The Criminal Cases Review Commission operates from a ten-storey office block overlooking the gleaming, space-age facade of New Street station in central Birmingham.

It was opened in July 2022 by then government ‘efficiency’ minister Jacob Rees-Mogg under what he called ‘plans to create a leaner and more efficient public estate’ by relocating civil servants from London to the regions.

The Commission, whose 113 employees carry out the critical role of identifying potential miscarriages in our justice system, is one of 20 quangos and government departments that moved into the ultra-modern facility that year.

Ever since, staff have been able to enjoy what its website calls ‘comfortable breakout areas, a well-stocked communal kitchen, and great access to transport links and city life’.

That’s the theory, at least. But the reality is quite different. For on an average day, those swanky ‘breakout areas’ and kitchens are weirdly empty.

To blame is one highly controversial fact: Five years after Covid, the organisation, which is better known as the CCRC, continues to let employees work entirely from home.

Most staff show up to HQ just ‘once or twice a year, on average,’ it admits, saying the only ones required to venture into the building on a regular basis are members of the IT department, plus a presumably under-employed receptionist.

Even chief executive Karen Kneller, a lawyer who received a £130,000 salary from taxpayers last year, plus £34,000 towards her pension, rarely bothers to cross her expensive building’s threshold.

Karen Kneller, chief executive of the Criminal Cases Review Commission, received a £130,000 salary from taxpayers last year, plus £34,000 towards her pension, yet rarely bothers to cross her expensive building’s threshold

‘I am probably in the office maybe one or two days every couple of months or so,’ she blithely admitted to a (gobsmacked) committee of MPs last month.

This despite Kneller living with her husband Mark Etchells in a semi-detached house in Handsworth – a mere 15-minute drive from the office she so rarely visits.

If the CCRC’s role was of limited importance, or if Mrs Kneller, 61, and her staff were doing a semi-competent job, such loose working practices might be vaguely defensible.

But in fact, the opposite is true.

On the first count, the organisation is of course very important indeed. It plays a crucial role in upholding faith in Britain’s criminal justice system by reviewing contested cases in search of wrongful convictions.

Among the various (seriously) hot potatoes it is currently juggling is the thorny question of whether to return Lucy Letby’s case to the Court of Appeal.

On the second count, regarding competence, Kneller stands on even stickier ground.

For those MPs she spoke to last month, who sit on Parliament’s Justice Committee, published an explosive report yesterday saying the organisation not only requires ‘root and branch reform,’ but that its chief executive’s position is no longer ‘tenable’.

Last week, we saw a case in point when Peter Sullivan, pictured, known as the so-called ‘Beast of Birkenhead’, walked free after spending an astonishing 38 years behind bars for a crime he didn’t commit

The MPs were, if anything, understating things. For this powerful quango, which chews through almost £10 million of public money a year, has in recent years become a byword for chaos and dysfunction.

A glance under the bonnet reveals that its 50-odd Peloton-riding case workers are permitted not just to work remotely, but also to choose when they will actually be ‘on duty’, thanks to an absurdly liberal ‘flexi-time’ policy. This inevitably and frequently places them at the coal-face at different times of the day from colleagues and team members.The net result, critics say, is that it can take years to deal with even straightforward cases, leaving wrongly convicted victims to twiddle their thumbs in jail.

Meanwhile, a series of high-profile blunders have lately seen Kneller’s Commission blamed for contributing to some of the most grotesque miscarriages of justice in modern British history. Only last week, we saw a case in point when Peter Sullivan, the so-called ‘Beast of Birkenhead’, walked free after spending an astonishing 38 years behind bars for a crime he didn’t commit.

A vulnerable man, who suffers from learning disabilities, Mr Sullivan had been wrongly convicted of the brutal sexual assault and murder of a 21-year-old barmaid in 1986.

He’d always protested his innocence, and his legal team had told the CCRC in 2008 that DNA analysis of a semen sample found on the victim would exonerate him.

