The city of Roseville, 19 miles northeast of Sacramento, regularly sits at the top of California’s “best places to live” lists. The traffic is reasonable, the weather sunny, and the homes comparatively affordable. There are bike paths and well-ranked schools and, on one recent morning, even an outdoor step aerobics class cheerfully underway in a downtown park.

But there is another reason this railroad town now with some 160,000 residents gets such high accolades. After two decades of careful municipal planning, it has no problem with flooding.

To outsiders, this might seem like a strange claim to fame for a city in California’s Central Valley, away from the coasts and rising sea levels. But as people here know, the Sacramento Valley sits in a highly vulnerable flood plain. During the 1980s and ’90s, this city made national news when its creeks overflowed due to heavy rain. Hundreds of homes were destroyed. President Bill Clinton came to console. And Roseville began a full-scale reimagining of how to protect itself from water.

Why We Wrote This

Recent disasters in Texas and North Carolina underscore how costly interior floods can be. After Roseville, California, was hit by destructive floods in the 1980s and ’90s, the city turned itself into a model of preparedness and hazard mitigation.

Now, a quarter century later, the city is regularly held up as a model as other municipalities across the United States increasingly focus on the risk of inland flooding. This summer’s flash flooding in Texas Hill Country was a stark reminder that floods away from the coasts are one of the deadliest, and most financially costly, severe weather events in the U.S.

“Roseville is one of those communities that is ahead of the curve,” says David Feldman, professor emeritus with the department of urban planning and public policy at the University of California, Irvine. “They definitely get it.”

Its approach is not flashy. Talk to Brian Walker, Roseville’s senior engineer and flood plain manager, and you’ll hear a lot about flood plain mapping and storm drainage, funding mechanisms and development ordinances. But this measured and deliberate approach has worked, he and others say.

Roseville was the first city in the U.S. to receive the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) top rating for flood preparedness; residents still receive discounts on home insurance policies because of it. Mr. Walker also works closely with businesses in town. New residential neighborhoods are booming across the city, and last year Bosch announced a $1.9 billion upgrade to its Roseville site, where it plans to produce and test semiconductors.

“Hazard mitigation has real-world implications for families and for businesses,” Mr. Walker says. “If we’re prepared, people can maybe hose out their garage that got a little bit wet and then get back to business.”

Growing awareness in local communities

Earlier this year, the National Weather Service predicted that 2025 would well surpass the annual average of 4,000 flash flood warnings. The reasons for this vary from location to location, but often include a growing number of extreme rain events, as well as infrastructure challenges. More inland flooding means an increased likelihood of tragedies, such as in Texas earlier this year and the destruction from Hurricane Helene in the mountains of North Carolina last year. Monetary strain on cities and towns from New Mexico to New Jersey, from Kentucky to Vermont, is also growing.

“Local communities are becoming more aware of [floods] for a number of reasons,” Dr. Feldman says. “The cost of flooding, and the ultimate costs on residents and local governments, is increasing.”

Some of these costs are direct, such as for emergency response during a crisis. But there is also infrastructure repair, lost tax revenue, and the expense of future mitigation projects.

And there is always the issue of insurance.

