Finland has belatedly admitted its air force flags probably should not have a huge swastika in the middle.

The Nordic country is set to remove the symbol from the standard because its presence has created ‘awkward situations with foreign visitors’.

The nation adopted the insignia as the emblem of its airborne military when it was founded in 1918.

This was years before Germany‘s Nazi Party chose the swastika as its crest and became primarily associated with the logo during its rise to power in the 1930s.

Finnish air force commanders removed the symbol from widespread usage in 2020 – but five years on, it remained on the flags of some units, the Telegraph reports.

Now, the swastika – which is illegal in many European nations, including Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic – will be banned across the entire fleet.

Colonel Tomi Böhm told Finland’s public broadcaster YLE: ‘We could have continued with this flag but sometimes awkward situations can arise with foreign visitors.

‘It is wise to live with the times.’

Finland has belatedly admitted its air force flags (pictured last year) probably should not have a huge swastika in the middle

The Nordic country is set to remove the symbol from the standard (pictured in 2019) because its presence has created ‘awkward situations with foreign visitors’

The nation adopted the insignia as the emblem of its airborne military when it was founded in 1918. Pictured: An air force flag in 2019

The new chief of peacetime unit Karelia Air Wing continued: ‘The world has changed and we live according to the times. There has been no political pressure to do this.’

The commander added he hoped the change would happen during his time in post.

Flags will from now on bear a new emblem of a golden eagle in flight, over a blue circle, surrounded by white wings.

Plans to redo the unit flags were proposed in 2023, the year Finland joined Nato – but some kept using the swastika, raising eyebrows in the international community.

Finland’s government noted it was seen as an ’embarrassing symbol in international contexts’.

It added it wishes to ‘update the symbolism and emblems of the flags to better reflect the current identity of the air force’.

The country has seen public discourse about the use of the swastika on air force flags reawaken in recent times.

It comes after the publication of a book named History Of The Swastika by Dr Teivo Teivainen, a professor at the University of Helsinki.

Flags will from now on bear a new emblem of a golden eagle in flight, over a blue circle, surrounded by white wings (pictured)

He said Finland has always maintained its air force’s use of the symbol has ‘nothing to do with the Nazi swastika’.

This comes despite the country briefly allying with Nazi Germany during the Second World War.

A blue swastika on a white background was emblazoned on all Finnish planes as the national symbol from 1918 to 1945, during its intervention in the major global conflict.

After the war ended, the crest was taken off some flags – but many units, as well as the Air Force Academy, continued to use it on their standards and decorations.

But now Finland has joined Nato, the 32-state defensive alliance established in 1949, the government has changed tack, Dr Teivainen explained.

‘There’s now a need to get more integrated with the forces of countries such as Germany, the Netherlands and France – countries where the swastika is clearly a negative symbol,’ he continued.

He recalled a notable moment in 2021, when German air force units withdrew from a ceremony at a base in Finland’s Lapland region when they learnt swastikas would be displayed.

Before it became synonymous with fascism, the swastika was a widely used and innocuous motif.

A blue swastika on a white background was emblazoned on all Finnish planes as the national symbol from 1918 to 1945. Pictured: Historic Finnish airforce planes featuring the blue swastika

Meaning ‘wellbeing’ in the ancient Indian language of Sanskrit, it was even widely seen as a good luck symbol at the start of the 20th century.

This was how it found its way into the Finnish air force, the New York Times reports.

The country declared independence from Russia in 1918, after the Bolshevik Revolution.

An aircraft, bearing a swastika as a good luck symbol, was gifted to Finnish anti-communist forces in the civil war that ensued.

But, in a subject of controversy, Erik von Rosen, the Swedish aristocrat behind the present, was later close with Nazi figures.

The symbol was also previously widely used in advertising, including by Coca-Cola and on Carlsberg beer bottles, the BBC reports.

The sign was used by American military units during World War One and on RAF planes as late as 1939.

But most of these previously inoffensive uses stopped when the swastika began to be associated with Nazism.

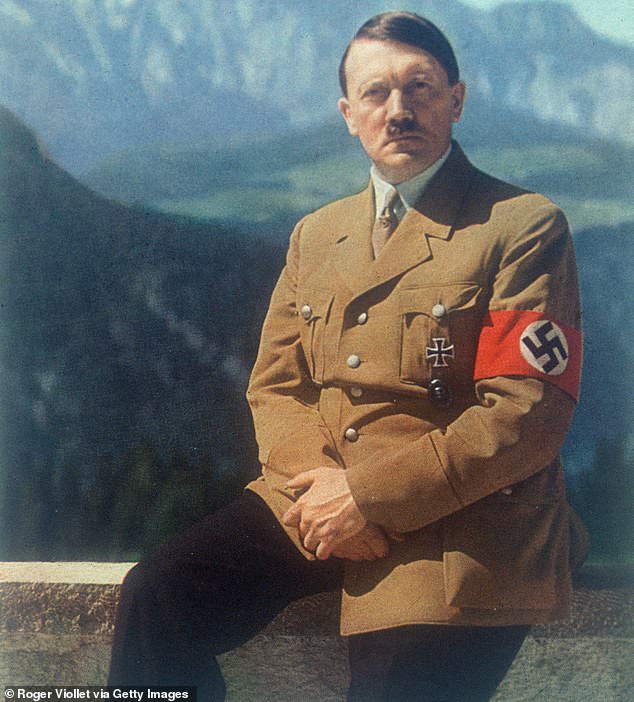

The black swastika of Nazism (pictured, on the armband of far-right Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler, in 1935), on a white circle and red background, has become one of the most despised symbols of the 20th century

The far-right party used it because of the work of 19th-century German scholars on translating ancient Indian texts, who noted similarities between Sanskrit and their language.

The thinkers felt this meant Indians and Germans had a shared ancestry and thought up a race of white godly warriors they dubbed Aryans.

This was taken to extremes by the Nazis who used the swastika as a sign of Aryanism as the ancient heritage of the German nation.

It means the black swastika, on a white circle and red background, has become one of the most despised symbols of the 20th century.

Holocaust survivor Freddie Knoller previously said: ‘For the Jewish people the swastika is a symbol of fear, of suppression, and of extermination.’

Germany banned the swastika at the end of World War Two, before attempting unsuccessfully in 2007 to prohibit it across the EU.

In certain cultures, the swastika is still considered a sacred symbol – which has caused widespread confusion and revision of positions.

Before the Tokyo Olympics in 2021, a Japanese mapmaker said it would stop using the manji – a swastika-type symbol – to mark temples, to avoid any such confusion.