The irony cannot have been lost on Sir Keir Starmer.

Three British tech companies were falling prey to foreign predators on Monday.

That was bad enough in itself for the Prime Minister, but the timing was worse.

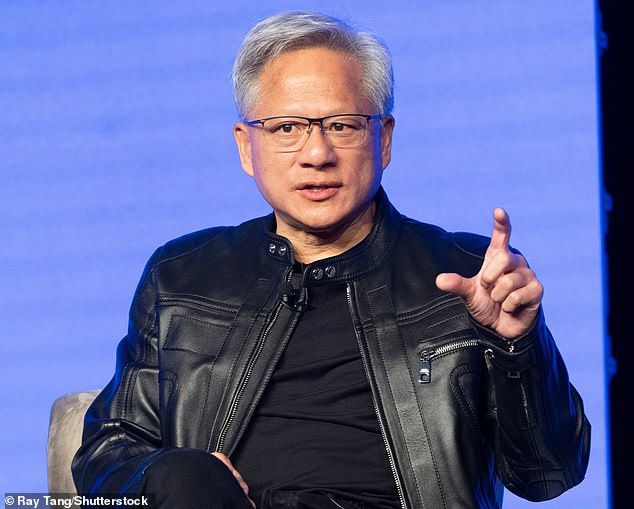

The news came just as Nvidia boss Jensen Huang was warning, in front of Starmer, that the UK does not have the digital infrastructure to realise the potential of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Mr Huang built Nvidia, his Silicon Valley chipmaker, from scratch over three decades. It is now the world’s largest listed company with a £2.6trillion valuation – almost the size of the entire annual output of the UK economy.

The chances of a British technology unicorn growing to anything like that scale are vanishingly small.

That’s certainly the case with the cutting-edge tech firms that were gobbled up on Monday.

So why is there an exodus of our most promising tech companies overseas? Can anything be done to stem the flow? And in the meantime, how can you profit from it?

Two big deals were agreed this week.

Microchip designer Alphawave signed up to a £1.8billion takeover by US software giant Qualcomm.

In a second deal, scientific instruments maker Spectris is recommending a £3.7billion approach from US buy-out firm Advent.

Shares in both companies soared after their bidders offered to pay a substantial premium to take control.

Nvidia boss Jensen Huang with Sir Keir Starmer during London Teck Week

Mr Huang warned that the UK does not have the digital infrastructure to realise the potential of Artificial Intelligence

The third company to fall on Monday was Oxford Ionics, a privately owned quantum computing start-up founded by two Oxford University PhD students. It sold out to a larger US tech firm for over £800million.

For decades Britain has suffered from a chronic funding gap.

New and innovative companies would grow to a certain size only to find themselves starved of the fresh capital needed to take them to the next phase. In effect, that forced them to sell-up.

The problem is that banks were reluctant to provide long-term funding and firms themselves were too small to raise money from outside investors by listing their shares on the stock market.

The problem was so acute that a venture capital firm, which eventually became known as 3i, was formed in 1945 to help rebuild Britain after the after the Second World War.

It was set up by the Bank of England and major British lenders to provide long-term investment funding for small and medium-sized companies – or SMEs.

The Alternative Investment Market, founded thirty years ago, helped to open up stock markets to more domestic companies that wanted to grow.

But SMEs in general, and tech ones in particular, are risky investments.

Their financial backers can make a fortune – or lose all their money.

So big investors, including pension funds, gave such businesses a wide berth.

Just 1 pc of the £4.6trillion of assets owned by UK pensions and insurance companies is invested in private, unlisted UK companies.

As demand from these big investors for stakes in domestic companies fell, so too did their share prices.

That left companies either vulnerable to takeover from larger overseas rivals – or looking to other financial centres such as New York, where their shares might be more highly valued.

Cambridge-based Arm, which makes chips for Apple’s iPhones, moved its main share listing to New York in 2023.

Fintech payments firm Wise last week said it would follow in Arm’s footsteps.

What started as a trickle has now become a flood.

Expert Charles Hall at stockbroker Peel Hunt notes there have been 30 bids for UK companies so far this year that value each of them at over £100million – the biggest being those for Alphaware and Spectris.

Buyers are paying an average premium of 43 pc to gain control of their targets.

‘This shows the scale of undervaluation in the UK,’ says Mr Hall, noting that British companies are more attractive to predators than investors.

‘If we want the UK equity market to thrive, an urgent rethink is required to ensure that UK capital backs UK companies.’

It used to be the case that British companies were at risk from US takeovers because the pound was weak against the dollar, making them cheaper for an American buyer.

‘But that’s not the case at the moment because sterling has been so strong over the course of this year,’ says Will Walker-Arnott at broker Charles Stanley.