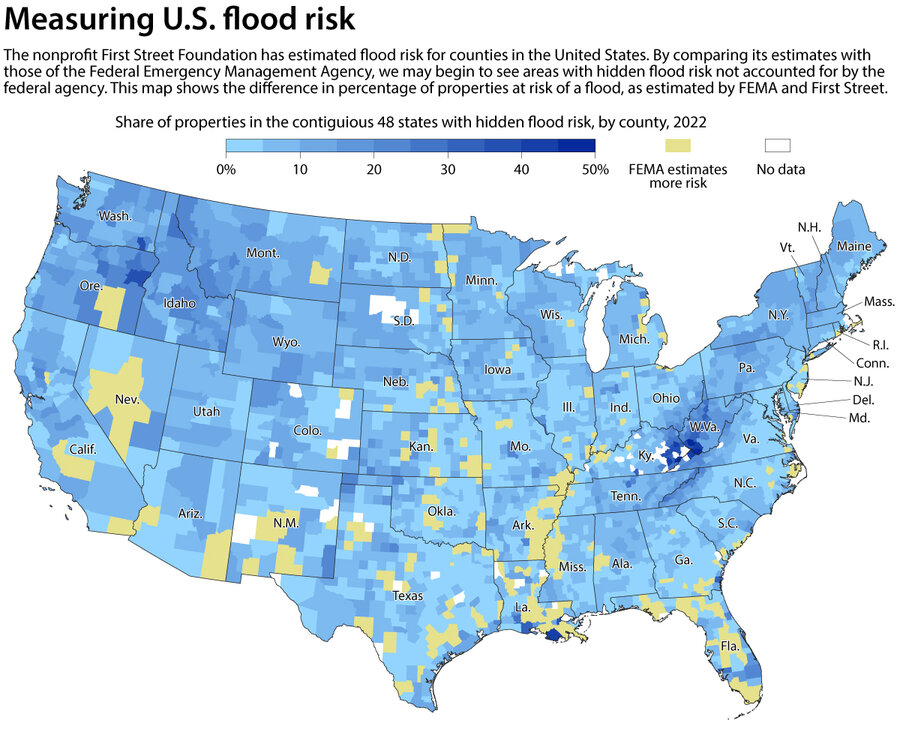

Homeowners who live in high-risk flood areas must have flood insurance to get a mortgage. But those policies are expensive. Many researchers also point out that FEMA maps do not consider future development or climate change, so they tend to underestimate flood risk.

“FEMA’s flood maps are based on a historical average, but we know that with climate change, the past isn’t going to be like the future in terms of the type of flooding that we see and the extent of flooding that we see,” says Joel Scata, senior attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council.

This is why Roseville has long viewed federal flood maps as a minimum standard, says Mr. Walker.

“I think that FEMA’s maps are a huge asset for the country,” he says, adding that he and others in Placer County work regularly with FEMA to update maps and use them as a baseline. “FEMA doesn’t want to require communities to do what Roseville does. Roseville elected to say, ‘FEMA maps are great, but we want to do better.’”

Roseville analyzes flood risk by looking ahead to future development plans, both residential and commercial, in addition to assessing current development, he says. Then, officials take the maximum possible build-out of all those areas and analyze the flood risk, stormwater runoff, and other hazards based on that. With that information, the city creates its own maps and hazard ratings for citizens to access.

Those areas alongside Roseville’s 78 miles of creeks, for instance, tend to be open space, which can help manage the fierce bouts of rain that happen when an atmospheric river drops a fire hose of water on this city.

That means more restrictions on development, Mr. Walker acknowledges. But it also means space for a vast network of bike trails and parks that have become one of the big draws of the city. Additionally, it has prevented the situation facing Florida and other states where pricey businesses and homes are built in those places most likely to flood.

“If there’s one thing that I would say that is the most beneficial for mitigating flood risk, I’d say it is Roseville’s choice to define our flood plains more conservatively,” Mr. Walker says. “So, we define the risk, and then we keep structures and development outside of those risky areas.”

From containing water, to working with it

Across the street from Roseville’s city government offices, over a pedestrian bridge covering both a bike path and a creek, Mr. Walker points out the high-water marker from the city’s 1995 flood. It’s almost as tall as he is.

This park was under several feet of water, he says – and planners here do not forget it. When they renovated the pedestrian bridges, they made sure to make them extra high so that even a flooded creek would rush under them.

“We were very mindful about not inducing any flood risk to the area,” he says. “In all of our projects, we strive for having zero flood impact.”

This, says Dr. Feldman, is what cities will increasingly need to do. Historically, municipalities created infrastructure to try to contain water. (And after its flooding, Roseville, too, built levees.) Now, they must try to work with it.

“There’s a growing awareness of the fact that so-called structural measures to alleviate floods, that is to say, building of dams, levees, fortifications of various types, are not a panacea,” he says. “You have to be more imaginative.”

Individuals and businesses also need to take more responsibility, Dr. Feldman argues. If developers build in an area at risk of flooding, they should have to bear a greater share of the wider costs of flood mitigation and repair. The city of Sacramento, for instance, has created a flood insurance model that essentially does this, he says.

“I think what we’re beginning to learn … is that you do have to take action locally,” he says. “You cannot depend on the cavalry coming to the rescue after a flood disaster. You cannot depend solely upon the government, and you certainly can’t depend solely on flood insurance or even FEMA flood insurance. The risks are too great.”