The village of Ardleigh in Essex doesn’t look like a battlefield. The sun is glinting off the clear waters of its reservoir, the birds are in full song and a canopy of oaks is closing over the single-track lanes.

But this community is on the front line of a war.

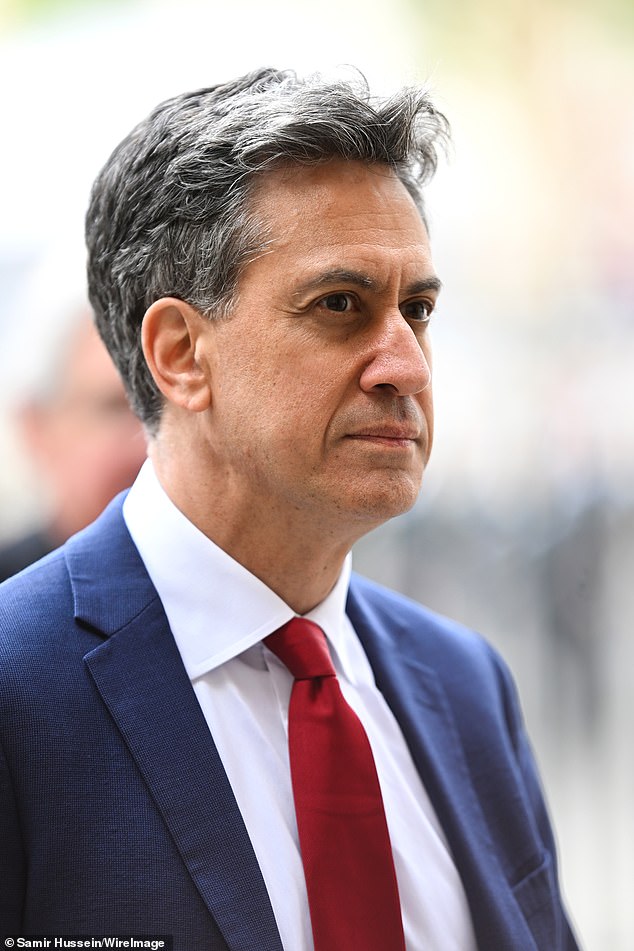

If Ed Miliband and National Grid get their way, Ardleigh will soon be scarred by a line of 160ft electricity pylons on one side and a 400ft-wide trench for cables on the other.

No fewer than three electricity substations are to be built in this one parish – which is mentioned in the Domesday Book – along with an enormous ‘interconnector’, a four-storey plant that enables the UK to export and import electricity to and from continental Europe.

As for those idyllic lanes, currently waist-high with cow parsley, they’ll see about 550 heavy goods vehicles driving down them every day as construction starts on this project – part of what National Grid is styling Britain’s ‘Great Grid Upgrade’.

Under the £16 billion scheme, launched in April 2023, 625 miles of ‘pylon highways’ will be laid stretching from Grimsby in Lincolnshire to Walpole, near King’s Lynn in Norfolk.

There’s also Chesterfield to Willington in Derbyshire and a stretch from East Yorkshire to High Marnham, Nottinghamshire. The line threatening Ardleigh runs from Norwich to Tilbury in Essex.

There are 17 major projects like these – plus additional plans by green energy companies to build miles and miles of smaller pylons connected to onshore wind farms, such as those atop mid Wales’s gusty hills.

Dystopia: The view for Ardleigh residents could soon be akin to that of Dungeness power station on the Kent coast

If Ed Miliband and National Grid get their way, Ardleigh will soon be scarred by a line of 160ft electricity pylons on one side and a 400ft-wide trench for cables on the other

In Ardleigh, the residents are furious. Jayne and Bruce Marshall could lose 80 per cent of their farmland.

For Gilly and Paul Whittle, it means their £1.5 million house is likely to be halved in value, if it can be sold at all.

The local vineyard, with its fashionable Skylark café, will have a pylon slap-bang in the middle of a view which is today positively Provencal.

