This article is taken from the July 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

They’re not keen on D.H. Lawrence in universities these days. In fact, he’s not read much anywhere. Too prickly, by half. A member of the Awkward Squad. It’s not just that he is male and white, which can put a target on a fellow’s back — more that the Thought Police can’t place him. In an age of grimly cultivated identities, a protean spirit like Lawrence is unlikely to find much sympathy.

“Never trust the teller,” he wrote. “Trust the tale.” Yet too many people care for neither. “Bert”, as he was known, would have been indifferent to their indifference. He spent his life seeking liberation from the shackles of conventional thought.

Lawrence always was difficult to place. He wrote three of the greatest 20th century novels, many superb short stories, some marvellous poems and several plays, yet who was he? The son of a Notts miner, he mixed so freely with those born above his station that he popped up, disguised as Mark Rampion, in Aldous Huxley’s Point Counter Point.

A lifelong traveller, who wrote about the places he lived with an artist’s eye, he remained thoroughly English, though it was never a conventional Englishness. And he wrapped up his work, millions of words, before his 45th birthday. The sickly child was never going to make old bones.

So unschooled and repetitive is his fiction, which he never bothered to revise, that Evelyn Waugh thought he couldn’t write at all. It’s certainly true that Lawrence fits uneasily within the English tradition. At times it seems we are reading a Russian novelist in translation.

In Three Faces of DH Lawrence, on Radio 4, the writer was seen through the filter of sex, class and nature. Michael Symmons Roberts, the poet who presented the programmes, thought Lawrence was “genius or madman, take me or leave me”.

He was emphasising something Anthony Burgess noted. Lawrence’s poetry — by which Burgess meant all his writing, not just the verse — was “not the result of the creative process, it is the creative process itself”. That’s well put.

