A JAB dished out for free on the NHS “dramatically reduces” the risk of pregnancy complications as well as cancer, a new study suggests.

Women who received the HPV vaccine at school were less likely to suffer pre-eclampsia, bleeding or have their waters break early, University of Aberdeen researchers said.

HPV, or human papillomavirus, is a common group of viruses that affect the skin and usually cause no symptoms.

They’re spread through close skin-to-skin contact, such as during sex.

Most types are harmless but some high-risk strains can cause genital warts or abnormal cell changes that can turn into cancer.

A jab that reduces the risk of HPV is offered to children aged 12 to 13, though people can get catchup vaccines up to the age of 24.

Now, Scottish researchers say the jab’s benefits can extend beyond cancer prevention.

The study, published in the European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology and Reproductive Biology, is the first to investigate the link between HPV vaccination and a broad range of pregnancy complications, authors said.

Researchers examined data collected from some 9,200 women in Aberdeen who were pregnant between 2006 and 2020.

They were all aged between 20 and 30 at the time of giving birth – some were vaccinated against HPV and some weren’t.

In Scotland – and the rest of the UK – school programmes vaccinating girls against HPV and catchup programmes started in 2008.

The vaccine also started being offered to boys in 2019.

Researchers examined how HPV vaccination was linked to a number of pregnancy outcomes, including premature birth between 20 and 37 weeks, low birth weight and preterm prelabour rupture of membranes – when when the waters break before labour begins and before 37 weeks.

They also looked at prelabour rupture of membranes – when waters break before labour – chorioamnionitis, the threat of miscarriage, pre-eclampsia, and antepartum haemorrhage, bleeding after 24 weeks of pregnancy.

HPV jabs didn’t seem to affect the risk of premature birth.

But the results showed a clear reduction in pre-eclampsia, pre-term prelabour rupture of membranes and antepartum haemorrhage in women who had been vaccinated against HPV.

Dr Andrea Woolner, a senior clinical lecturer at the University of Aberdeen and honorary consultant obstetrician and early pregnancy lead at NHS Grampian, who led the research, said: “We found that women vaccinated against HPV had better outcomes than those who were not vaccinated for several common pregnancy complications.

“This reinforces the importance of uptake of the HPV vaccine before the age of 15 years.

“Not only does the HPV vaccine protect against cancer – we have found in our research, that the vaccine may also protect against serious pregnancy related complications.”

It’s generally encouraged that people get their HPV vaccine before becoming sexually active, in order to get the best protection.

Everything you need to know about the HPV vaccine

The HPV vaccine protects against some of the risky HPV types that can lead to genital warts and cancer.

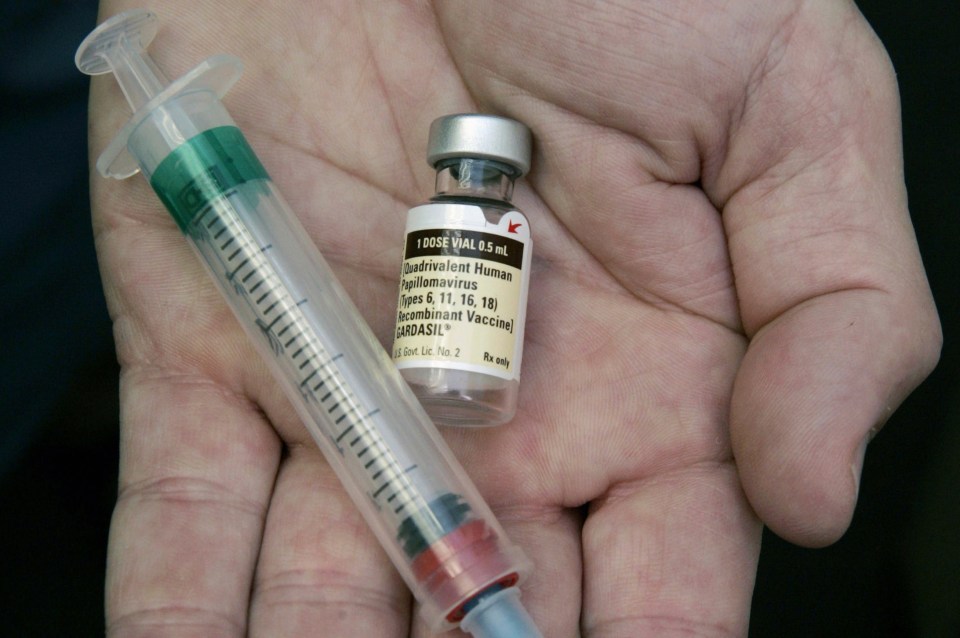

Gardasil has been the HPV vaccine used in the NHS vaccination programme since 2012. It is protective against nine types of HPV.