And Benson’s Stud might have to close its doors, unable to give its multi-million-pound racehorses the peace and quiet they need.

Could this, in turn, affect the string of Royal mounts stabled by the King at nearby Newmarket? Stud owner Ben Wallis is too discreet to say.

What’s clear is that, unless the 15th-century church of St Mary (itself about to be encircled by a forest of pylons) has a 21st-century miracle to offer, Ardleigh is going to be changed for ever: collateral damage in the country’s race for renewables and the controversial net zero ambitions of Mr Miliband, the dogmatic energy secretary.

Not that the village is going down without a fight. Nor are the hundreds of communities elsewhere in England, Scotland and Wales now threatened by the march of the pylons.

Around the country, an anger is growing, the like of which have not been seen since the campaign against HS2, the wildly expensive high-speed rail link that threatens to wreak similar devastation on Britain’s dwindling green spaces.

Horror: Jayne and Bruce Marshall could lose as much as 80 per cent of their farmland

In Westminster, the row is now at boiling point.

Earlier this month, Sir Tony Blair publicly turned on Mr Miliband and his radical eco-schemes – describing net zero as ‘doomed to fail’. Labour-backing union barons of GMB and Unite are similarly pessimistic.

Meanwhile, Rosie Pearson, founder of the Essex Suffolk Norfolk Pylons action group, says: ‘Ed Miliband is an ideologue, a zealot. He has a ridiculous political deadline to meet and he doesn’t care how it’s achieved.’

‘The last government was listening, this one isn’t. There’s no interest in doing things in a way that means the upgrade to our energy infrastructure has lower community impact, lower social impact and less natural capital [countryside] impact – and actually lower bills as well.’

Mr Miliband has labelled such criticism ‘old nonsense and lies’, calling the people who oppose him ‘obstructionists’.

Ardleigh resident Gilly, 66, begs to differ. She says: ‘I’m not a Nimby or a nay-sayer as Keir Starmer’s government would have everyone believe. Nobody disputes the need for more electricity. But we are rushing into these pylon plans for the sake of a political deadline.’

She and her husband Paul, 75, have lived in their Grade II-listed home for 37 years. They were about to downsize when it became clear that soon four or five pylons would tower over their back garden.

‘We had a surveyor out for an informal chat last week. He advised that the value of our house would be cut by at least a third, probably in half, if anyone would buy it at all. I mean, why would you?’

Recent research from property consultancy Allsop showed a so-called ‘pylon penalty’ on the value of homes as far as 500 yards from a power line.

Dismay: Paul Whittle fears his home, worth £1.5 million, is likely to be halved in value

In Birmingham, pylon-blighted houses were selling for 23 per cent less than the city average.

For country properties, the damage is even worse, making a mockery of Mr Miliband’s pledge to give householders near his beloved new infrastructure a derisory £250 off their bills per year.

Two miles down the road from Gilly and Paul’s house in Ardleigh lies a vineyard newly cultivated by Robert Blyth, 42, and his sister Rosie Forshaw, 44.

In 2016, the siblings, who run their family farm diversified into wine, turning ten acres of their land over to Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier and Chardonnay grapes.

They grow enough for 30,000 bottles a year, sold under the Prettyfields label. Ironically, their vineyard was named after the adjacent Pretty Field, which will soon host another pylon – one of four or five on the family’s land.

Robert’s worries are manifold: how to farm around the pylons; damage done to the soil; the destruction of mature oaks and the mixed hedgerows which are home to stoats and badgers, red kites, bitterns and bats.

‘As for the vineyard, what’s an industrial construction project going to do to soft fruit?’ he asks.

We have met in the Skylark café, which overlooks their grapes. The thriving business is tenanted by Matt Wilsher who has spent the past three years turning this bucolic spot into a commercial enterprise: it’s a farm shop, microbrewery and community hub.

Worry: Robert Blyth and Rosie Forshaw’s vineyard will be impacted

‘National Grid don’t care about me and whether my business can survive this,’ says Matt.