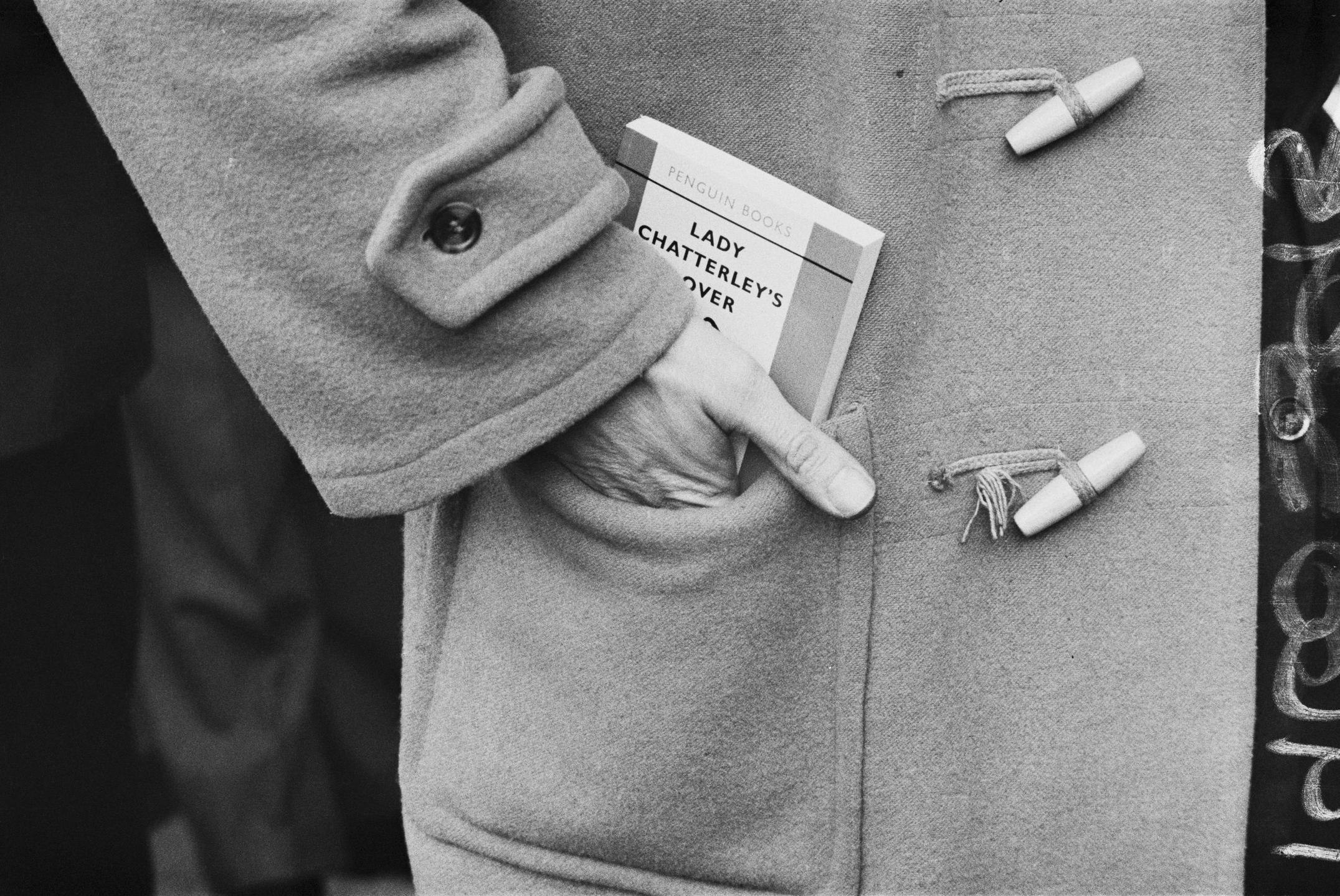

The phoenix, we were reminded, was the symbol of rebirth Lawrence claimed as his birthright. “The firebird” appears on copies of his novels, as A level sloggers of a previous generation may recall, and Flame Into Being was the title of Burgess’s book about him. It was a phrase Lawrence rang more than once, notably on the final page of Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

One of the academics on parade referred to middle-class readers who “substituted talk for feeling”, but Lawrence’s posthumous reputation was shaped by men like F.R. Leavis. A considerable figure in his Cambridge heyday, Leavis didn’t get a look-in here.

The truth is more cumbersome. Born into the old working class, with its unshakeable customs, Lawrence realised his interests did not correspond with those who shared the same streets. Eastwood, where he grew up, has never truly honoured him. “Not half the man his father was,” a miner once said.

So when Roberts referred to “the well-heeled chatterati”, he was maligning the people who enabled Lawrence to become the writer he wanted to be. His relationship with them may have been ambivalent, but they were his greatest benefactors.

Joan Bakewell was given another trot around the circuit of social hierarchy. When she first read Lawrence, as a schoolgirl in Stockport, she thought, “That’s my voice, I can hear that.” Chatterley, for people of her generation and background, “heralded a new kind of freedom”.

Lawrence spoke directly to thousands of young readers, some of whom became writers. David Storey, born in 1933, three years after Lawrence died, was also a grammar school-educated son of a miner. You can hear that voice in This Sporting Life, his celebrated first novel, and it is even clearer in Saville, winner of the 1976 Booker Prize.

It was a generous gesture, therefore, to spend three programmes with this unfashionable man. The most colourful endorsement came from Robert Lindsay, brought up an hour’s bike ride from Eastwood, who recognised the cracks into which the self-educated can fall.

Lindsay recalled how, in his teenage years, he spoke with a workman curious to know what writers did. The actor-to-be responded by reciting Lawrence’s poem, “Service of All the Dead”. That was a wonderful radio moment.

Slipping into the voice of his youth, for dramatic effect, Lindsay sounded authentic. But we could have done without the actor enlisted to impersonate Lawrence, whose voice was common. Lawrence could be rough. He was never common.

He was a good hater, somebody said. Inasmuch as he felt things in his blood, he was. But his best work tells a more compelling tale, one of affirmation. He dared to be truly free, in defiance of those -isms and -ologies that seek to enslave us. May his voice continue to be heard, in all its ruggedness and complexity.