But while a forensic technique called ‘Y-STR’, which allows such analysis, became available in 2013, the Commission waited until 2021 to order proper tests. Even then, it would be another four years before he was acquitted.

Lord Falconer, the former Justice Secretary, described the Commission as ‘unled and generally regarded as useless’ in the wake of Mr Sullivan’s acquittal.

Lord Garnier, a former Tory Solicitor General, told an interviewer that the organisation was in ‘a state of complete collapse’ and needs ‘gripping’ by the Government.

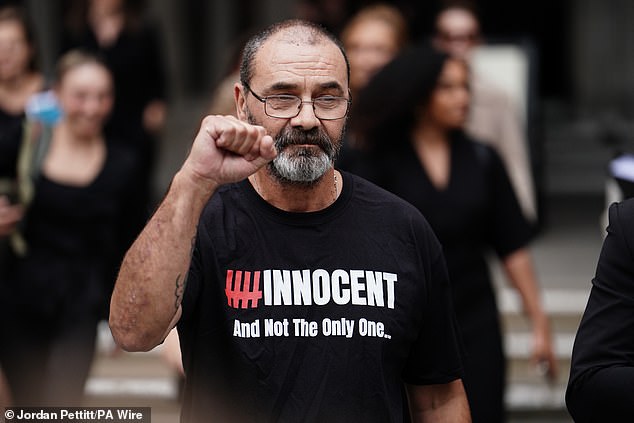

Andrew Malkinson served 17 years for a rape he didn’t commit before his conviction was finally quashed in 2023. A formal inquiry into the Commission’s calamitous handling of the Malkinson case, by a KC named Chris Henley, was published last year.

Friends of Victor Nealon, who was wrongfully convicted of attempted rape and spent an additional ten years in prison because the CCRC again refused to carry out basic DNA tests that would have proved his innocence, would presumably agree.

As would Andrew Malkinson, who served 17 years for a rape he didn’t commit before his conviction was finally quashed in 2023.

He and his legal team had spent more than a decade pleading with the CCRC to conduct DNA tests on samples taken from the victim, which he steadfastly maintained would prove his innocence only to meet with obfuscation and refusal. Had staff done their job properly, Mr Malkinson would have been released at least a decade earlier.

A formal inquiry into the Commission’s calamitous handling of the Malkinson case, by a KC named Chris Henley, was published last year.

It exposed a catalogue of appalling blunders, missed opportunities and shabby work by the quango, whose caseworkers exhibited ‘muddled’ thinking, ‘poor’ analysis and language that was ‘casual and dismissive’.

Their work ‘lacked purpose’ and was ‘left drifting for many months’ by superiors who didn’t bother to read evidence, Mr Henley found.

Importantly, the CCRC’s ‘head of casework’ at the time of both its ‘very poor’ work on Mr Malkinson, and Peter Sullivan’s first approach to the organisation, was its current chief executive, Karen Kneller. A public sector ‘lifer,’ qualified barrister, and enthusiastic quangocrat, she has spent three decades on the government payroll, including about 20 years at the CCRC and juggles her current role with a host of side jobs. They range from a non-executive directorship of University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Trust, a trusteeship of homeless charity Shelter, and a role chairing an equalities charity calling itself a ‘think fair tank’ named Brap.

All this, and more, contributed to a car-crash appearance by Kneller before the Justice Committee in Parliament last month, at which her at times woeful efforts to defend the organisation’s culture met with disbelief from MPs.

Things got off to a bad start when the chief executive was asked whether she’d yet bothered to apologise to Mr Malkinson for the ten extra years he spent behind bars thanks to the CCRC’s obvious incompetence.

‘No, I haven’t,’ she glibly responded. ‘Do you think it might be appropriate to pass on that apology now?’ asked an MP. ‘Yes, absolutely,’ she conceded.

There followed a surreal exchange in which Kneller umm-ed and ah-ed that the CCRC is ‘not an office-based organisation any more’, and attempted to argue that this was absolutely fine because it allowed it to recruit talented staff from all over the country.