It means, he says, that British companies are undervalued.

‘We’re in this doom loop where lower valuations breed more takeovers and more de-listings’ of shares from the stock market, Mr Walker-Arnott explains.

He blames the UK pensions industry for the growing exodus.

‘It’s highly fragmented, risk-averse, and until that changes we’re not going to get that fillip to UK valuations,’ Mr Walker-Arnott told the BBC yesterday.

Sir Keir’s Government wants pension funds to combine and use their enhanced clout to invest more in British companies to boost growth.

It has set them a target of investing 5 pc of their assets in privately owned UK companies. Labour is even threatening to force some of them to merge in order to cut costs and boost returns.

Sir Keir told Nvidia’s Mr Huang that he wanted Britain to be ‘an AI maker, not an AI taker’ as he announced plans to spend £1billion to boost the country’s digital infrastructure and computing power.

However, experts say much more is needed.

‘We have a very good history of building and starting companies here,’ says Eleanor Lightbody, boss of Luminance, which provides AI-powered systems for lawyers, but added: ‘There is some work that needs to be done to try to make them scale here and stay here.’

Who’s next?

We might deplore the trend for UK tech companies to be taken over, but the fact remains that if they are, shareholders stand to profit. Bidders have to pay a substantial premium over the share price before they wade in, if they are to win control – which means a nice gain for investors.

This can be as much as 50 pc depending on the price being paid.

You should not buy shares on bid hopes alone.

That’s because even when a potential purchaser says it might make an offer, a deal may not actually happen.

In these circumstances, some shareholders can be left out of pocket if the share price then falls as the would-be bidder pulls out.

‘Buying a company just for a bid is a mug’s game,’ says Russ Mould, investment director at AJ Bell.

Shares should be bought on the basis of what a company does, its competitive position, its financial strength and operational performance, and who sits on the board.

‘If a bid comes along, then all well and good, but ultimately the idea is to buy good assets,’ Mr Mould adds.

That said, here are some ideas for tech investors.

Oxford Instruments

Oxford Instruments fought off a £31 per share bid from Spectris – which itself is now the focus of a £3.7billion offer from Advent International – in 2022.

At the time, the company, which provides tech to a range of industries including pharmaceuticals, forensics and aerospace, traded at around £20 compared to today’s £19.50.

Mr Mould claims that could leave the company vulnerable to a takeover, saying Oxford Instruments ‘has a very strong global reputation in the science and meditech industries’.

Out of seven analysts, one rated the stock a ‘strong buy’, two said it was a ‘buy’ and two said to ‘hold’.

Renishaw

Renishaw supplies high-tech laser components used in drones and self-driving cars, as well as 3D printers that can make medical implants and false teeth.

The Gloucestershire firm, founded in 1973, put itself up for sale in 2021 but was unable to find a buyer.

Founder Sir David McMurtry, who died at the age of 84 last year, had made it clear he wanted to find a buyer that would be supportive of the business over the long-term and its UK manufacturing base.

Four out of eight analysts recommended that investors ‘hold’ Renishaw’s shares. Two rated it as a ‘strong buy’, one as a ‘buy’ and one as a ‘sell’.

GB Group

GB Group – an identity verification, location intelligence and fraud prevention firm – was targeted by a US private equity firm in 2022.

The board at the time said it would consider a £1.3billion offer from Chicago-based GTCR. However, the firms could not come to an agreement and the buyout group walked away without a deal.

Shares are down nearly 75 pc from their all-time high of 954p in 2021. ‘That could open a door for an opportunistic buyout from someone who is already strong in this area or maybe a player looking for greater European exposure,’ Mr Mould says.

Three analysts say GB is a ‘strong buy’ and seven rate it a ‘buy’.

Sage Group

Accounting software giant Sage Group is the biggest tech firm listed in London with a market capitalisation of around £12.3billion.

The Newcastle-headquartered business isn’t an obvious takeover target, but Peel Hunt recently said it is a ‘fantastic business’.

‘It is one of the few UK companies that has both the specialisation and the balance sheet to truly become a global leader in the accounting focused AI race,’ analysts at the investment bank said.

Sage Group is covered by 20 analysts: four rate it a ‘strong buy’, six say ‘buy’, eight say ‘hold’ and two recommend to ‘sell’.

Alpha Group

FTSE 250 firm Alpha Group is already ‘in play’ after business payments tech group Corpay made a preliminary offer.

Shares in the London-headquartered fintech hit an all-time high after the American payment giant signalled its interest, but it may climb even higher if a firm deal transpires.

Alpha Group rejected the offer but is holding talks with Corpay, recently extending the deadline for a final offer to July 7 from May 30.

According to LSEG, formerly known as Refinitiv, Alpha Group has just one analyst recommendation of ‘buy’.