Forty years ago, Margaret Thatcher’s government signed the Anglo-Irish Agreement, which for the first time gave the Republic of Ireland a say in governing Northern Ireland. While the province remembered this turbulent time, MPs voted on Tuesday for Labour’s Troubles legacy bill, during its second reading in the House of Commons. This legislation is based on a “joint framework” on the past, agreed in September between British and Irish ministers, who met again this week to discuss its implementation at an Intergovernmental Conference.

The timing was either unfortunate, or as Ulster’s only unionist daily newspaper, the Belfast News Letter, suggested in an editorial, a “truly sickening” display of insensitivity.

Ulster unionists remember the 1985 agreement as a devastating act of betrayal by their government, perhaps rivalled in the intervening 40 years only by the Northern Ireland Protocol. They believe it should have acted as a warning for subsequent British governments never to trust Dublin. Instead, Keir Starmer and Hilary Benn, the Northern Ireland secretary, recently capitulated again to nationalists’ demands on dealing with Troubles-era crimes.

They replaced the Tories’ Legacy Act and restarted the unbalanced system of inquests and civil cases against members of the armed forces. This process was co-designed with Dublin, but included few meaningful commitments from the Republic. The Irish government has so far refused even to drop an interstate case against Britain on legacy at the European Court of Human Rights. It claims that it will wait to see how the UK implements the framework. The implication is that, while nothing is guaranteed from Dublin, it will make sure Britain behaves.

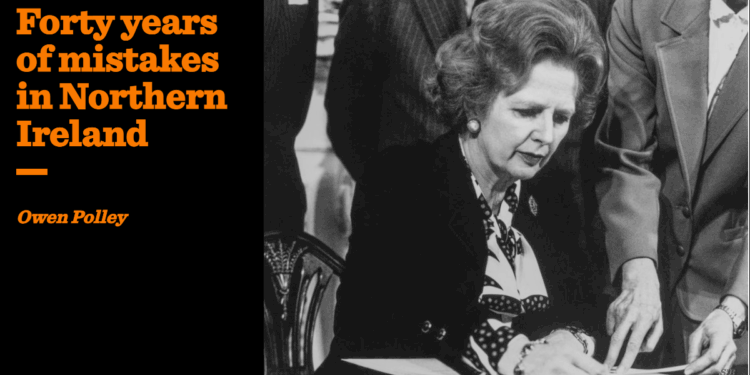

The echoes of the disastrous AIA are striking. After Margaret Thatcher’s government negotiated that deal in November 1985, she regretted it almost immediately. In fact, according to some of her closest confidantes, she became more troubled by this misjudgement towards the end of her life. For that reason, her aide at the time, Charles Powell (now Lord Powell), told the News Letter this week that he believed the former prime minister died with, “Northern Ireland lying on her heart”. The phrase was a reference to the words of Mary Tudor, who was so devastated by the loss of Calais to the French in 1558 that she said, if her body was cut open, Calais would be found “lying on her heart.”

The AIA gave the Irish government a consultative role in Northern Ireland and Mrs Thatcher was adamant it would not affect the province’s constitutional status. In return, though, the government thought it had secured more cooperation from the Republic on combatting IRA terrorism. It also expected John Hume’s nationalist SDLP to take a more constructive approach to the security forces in Northern Ireland. Neither of these objectives were delivered. The Republic’s judicial system continued to block extradition requests for wanted terrorists and its politicians refused to deploy adequate resources to tackle paramilitary activity on its border. As a result, IRA violence escalated rather than tapering off, while Hume continued to posture against the state, refusing to make simple gestures of reconciliation like attending the funerals of Catholic RUC officers.

The longer-term legacy of the AIA has been baleful too. The Dublin government has pushed the boundaries of its initially limited role in Northern Ireland remorselessly, with little resistance from Westminster. The Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement of 1998 was supposed to curtail this interference, by setting down strict parameters for all-island cooperation and preventing the Republic meddling in the province’s internal affairs. David Trimble justified this controversial deal, which dismantled the Royal Ulster Constabulary and freed paramilitary prisoners, as well as giving terrorists a place in devolved government, by arguing that it removed the hated Anglo-Irish accord. For its part, the Irish government simply ignored the document’s text, claiming instead that the mysterious “spirit” of the Good Friday Agreement justified every intrusion into Northern Ireland’s business.

When the AIA was signed in 1985, unionists, who had been frozen out of the negotiations, reacted with astonishment and fury

The Irish Sea border, which met Dublin’s demands and ignored unionists’ rights as British citizens, was squarely in the tradition of the AIA. The Windsor Framework not only cut Northern Ireland off from the mainstream UK economy, it restricted the ability of Westminster and Stormont to legislate for the province, so that its laws would remain in line with those of the Republic.

When the AIA was signed in 1985, unionists, who had been frozen out of the negotiations, reacted with astonishment and fury. Unionist MPs resigned from the House of Commons en masse, there were campaigns of civil disobedience and 100,000 people rallied against the agreement at Belfast City Hall. Many critics claimed this response was out of proportion and the Republic’s limited say in Northern Ireland was harmless, but those arguments look even more ridiculous given what has happened since.

The latest affront, the legacy bill, effectively gives Dublin a veto over Britain’s policies on dealing with the Troubles, while requiring no examination of the Republic’s role in sheltering and arming IRA terrorists. The Irish government is proceeding with its interstate case to ensure Westminster meets all its demands, but it has not brought forward any legislation to meet the limited undertakings it made in the framework. In the House of Lords, Baroness Hoey argued recently that, considering this latent hostility, “It is time we stop treating the Irish government as a close friend.” Mrs Thatcher learned that lesson quickly, it’s a travesty that British governments are still repeating her mistake forty years later.