Andy Slaughter, the Labour MP who chairs the Justice Committee, gave that line short shrift, claiming there was a ‘hole in the heart of the organisation’ and concluding: ‘I cannot believe you are the only organisation in the country that has not come out of Covid yet.’

Elsewhere in the extraordinary meeting, Kneller attempted to defend her generous remuneration (she was handed a 7 per cent pay rise and a bonus of £8,000-£10,000 just a month before Mr Malkinson was exonerated, and in the 2023-24 financial year enjoyed another 9 per cent rise) by saying she was ‘not privy’ to discussions about her salary.

Perhaps most importantly of all, she was then asked to defend the organisation’s response to Mr Henley’s excoriating report.

The KC’s document turns out to have been submitted in January last year. But it wasn’t published for six months, during which the CCRC, which already has a large taxpayer-funded press office, paid an external PR consultant £14,000 to advise them on how to manage the inevitable fallout.

Several reports have suggested that the CCRC spent that period attempting to water down some of the report’s findings, lobbying Mr Henley to ‘soften’ his criticism of senior employees.

Asked whether such skulduggery had occurred, Kneller issued a vigorous denial, insisting to MPs that much of the delay was instead entirely due to ‘typographical errors and some factual issues’ with the report’s findings.

However, Mr Henley appears to remember things differently, and this week publicly insisted that Kneller’s claim is completely false. He told the Sunday Times: ‘Karen Kneller misled Parliament. Her answers to the select committee were thoroughly inaccurate.’

The Justice Committee agrees, with that assessment describing her evidence to them as so ‘unpersuasive’ that ‘we no longer feel it is tenable for her to continue as chief executive’.

‘I don’t see how she has any credibility or authority to stay in the role,’ says Neil Shastri-Hurst, a Conservative member of the body. ‘This is such an important job that to not have a grip on it, which is what we have found, is unforgivable.’

Interestingly, the CCRC did not respond when I asked if they were standing by the Chief Executive, saying only that they intended to ‘note’ the Committee’s recommendations. Among their pressing tasks will be to finally elect a CCRC chair – preferably one who is prepared to work full time.

The previous incumbent, quangocrat Helen Pitcher, was forced to resign in January after Justice Secretary Shabana Mahmood said she was ‘unfit’ to do the job, after being singled out for criticism by Mr Henley.

Pitcher was being paid £95,000-a-year to work two days a week, juggling the role with eight other jobs, including a non-executive directorship of United Biscuits and a seat on the Judicial Appointments Commission, where she earned another £55,000-£60,000 for working two days a week. She continues to do that role (which critics saw as being in conflict with her duties at the CCRC) to this day.

Unlike most CCRC colleagues, who are banned from working on cases when overseas, Pitcher also spent vast amounts of time in Montenegro, where she ran a villa rental company named ‘Perast Paradise Properties’.

In fact, when the CCRC was thrown into crisis, following Mr Malkinson’s acquittal in 2023, its part-time chair could be found on Instagram posing in bare feet on a boat outside a local mussel bar, boasting to her social media followers that she was ‘having an amazing time’.

Elsewhere, Pitcher has also been president of the ‘directors network board’ at Insead, the elite business school outside Paris.

At the time she held the position, her then colleague Kneller spent tens of thousands of pounds of the CCRC’s cash attending various courses at the institution, frequently staying at its in-house four-star hotel The Ermitage, which boasts a terrace bar overlooking the Fontainebleau forest, a fitness centre, treehouse bar and squash courts.

Quite why such a keen advocate of ‘remote’ working felt the need to attend such a grand venue in person is anyone’s guess, but the revelation, first reported by The Guardian newspaper in February, added to the sense of chaos around Kneller’s tenure.

All of which represents a shameful and shabby state of affairs for an organisation founded with the best of intentions in the 1990s, in the wake of several high-profile miscarriages of justice, including the cases of the Guildford Four and Birmingham Six.

