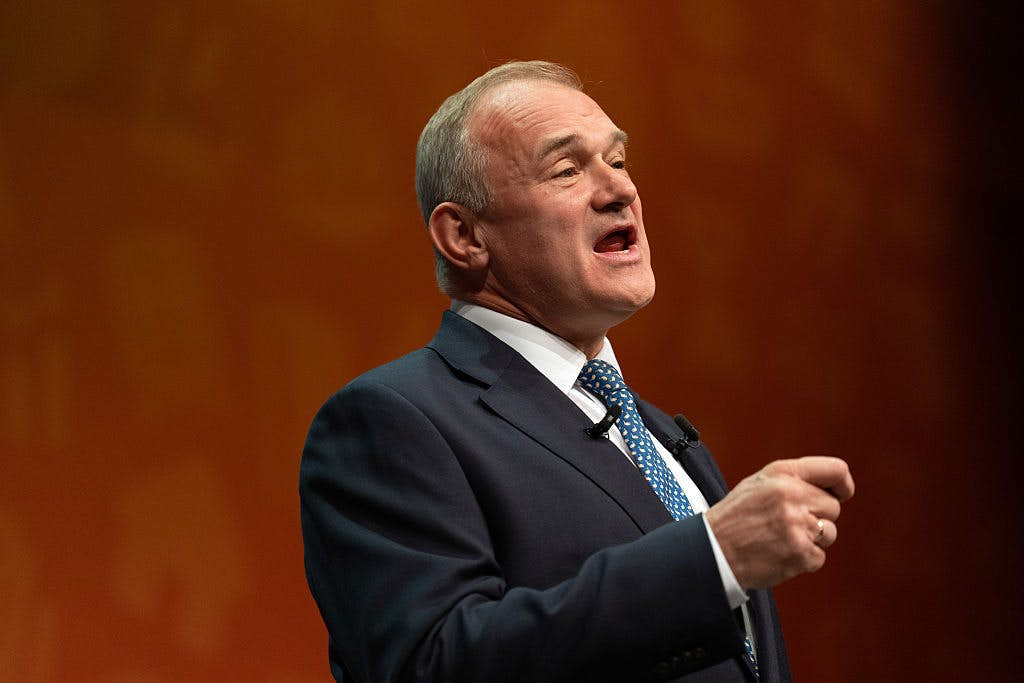

Who’s scared of the United States? It isn’t Ayatollahs preaching in madrassas, terrorists lurking in caves, or dictators plotting in war rooms who were worrying over the prospect of the Great Satan this week — no, it was Ed Davey at the Lib Dem Party Conference. Craft ale consuming dads in John Lewis jumpers convened in Bournemouth to (metaphorically) burn the Stars and Stripes. What on earth is going on?

As I’ve written before, many Britons struggle to understand our transatlantic cousins. Like children with our faces pressed to the glass of the sweet shop, we marvel at American abundance, confidence and cultural output. The educated classes maintain the fond illusion that the US is a country of grave statesmen and glamorous Hollywood actors, the America of the West Wing. Yet this same country, from the British perspective, cyclically goes mad.

Good America gives way to Bad America. If Good America is variously quaintly yeehawing and composing New York Times op-eds, Bad America is the dark image of all that is Good and Holy in this our United Kingdom. Ed Davey summoned this familiar but unwelcome spectre on Tuesday:

Just imagine — if you can bear it …

Imagine living in the Trump-inspired country Farage wants us to become. Where there’s no NHS, so patients are hit with crippling insurance bills. Or denied healthcare altogether. That is Trump’s America. Don’t let it become Farage’s Britain.

Where we pay Putin for expensive fossil fuels and destroy our beautiful countryside with fracking — while climate change rages on. That is Trump’s America. Don’t let it become Farage’s Britain.

Where gun laws are rolled back, so schools have to teach our children what to do in case of a mass shooting. Trump’s America. Don’t let it become Farage’s Britain.

Where social media barons are free to poison young minds with impunity. Trump’s America. Don’t let it become Farage’s Britain.

Where the government tramples on our basic rights and freedoms, unconstrained by the European Convention on Human Rights. Where Andrew Tate — Andrew Tate — is held up as an example to young men. Where racism and misogyny get the tacit support of people in power. Where everything is in a constant state of chaos.

That is Trump’s America. Don’t let it become Farage’s Britain.

One might ask any number of searching questions about this diatribe, such as where in the Reform manifesto NHS abolition and the right to bear arms appear. You might also wonder how we are to avoid paying Mr Putin for “expensive fossil fuels” if we’re also opposed to “destroying our beautiful countryside with fracking”. But truth and logical coherence are not the point of the Lib Dems, and they are not the point of Bad America. At the level of poetic and metaphysical truth, Bad America is about both selling out to Putin and drilling for oil in the back garden, it’s about rolling back the state and putting jack boots on the street, it’s about cracking down on people’s freedom by refusing to regulate the internet.

So why is it America that is always the bogeyman? Although geopolitical rivals like Russia, China and Iran may threaten national security, there is something that marks America out as uniquely unsettling. The reason is simple: for all of America’s gleaming modernity, it represents the dead hand of a forgotten history.

America was founded in the 18th century, and that constitutional settlement, along with many elements of English early modern culture, vigorously persists. By contrast, despite the medieval origins of the English state, the British constitution was formalised in the 19th century, and took on its modern form in the early 20th century. Those same norms were even more recently reinvented in the “new normal” of the Blairite settlement, which embedded equalities laws and human rights into the day to day life of law, regulation and public life.

