A fragile French Cabinet was readying itself at the weekend for an early battle over Prime Minister Sébastien Lecornu’s belt-tightening budget, as opposition parties sought new opportunities to bring the government down.

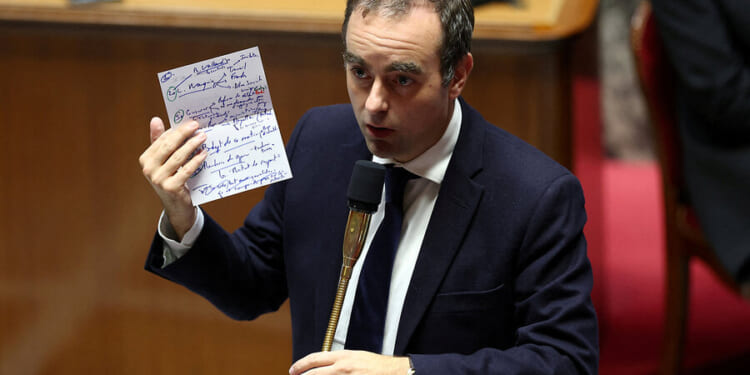

Steering French politics into slightly calmer waters, Mr. Lecornu narrowly survived two no-confidence votes in Parliament on Thursday, winning a reprieve for his days-old government but paving the way for a tough budget debate.

Mr. Lecornu is the seventh prime minister to hold that post since President Emmanuel Macron took office in 2017, a sign of political instability that most French citizens blame on their politicians – especially on Mr. Macron.

Why We Wrote This

France has become a byword for political instability – nine governments in eight years – and French voters are increasingly fed up with their politicians. But beyond the uncertainty, they still have faith in their institutions.

“French people aren’t fed up with politics, we’re fed up with politicians,” says Charles Bok, standing at the long metal counter of a popular Parisian café, reading a newspaper. “It’s always the same characters, over and over. We’re in a vicious cycle.”

Questions continue to swirl over both Mr. Macron’s ability to lead the country and why opposition parties have been unable to find compromises and work together. Some of Mr. Macron’s closest allies have said he should step down, while his critics have gone as far as to call France ungovernable.

Even amid the country’s ongoing political crisis, and despite growing disenchantment with their politicians, a majority of French people say they still have faith in their institutions. But they are demanding change. And many say that only a major shake-up can heal France’s political fractures.

“I don’t like the word ‘crisis,’ but this is definitely an unprecedented situation in the history of the Fifth Republic,” founded in 1958, says Pierre Bréchon, professor emeritus of political science at Sciences Po Grenoble. “Political parties are too radical, no one is willing to make concessions. Things have reached vaudeville proportions.”

Faith in politicians erodes

But everything is relative, says Miroslav Antonic. He moved to France 20 years ago from Serbia, after a decade of war in the former Yugoslavia.

“When you compare France with other countries outside Western Europe, it’s doing pretty well,” says Mr. Antonic, leaning against the same metal café counter as Mr. Bok. “My country is very corrupt, autocratic. France is at least an organized country.”

Still, though Mr. Antonic says he continues to vote and read the news, he has found it harder to have faith in French politicians or to expect change when the same faces reappear at each election.

Dominique de Villepin and Edouard Philippe, both former prime ministers, have hinted at their intentions to run for president in 2027. When Mr. Lecornu formed his first Cabinet last month, he retained two-thirds of the ministers from the previous government.

Meanwhile, the recent criminal convictions of far-right leader Marine Le Pen and former President Nicolas Sarkozy have only confirmed a sense among the French that their politicians are corrupt. Ms. Le Pen was found guilty of embezzling European Parliament funds, while Mr. Sarkozy, who will go to prison next week, was convicted of criminal conspiracy in connection with alleged Libyan funding of his 2007 election campaign.

Few voters believe Ms. Le Pen’s and Mr. Sarkozy’s protestations that they have been victimized by the judicial system.

In an annual poll by the Center For Political Research at Sciences Po, only 26% of French people said they trusted politicians, using words like “wariness,” “illegitimate,” and “corrupt” in connection with their leaders. Germans and Italians, by contrast, approved of their politicians at a rate of 47% and 39%, respectively.

“People are tired and they reject the entire political class,” says Martin Quencez, a political analyst in Paris for the German Marshall Fund of the United States. “That used to be a sentiment that would help the center or right, but now it covers all parties. There is this feeling that we need a major change.”

When “compromise” equates to “giving in”

That change could come in several forms. Mr. Philippe, Mr. Macron’s first prime minister, suggested this month that the president should cut his losses and step down. More than budget negotiations or differences on any single issue, the French still haven’t forgiven Mr. Macron for calling snap elections in July 2024 that resulted in the current political deadlock.

After his party’s defeat in the European elections in late June last year, Mr. Macron dissolved Parliament and called new elections. But instead of bringing more clarity, the vote resulted in a hung Parliament, in which none of three mutually hostile blocs command a majority.

Mr. Macron could have picked a new prime minister from the left-wing alliance, which had edged ahead of the far-right and center parties. But he chose a right-wing ally, angering a wide range of voters, including supporters of his originally more centrist policies.

Dr. Bréchon, the political science professor, says the dissolution was the moment when France experienced a seismic shift, showing that neither the government nor the opposition were willing to follow the examples of Germany’s or Spain’s coalition governments. In France, “compromise” is equated with “giving in.”

Mr. Macron could still walk away, say observers, but he is more likely to hang on until the next presidential election in 2027.

“Is this all Macron’s fault? No,” says Benjamin Morel, a public law professor at the Université Paris 2 Panthéon-Assas. “But he has definitely become an irritant to a large part of his own party.”

Those not calling for Mr. Macron’s resignation say other things need to happen to change the political landscape. Young people need to stay engaged in politics. Opposition parties should start working together like their European neighbors. The public should still get out and vote.

But some people, including Coline Verger, want a drastic change. She says she finds the current situation “comical” and yet can’t help reading the news each morning.

“Honestly, I’d like it very much if there was another movement like the Yellow Vest movement,” says Ms. Verger, referring to the year-long protests that began in 2018 against rising fuel prices and the high cost of living. “I think instead of a small protest each week, we need one huge one that blocks everything. That’s how the French Revolution took place.

“We need to stop complaining, have a true rupture with what’s happening and revive our country. I’m not giving up yet.”