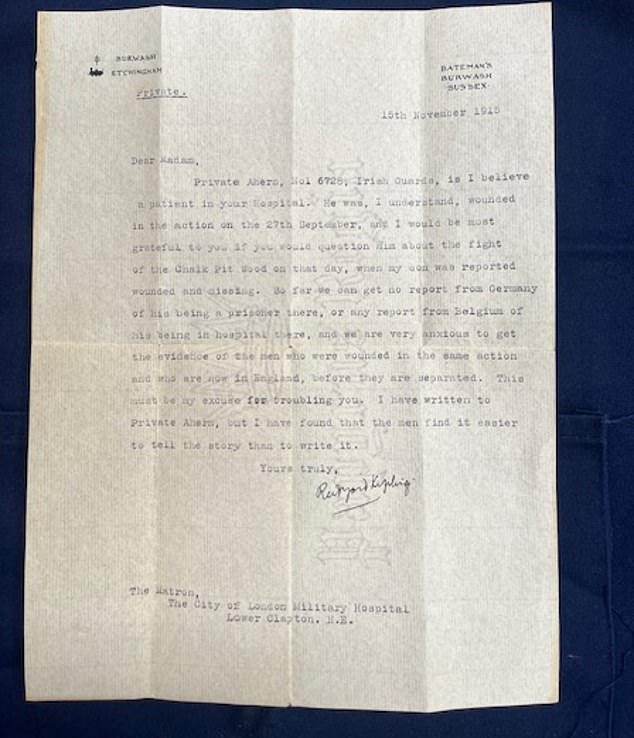

In one of the two letters being sold at auction, Kipling pleads with the matron of a military hospital to ask injured soldiers about the whereabouts of the 18-year-old.

Writing from the family home of Bateman’s in Sussex, he asks if Private Joseph Ahern, wounded alongside his son and recovering in the City of London Military Hospital, may have information.

He says: ‘My only hope of knowing my son’s fate is from the evidence of the men who fought near him on the action of the 27th September.’

In the other typed letter, Kipling writes: ‘So far we can get no report from Germany of his being a prisoner there, or any report from Belgium of his being in hospital there, and we are anxious to get the evidence of the men who were wounded in the same action and who are now in England, before they are separated.

