This article is taken from the June 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

In the introduction to Nothing if Not Critical, published in 1990, the great art critic Robert Hughes laments how the traditional techniques of painting that had been passed down from the 16th century were no longer taught.

He writes “virtually all artists who created and extended the modernist enterprise between 1880 and 1950, Beckmann no less than Picasso, Miró and de Kooning as well as Degas or Matisse, were formed by the atelier system and could no more have done without the particular skills it inculcated than an aircraft can fly without an airstrip”. But from the 1950s, the traditional techniques began to die out in art schools. Art became untethered from its roots, resulting in the banal chaos of much contemporary art that Hughes abhorred.

Now, in the manner of a trendy vicar starting a sermon with a news story and then linking it to Jesus Christ, I will try to apply Hughes’ insight to wine.

Once upon a time, middle-class British wine lovers would have had a good knowledge of the vinous equivalent of the old masters. These are the Bordeaux first growths; Haut-Brion, Margaux, Lafite, Latour, Mouton and d’Yquem in Sauternes plus Cheval Blanc and Petrus on the right bank. Whilst you wouldn’t try them often, you would be familiar with such wines, and probably have some in your cellar.

Historically the first growths would normally cost about a third more than lesser clarets such as Château Talbot. The 1960s in particular would have been a great time to be a claret lover, as many grand houses were forced to sell off their cellars to pay death duties.

In the 1970s and ’80s prices began to rise as Americans, Germans and later the Chinese began buying wines that had hitherto been mainly consumed in Britain. This led to the situation in Dirty Rotten Scoundrels where Steve Martin’s character quips, “So you got a lot of wine to drink,” to which fellow conman played by Michael Caine replies, “You can’t. They’re far too valuable.”