In its early days, the CCRC’s 60 members of staff included a range of people experienced in exposing miscarriages of justice, including retired senior policemen.

Among the 12 commissioners (of which three are needed to sign off a referral to the Court of Appeal) was David Jessel, presenter of the TV series Trial And Error, which helped overturn several convictions.

He was joined by the forensic psychiatrist James MacKeith, who greatly contributed to the eventual quashing of the convictions of the Guildford Four in 1989 by proving evidence had been falsified and suppressed by police.

Each was employed on a full-time basis, and expected to attend head office every day, where the work was carried out in a collegiate fashion. In return, commissioners were paid (for the time) a hefty salary of close to £90,000. Today, they are by contrast paid a daily fee of a few hundred pounds and largely work part-time. It’s perhaps little surprise that three of the 12 roles are currently vacant. For most of the 2000s, the CCRC largely escaped public criticism. But in legal circles, there was growing hostility about both the length of time staff were taking to consider cases, and their apparent reluctance to send cases to the Court of Appeal, with only roughly 3 per cent being referred.

In 2015, the Justice Committee said the organisation ought to be ‘less cautious’ in taking such steps, but the following year its referral rate fell to a mere 1 per cent. By then, Karen Kneller had been chief executive for three years.

Questions were beginning to circulate about the calibre of staff the organisation was attracting, along with their work ethic.

In 2018 a BBC Panorama investigation entitled Last Chance For Justice shared internal documents stating that case review managers were ‘struggling to cope’.

The programme found minutes from a meeting in which a commissioner said they ‘doubted whether the work required to uncover certain miscarriages of justice was now being done’.

The commissioner ‘worried about a culture where staff believed finding new evidence was actually seen as troublesome because of the work involved’.

Back then, the Commission (which covers England and Wales, but not Scotland) boasted 90 staff and a £5 million annual budget. Today, the size of its workforce has increased by a quarter, while its spending has doubled. But lawyers dealing with the organisation believe standards have continued to fall, particularly in recent years. Many blame the advent of so-called ‘home working’.

‘To do their job properly, CCRC staff need to be discussing things all the time and rubbing shoulders and bashing things around,’ says Matt Foot, of the charity Appeal, which represented Mr Malkinson. ‘But they are never in. I find the whole thing quite bizarre.’

Glyn Maddocks, a KC who has successfully represented many victims of miscarriages of justice, tells me: ‘It’s outrageous. You can’t do that sort of job remotely. It’s an absolute nonsense.

‘People need to be in the office, sitting in the meeting room with colleagues who have experience, discussing what to do next. The whole thing is a farce.’

Mr Maddocks recently represented a man named Oliver Campbell, who in 2024 overturned a historic murder conviction. His victory followed a 24-year campaign which had initially seen the CCRC give his application short shrift.

‘Given that experience, and what we now know about the shoddy job they did on Malkinson, you wonder how many other cases they’ve been incompetent with over the past 28 years,’ adds Mr Maddocks.

MPs agree. But the CCRC’s annual report offers an insight into the culture of unaccountability that prevails among its deeply unimpressive top brass.

Larded with management speak, wokery and irrelevancies (in the opening pages, it declares that 37 members of staff are male, 76 female, 19.5 per cent hail from an ethnic minority, and 20.8 per cent have a disability) this document uses the introduction to outline its top ‘strategic priorities’.

Number one on the CCRC’s list is ‘people, being an employer of choice’. Or, to put things another way, making sure that members of staff are happy.

For an organisation whose raison d’etre is supposed to involve overturning grievous miscarriages of justice, this feels like an odd thing to categorise as a top priority. But like many a public sector organisation before it, the Criminal Cases Review Commission increasingly seems to place the interests of its bloated workforce above those of the public they supposedly serve.

Exhibit A, on this front, is its overpaid, under-competent, homeworking CEO. She was last night still refusing to fall on her sword. And so this grotesque scandal continues.