For example it is effective against types 16 and 18 which cause around 80 per cent of cervical cancers in the UK.

That’s why it is important for people who have a cervix to still get a smear test when invited by the NHS.

Cervical cancer takes the lives of about 850 people a year currently – but this is expected to continue decreasing thanks to the vaccine.

There are around 3,300 new cases of the devastating cancer a year, with peak incidence in women in their early 30s.

But the HPV vaccine doesn’t just prevent cervical cancer – it stops some anal, genital (vaginal and penile), mouth and throat (head and neck) cancers.

These affect both men and women.

Who should take it?

The first dose of the HPV vaccine is routinely offered to girls and boys aged 12 and 13 in school Year 8.

The second dose is offered 6 to 24 months after the 1st dose.

If a school child misses their doses, you can speak to the school jab team or GP surgery to book as soon as possible.

Anyone who missed their jab can get it up to their 25th birthday.

But people who have the first dose of the HPV vaccine at 15 years of age or above will need to have three doses of the vaccine because they do not respond as well to two doses as younger people do.

The HPV vaccine used to only be given to girls who are at risk of cervical cancer when they are older.

But in 2018, it was announced that boys – who can get HPV-related cancers of the head, nech, anal and genitals – would also be given a jab.

Girls indirectly protect boys against HPV related cancers and genital warts because girls will not pass HPV on to them.

But the programme was extended to further eliminate risk of the virus spreading in the future.

Men who have sex with men (gay and bisexual) do not benefit from this indirect protection, and so are also able to get the HPV vaccine up to the age of 45.

Some transgender people can also get the vaccine.

Those assigned female at birth would have gotten one as a child. But those assigned male at birth could get a jab if they transition to female and have sex with men.

Dr Xiaoqian Xu, who collaborated on the study added: “Our results highlight the benefits of HPV vaccination, and fundamentally, the benefits of the vaccination early.

“The HPV vaccine is most effective if administered before any sexual activity so early HPV vaccination is vital, delaying or catching up later may miss the best chance to protect both against cancer and pregnancy complications”.

It’s not uncommon to get an HPV infection during pregnancy, as it’s a common STI that 85 per cent of people will get at some point in their lives, according to Patient.info.

In most cases it’s harmless, but research suggests HPV can increase the chance of premature birth, miscarriage, high blood pressure during pregnancy, growth problems, and low birth weight.

Dr Woolner explained: “We know from previous research that if the pregnant mother had previously had HPV infection, or previously undergone treatment to the cervix for precancerous changes, they were at an increased risk of pregnancy complications such as preterm birth.

“So, we wanted to know if having the HPV vaccine, reducing the likelihood of HPV infection and thereby the need for cervical treatments would reduce the chances of some of these pregnancy complications.”

Study authors said future research should look at whether HPV jabs can benefit male fertility.

Dr Maggie Cruickshank, emeritus professor at the University of Aberdeen and consultant gynaecologist at NHS Grampian, added: “Vaccinating boys alongside girls enhances herd immunity, significantly reducing the risk of HPV-related cancers in all genders and supporting healthier pregnancies in the future.

“These new findings also open the door to exploring additional benefits of the HPV vaccine for men.”

It comes after health bosses sounded the alarm over low uptake of HPV jabs in certain parts of England leaving young women vulnerable to cervical cancer and other forms of the disease caused by the viruses.

High-risk strains can increase people’s chances of developing cervical cancer, as well as mouth, anal, penile, vulval and vaginal cancer.

Health bosses have made it their mission to eliminate cervical cancer in England by 2040.