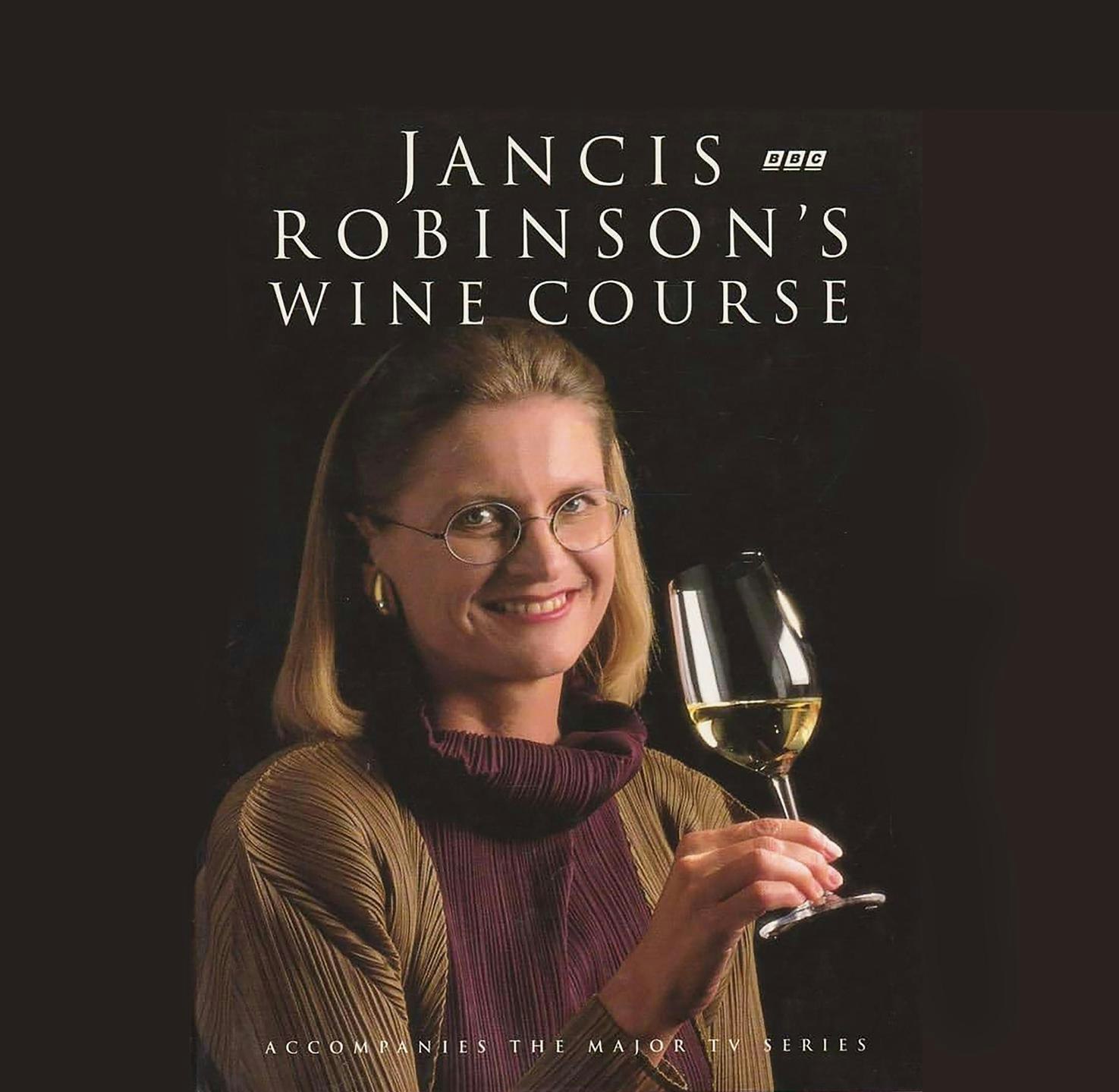

But things had barely got started when that film was released in 1988. In Jancis Robinson’s 1991 BBC series Vintners’ Tales, there’s much hullabaloo at a Mouton 1970 costing £800 a case — about £66 a bottle. A Mouton of similar age and quality will now cost you about £700 a bottle. In 2004, the year I joined the Wine Society, Cheval Blanc 1996 would have set you back £120. A recent vintage is now nearer £600.

Meeting a fellow oenophile in the 1970s, ’80s or even ’90s would have involved, I like to imagine, much bonding over how the ’61s are coming on. But today unless you are either very rich, have some generous friends or work in the wine trade, you will never have an opportunity to try such wines.

My knowledge of the greats is limited; I hope Critic readers don’t think me a fraud. I have tried Lafite twice, Mouton Rothschild only once (but it was the glorious 1996 drunk in 2014), d’Yquem on a few occasions, but I’ve never tasted Haut Brion or Latour.

As for Petrus and Cheval Blanc, not a chance. I’ve had a bit more experience further down the ladder, including on one memorable occasion the 1982 and 1986 Léoville Barton drunk over lunch with the late Anthony Barton.

Collectable wine used to mean Bordeaux. Older wine books would be at least half French with chapters on Germany, sherry and port. The rest of the world was “here be dragons” territory. Today there’s too much choice. When even Essex is producing convincing Burgundy-style wines, it’s becoming impossible to keep up.

It’s like the difference between having three channels on television and all those streaming apps my daughters insist I pay for. The classical, essentially Bordeaux, models for wine are being abandoned.

Hence the rise of bizarre cloudy wines that smell like scrumpy but cost £12 a glass in a trendy Peckham restaurant or the sweet red wines that are becoming increasingly common in supermarkets.

Today wine lovers are talking past each other. We are losing our shared frame of reference. At one time an educated Englishman would have read the same books, learnt the same history, known his classics, some Latin and Greek, sung the same hymns and known the same wines.

In the end, it doesn’t matter quite so much whether people know the same wines if they have no knowledge of their country’s history, art and literature, but it is another loss of our shared culture. The good news is that first growth Bordeaux is not the blue-chip investment it once was.

If you’d bought Latour 2010 when it was first released, you would have lost money. Let’s not get carried away; we are still talking about £8,000 for a case of 12. But the price of mid-range claret is currently absurdly low. I’ve spotted Château Mauvesin-Barton 2018, made by the team at Léoville Barton, for around £25. Or from the nearby Château Poujeaux, Lea & Sandeman has the excellent 2016 for under £40.

At these prices can you afford not to be drinking Bordeaux? Who knows, maybe the top stuff will continue to slide so that we can enjoy a Latour or Lafite on high days and holidays.