What disturbs so many Brits is that the divide no longer falls cleanly in the Atlantic, but through the heart of ordinary people

These developments are not only a constitutional reality, but reflect fundamental changes in culture, religiosity and worldview that now divide Britain and the USA more surely than the Atlantic. Those elements of American culture that figures like Ed Davey find most alienating are really old features of English culture that we have abandoned along the way.

The libertarian attitude to gun and property rights that now shock English sensibilities were once near universal assumptions. The Metropolitan police was almost not introduced at all because much of the population opposed their introduction. Under common law, ordinary citizens had the power to arrest criminals in the act of a crime, and to use force to do so. Justice, in the form of civilian arrest and jury trials, was a matter shared evenly between crown and people, without recourse to an administrative state. This is why the British police were unarmed, not because there is some unique English horror of weapons, but because it is assumed that ordinary citizens will be armed, should they need to defend themselves, and many citizens formed organised militias. The same motives that saw British police disarmed was behind America’s famous second amendment.

In the same way, the vigour of American religiosity and public rhetoric reflects the enthusiasms of early modern England. This was the age of satirists and pamphlets, where rumour and slanders ran wild and politics often descended into brawls on the street. It was also the time of radical preachers, proliferating sects, and perpetual religious conflict and tension. This higher pitch of emotion in public life, tinged with an extremely open and rhetorically exuberant Christian religiosity simply continued to rage in America. Both populist politics and enthusiastic religion are essentially English traditions which we have gradually left behind.

How did this divergence come about? Britain was tamed by Victorian moralism and the welfare state. Mass democracy was carefully managed by a continuing aristocratic class, and religious conflicts were gradually set aside as Britain attained global power and prosperity. In this new democratic British constitution, conflict was mediated by both public civility, and a newly powerful state machine staffed by a growing civil service. Religious nonconformity and evangelicalism were channeled into commercial and charitable enterprises that often acted in concert with the state. The Quaker Rowntree family gave Britain a confectionary giant, a still massively influential charitable foundation closely tied to government, and the decisively important Rowntree Report, which helped bring about the foundations of the welfare state under the 1906 Liberal government.

Protestant nationalism, which had been the convening principle of 18th century British nationhood, gave way to a kind of philanthropic nationalism, a kind of national Methodism, in which everything from imperial ventures to industrial relations to urban planning was animated by a moderate, rationalist do-goodery. These principles, originally Christian, were also rapidly secularising under the influence of socialists, feminists and free-thinkers.

The powerful concept of English liberty, still potent as late as the 60s and 70s, was finally eroded by the alliance of this philanthropic nationalism with the massive state machine built during the war. The philanthropic principle, once allied to notions of human sympathy and individual charity, was now to be entirely realised through collective redistribution institutions. Rather than charitable gifts and mutual aid, welfare gradually came to be treated as a right and an obligation of an impersonal state. The attitude of the citizen was not to stand up for a pre-existing freedom, but rather to demand rights from the state, and to express “empathy” for those in distress, and support the expansion of rights to such groups. The management of public and private resources was now a matter for utilitarian calculation, not contending duties and virtues.

Meanwhile in America, the strong religious and political inheritances of the 18th century, sufficient to inspire the admiring hopes of European writers like Alexis de Tocqueville, were to continue, but in a sometimes distorted form. Just as England has taken moderation to the point of vice, so America has exaggerated enthusiasm to a dangerous extreme. Just as in England, despite the apparent pervasiveness of religiosity, a quiet secularism has taken hold. The overemphasis on individual liberty has seen Americans lose sight of the common good, and seen consumerism and materialism dominate popular culture. Coarseness, crassness and every kind of crudity are the primary exports of American culture, and it is a commonplace assumption that “do what thou wilt” is the essential basis of individual dignity.

Each country has become a distorted mirror of the other, with Americans sneering at “oi you got a loicense for that?” culture, and Brits mocking the parodic “orange man” who now represents the US on the world stage. Distorted and corrupted, once clearly recognisable shared inheritances, from the common law to the King James Bible, now serve to divide rather than unite the English-speaking world.

What disturbs so many Brits is that this divide no longer falls cleanly in the Atlantic, but increasingly runs through the heart of ordinary people. Social media, along with an already pervasive mass culture, has imposed an unexpected intimacy between the estranged countries. The JS Mill England of vegetarianism and open borders finds easy solidarity with snooty New England elites in their mutual disdain for the uncouth redneck. American liberals solemnly, if insincerely, invoke the NHS and European Social Democracy. British progressives worship at the altar of American radical chic.

The assumption that this feeling of solidarity was shared by other Britons is now being unsettled. Nigel Farage openly courts Trump, and the “Bad America” he represents. Many Brits, angered by lockdown and mass migration, have turned on the state itself, and the “omniparty” of the British establishment. Libertarian ideas start to make sense in the context of a wallowing, predatorily redistributive state, and old ideas of Christian nationalism are given new force in the context of a rising Islam and an ambiguous national identity. And all of these ideas are presented with a new rhetorical intensity, encouraged by the algorithmic anarchy of social media.

It takes a leap of the imagination and an act of intellectual humility to realise that a culture that you look down upon has ideas, however corrupted, that you yourself might need. The very notions whose absurdity bolstered your sense of self-confidence, might be the ones you now need to embrace. Britain needs American enthusiasm, frankness, religiosity, sincerity, and love of liberty. We have lost some essential sense of dignity in relation to the state, allowing our political and moral duties to be outsourced, never worrying about the price. But in equal measure, America is a country that has forgotten the common good, and could learn much from British moderation, humour, common sense, cooperation, stoicism and unselfishness. Could America and Britain inspire one another in virtue? Or are we doomed to drag ourselves down to perdition, clawing at each other all the way?