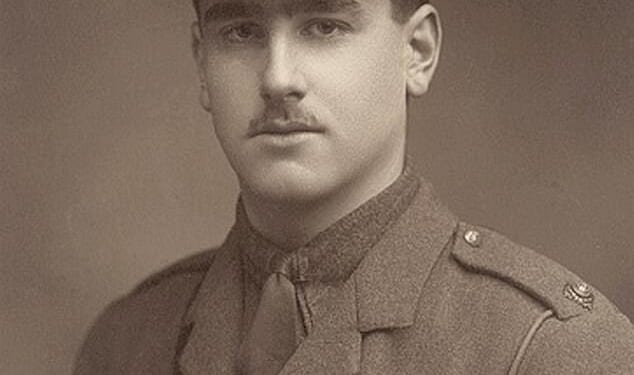

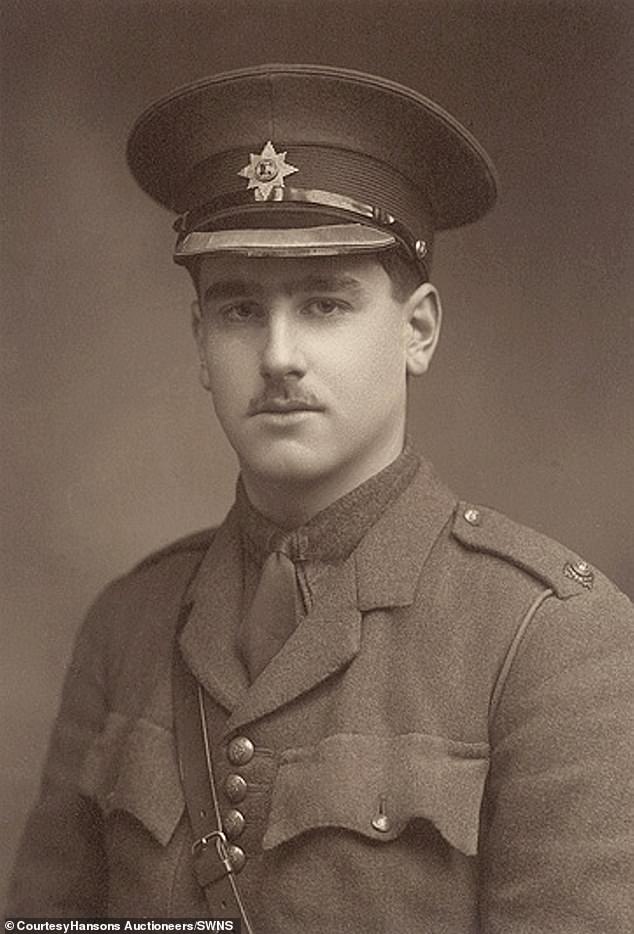

Letters revealing the torment of Rudyard Kipling over his missing son have emerged for sale. Above: Jon Kipling in his Army uniform. He disappeared during the Battle of Loos in 1915

In one of the two letters being sold at auction, Kipling pleads with the matron of a military hospital to ask injured soldiers about the whereabouts of the 18-year-old

‘This must be my excuse of troubling you. I have written to Private Ahern, but I have found that the men find it easier to tell the story than to write it.’

On September 27, 1915, 2nd Lieutenant Kipling went into battle on the third day of the Battle of Loos, dubbed the ‘Big Push’.

The young soldier was wounded and subsequently declared missing as his Irish Guard battalion advanced towards Chalk Pit Wood.

In 1916, the army officially declared John dead, though his body had not been found.

In 1919, the body of an unidentified Irish Guards lieutenant was discovered on the battlefield, and was buried in an anonymous grave at St Mary’s Cemetery.

Then, in 1992, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission changed the description on the gravestone to read John Kipling.

The move led to a huge debate over whether the grave really contained Kipling’s son.

Research in 2016 concluded that the remains are those of the John Kipling.

In the other typed letter, Kipling writes: ‘So far we can get no report from Germany of his being a prisoner there, or any report from Belgium of his being in hospital there, and we are anxious to get the evidence of the men who were wounded in the same action and who are now in England, before they are separated. This must be my excuse of troubling you

The correspondence is expected to make £800-£1,200 at Hansons Auctioneers in Etwall, Derbyshire, on October 9.

The letters have been unearthed after originally being acquired by London collector and builder Cecil Johnson in the 1950s.

His grandson, who lives in Derbyshire and doesn’t want to be named, inherited them from his mother.

He said: ‘My grandfather was a wheeler dealer and a bit of a Del Boy.

‘But he had a lot of money and was a frequent visitor to London auction houses which is how he might have acquired them.’

Hansons Auctioneer’s Karl Martin added: ‘These letters are deeply personal and a great insight into the torment of a father desperately seeking information about his son.

‘Guilt might have played a part. Kipling, who was in favour of the war, helped facilitate his son’s commission with the Irish Guards after his poor eyesight made him ineligible for military service.

‘Knowing the casualty rate, Kipling might have known he was signing his son’s own death warrant.

Kipling died in 1936 after turning from a supporter of the war to a devoted critic

‘But he and wife Carrie thought it essential to prevent a German victory.’

Kipling also feared his pro-war stance meant his son, if captured, might face a hash imprisonment.

It was the second time that he and his wife had lost a child. In 1899, their eldest daughter Josephine died from pneumonia at the age of six.

Kipling’s poem My Boy Jack was explicitly written for Jack Cornwell, who was awarded the Victoria Cross after being killed aged 16 while serving on Royal Navy ship HMS Chester during the Battle of Jutland.

However, it is widely accepted that the poem’s verses echo is own anguish at his missing son.

His grief was dramatised in the 1997 play My Boy Jack, which was adapted into a TV film starring Daniel Radcliffe in 2007.

Kipling went on to pen the similarly haunting poem Common Form, which reads: ‘If any question why we died / Tell them, because our fathers lied.’

He died in 1936 after turning from a supporter of the war to a devoted critic.