A critical ocean current that keeps parts of the world from freezing over is at risk of completely shutting down within decades.

A research team from Europe found that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) could collapse after 2100, especially if greenhouse gas emissions remain high.

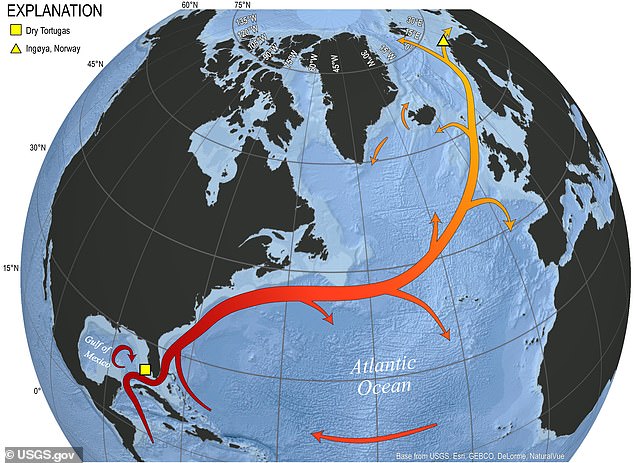

The AMOC is like a giant ocean conveyor belt that moves warm water from the tropics to the northern Atlantic, with the Gulf Stream playing a key role, acting as the main current carrying that warm water along the US East Coast to the north.

It helps keep places like northwestern Europe and the northeastern US milder in winter and influences weather patterns worldwide, including tropical rainfall.

However, if the AMOC shuts down, it could cause colder winters and drier summers in the Northeast, raise sea levels along the East Coast, and disrupt fishing industries for American businesses.

Scientists have warned that the collapse could be triggered by global warming, which stops deep ocean waters from mixing in northern seas like the Labrador and Nordic Seas by making surface water warmer and less salty.

This creates a cycle where the AMOC weakens, bringing less warm, salty water north, which further prevents water from sinking and slows the current down to its breaking point.

The new study found that cutting emissions quickly is crucial to reduce this risk, but some scenarios predicted that it may already be too late to completely prevent a collapse in the near future.

Movies like The Day After Tomorrow envisioned a similar scenario, where climate change fuels a massive winter in New York

The Gulf Steam: This warm, swift current starts in the Gulf of Mexico, flows through the straits of Florida and toward North Carolina, then turns eastward as it moves toward northwestern Europe

Researchers from the Netherlands, Germany, and the UK used computer models from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) to make their dire predictions.

These models are used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to predict future climate changes.

The team focused on simulations extending beyond 2100, up to the years 2300 and 2500, to see the long-term fate of the AMOC under various levels of global warming.

In all nine of their models simulating high greenhouse gas emissions worldwide, the AMOC shut down completely by the year 2100.

In the US, the Atlantic current brings warm water to New England, New York, and the Atlantic coast.

A shutdown could lead to bitter winters, with less heat reaching the region annually. Cities like Boston or New York City might experience harsher weather, increasing heating costs and straining energy systems.

A collapse of the current could also alter hurricane paths or intensity, potentially increasing storm risks in places like Florida, the Carolinas, or the Gulf Coast.

Sea levels may rise faster from North Carolina to Maine. Since the AMOC normally pushes water away from the coast, its weakening would cause water to build up, worsening flooding risks in coastal areas like Florida, Virginia, and Massachusetts.

A shutdown could lead to bitter winters, with less heat reaching the region annually. Cities like Boston or New York City might experience harsher weather, increasing heating costs and straining energy systems

Stefan Rahmstorf from the University of Potsdam said: ‘In the simulations, the tipping point in key North Atlantic seas typically occurs in the next few decades, which is very concerning.’

Sybren Drijfhout from the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute added: ‘The deep overturning in the northern Atlantic slows drastically by 2100 and completely shuts off thereafter in all high-emission scenarios, and even in some intermediate and low-emission scenarios.’

‘That shows the shutdown risk is more serious than many people realize,’ Drijfhout, the study’s lead author, warned in a statement.

The study, published in Environmental Research Letters, found that the collapse will start with a failure of heavy, cold, and salty surface water to sink and blend with deeper ocean water that keeps the AMOC flowing in the North Atlantic Ocean around 2050.

This would then lead to a weaker AMOC, which completely shuts down over the following 50 to 100 years.

A shutdown of the Atlantic current would drastically reduce the heat being transported north by roughly 20 to 40 percent.

In some of the team’s simulations, heat released into the atmosphere in places like Canada, Scandinavia, and the northern US would drop to nearly zero, causing a strong chilling effect in these areas.

Study authors warned that the world is already showing signs that the collapse is coming.

Recent data showed a slight decline in deep ocean mixing over the past decade in the northern seas, which matched up with the study’s findings.

However, the team warned that more recent factors, like melting glaciers, weren’t taken into account, so the collapse could come even sooner than experts think.

‘These standard models do not include the extra fresh water from ice loss in Greenland, which would likely push the system even further. This is why it is crucial to cut emissions fast,’ Rahmstorf said.