‘I am angry, bitter and afraid for the future. If they would only look at my business and all the others like it then it would give a much clearer idea of the true cost.’

Many would prefer the electricity cables necessary for the grid upgrade to be buried (known as ‘undergrounding’). But National Grid maintains that this can be five to ten times more expensive than stringing them up on pylons.

Such figures are disputed by campaigners who say the company fails to account for the cost to homes, tourism, agriculture, landscapes and rural enterprises.

To be clear, no one disputes that Britain needs more electricity. In the UK, demand is predicted to rise by 50 per cent in the next five years and to double in the next 25.

That’s a lot of wind and solar energy to plug into a grid largely developed in the last century, created to serve Britain’s coal-fired power stations, not windfarms in the North or Irish Seas.

Last month, five Welsh farmers involved in a court battle to stop the pylons in their local area surrendered in the face of legal fees starting at £30,000 each and the risk of a criminal record.

‘We were screwed,’ said Wynne Jenkins, 71 of Llanarthney in Carmarthenshire.

A sign on a tree near Louth in Lincolnshire protesting against the controversial pylon plans

There were slow hand-claps and shouts of ‘Shame on you!’ as energy executives and their expensive legal teams filed into Llanelli Magistrates Court to fight the farmers.

In Westminster, Mr Miliband is facing similarly furious opposition. A growing army of critics believe his plans are wrong-headed, threatening to turn the UK into ‘Pylon Island’. Moreover, they say the sums don’t add up.

Last year an official report into the transmission system in East Anglia concluded that burying cables could prove £600 million cheaper than erecting pylons on the Norwich to Tilbury route.

The caveat was that, even if it started now, National Grid would have to wait until 2034 for the project, meaning the Government would miss its arbitrary 2030 deadline for ‘decarbonising’ the grid.

Shadow Defence Secretary and South Suffolk MP James Cartlidge says: ‘The report shows that you can wait until 2034 and still have what is a very competitively priced option that doesn’t lead to permanent damage to the countryside.’

Ardleigh’s own MP, Tory Sir Bernard Jenkin, couldn’t agree more, asking why cables have to run above or below fields in the first place. Instead, he insists, they could be run offshore.

‘In this country, we are lucky to have the seabed as an alternative. Let’s use it!’ he demands.

But while Mr Miliband remains at the helm of Britain’s energy policy, it seems likely that work on the Ardleigh section of the Great Grid Upgrade will break ground in 2027 as planned.

Mr Miliband has labelled criticism as ‘old nonsense and lies’, calling the people who oppose him ‘obstructionists’

‘We’re cannon fodder,’ says Ben Wallis of Benson’s Stud.

‘The Government has no clue about the damage it will do to the rural ecosystem. About 25 per cent of my land will be affected and that directly impacts on me and my son Charlie.’

He doesn’t know what the future holds for him. Nor is there much confidence over at Spindles Farm.

‘It’s our job to feed people,’ says 62-year-old Jayne Marshall. ‘We’ve spent our lives doing it.

‘Given the amount of conflict in the world, Britain’s food security is dire and this is no time to be hurrying towards net zero. This could be the end for us.’

We are speaking in the orchard where she grows Golden and Red Delicious and Bramley apples. In the distance there’s an alder hedge where red kites perch, oaks that are home to a pair of barn owls and, nearby, a meadow seeded with wildflowers to nourish turtle doves.

The scene exemplifies how Ardleigh got its name – it comes from the old English ‘leah’ meaning clearing. It’s still rustic. For now.

But another five years spent on this Government’s planned trajectory and it won’t be, not with a 680-acre land-grab for pylons and substations, plus the interconnector hooking it all up to Germany.

‘There are better ways of transmitting and distributing electricity,’ sighs Dr Jonathan Dean from The Campaign for the Protection of Rural Wales. ‘But the better ways are being ignored. And we’re still not asking the real question which is this: what is a price worth paying?’