Jamie Oliver‘s admission this week that his wife Jools is neurodivergent—three months after revealing some of their five children have also been diagnosed—has prompted a torrent of debate among readers.

Speaking to Davina McCall on her Begin Again podcast, the 50-year-old chef described his wife of 24 years as ‘the rock’ of the family.

‘She’s got incredible instinct, she’s incredibly kind, very funny. I love her to bits,’ he said.

‘I can’t really talk for her but she has neurodiversities that make her life really interesting and really challenging.’

Oliver, who has previously spoken about his own dyslexia, also joked about the impact of multiple diagnoses at home: ‘Imagine four neurodiverse people at the dinner table trying to get their point across.’

The revelation has divided opinion online, with many listeners questioning what the label means.

‘We all are [neurodivergent]! This is getting ridiculous,’ wrote one Daily Mail reader, responding to the story.

Another commented: ‘Of course she is, everyone is nowadays! Why is everyone in a rush to go out and get a diagnosis? It’s just your personality.’

Jamie Oliver has opened up on his ‘very neurodiverse family’, revealing that understanding how their children see things differently allows him and wife Jools to be ‘better parents’

Jamie said that he and Jools discuss their children in bed every night and have ‘learnt to understand that their behaviour is because they’re seeing things differently’

Others were blunter still. ‘Isn’t it just poor behaviour being excused because of a label?’ asked one.

‘Everyone now needs a label. What rubbish,’ said another, while one sceptic dismissed it as ‘the latest must have.’

The reaction reflected a common sentiment: that while more people than ever are being diagnosed, many still don’t understand what the label neurodivergent actually means.

To get to the bottom of the debate, we turned to the experts.

The word was first popularised in the late 1990s by Australian sociologist Judy Singer, who argued that differences such as autism and dyslexia should be seen as part of the natural spectrum of human brains rather than medical defects.

Today it is used as an umbrella term for a range of conditions, including autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyslexia—which affects reading, writing and spelling—and dyspraxia, which causes problems with motor co-ordination.

Crucially, it is not a diagnosis in itself but a way of describing people whose brains function differently from what is considered ‘typical’.

Jamie himself has dyslexia, which he says left him feeling ‘worthless, stupid and thick’ at school.

He has spoken about how his own struggles motivated him to campaign for better food education and to push for earlier screening in schools.

He and Jools have five children—daughters Poppy, 23, Daisy, 22, and Petal, 16, and sons Buddy, 14, and River, eight.

He has said that within the past year some of them have been diagnosed with dyslexia, ADHD and autism spectrum disorder, though he has not revealed which child has which condition.

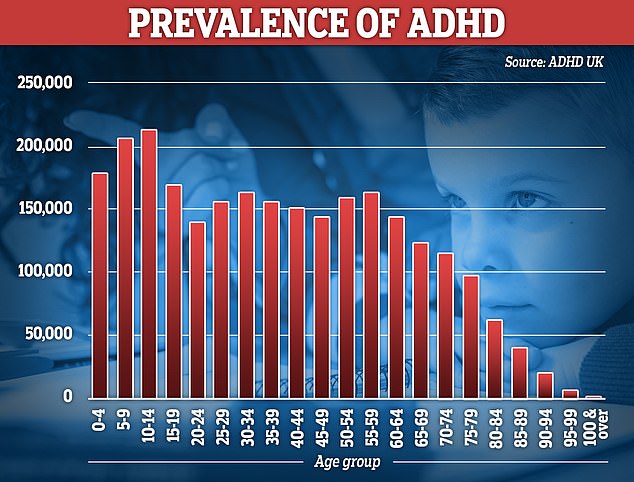

Around 15 per cent of the world’s population are thought to be neurodivergent. In the UK, about one in 100 people are on the autism spectrum, and roughly four per cent have ADHD. But the numbers are rising.

NHS figures published this year showed more than 549,000 people in England were waiting for an ADHD assessment at the end of March 2025—up from 416,000 the year before.

Of these, around 304,000 had been waiting at least a year, and 144,000 for two years or more.

Demand has surged, particularly among children and young adults.

Experts say conditions often overlap. Research suggests that between 50 to 70 per cent of people with autism also have ADHD.

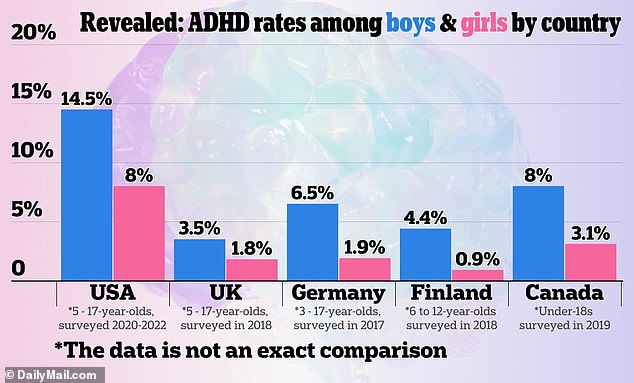

How ADHD rates compare between countries, according to US official sources

The increase has been reflected in celebrity culture. Alongside Oliver, other public figures who have spoken about being neurodivergent include climate activist Greta Thunberg, presenter Sue Perkins, comedian Rory Bremner and Love Island star Olivia Attwood.

But while many celebrate greater openness, some experts are uneasy about the way the term is spreading on social media.

Consultant psychiatrist Dr Dinesh Bhugra, writing in the Daily Mail, said: ‘I applaud people talking openly about their mental health struggles.

It helps to break down some of the stigmas and misconceptions that surround the subject.

‘But I also have concerns. I’d argue this new trend somehow makes these conditions seem not simply just fine, but something you might aspire to have.

And I worry that some of these people don’t have genuine disorders at all, they only believe they do.’

He warned that influencers can encourage teenagers to believe everyday traits—being forgetful, restless or disorganised—are symptoms of a medical condition.

‘Being easily distracted, or drifting off while someone’s talking to you; hating being in busy, noisy environments; forgetting your keys. These are normal feelings, emotions and actions, part of the hugely diverse spectrum of being human.’

Former Bake Off host Sue Perkins (left) last year shared that she had been diagnosed and that ‘suddenly everything made sense – to me and those who love me’. Love Island’s Olivia Atwood (right) said ADHD made her ‘constantly overwhelmed’

Dr Bhugra, a former president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists added: ‘I worry we’re creating a generation that believes every bad day or unpleasant emotion requires medical intervention to help them cope.

‘And it is also a green light to behave in an unusual manner—it can’t be bad timekeeping or rudeness if it’s actually ADHD or an autism spectrum disorder.’

The rise of neurodivergence as an identity has been empowering for many. Badges and T-shirts emblazoned with slogans such as ‘neurodiverse squad’ have become popular, while online communities offer solidarity and advice.

Fresh concerns have also been raised about the reliability of adult ADHD tests.

A recent analysis of nearly 300 studies by scientists in Scandinavia and Brazil found that in almost half, researchers failed to rule out other conditions such as depression that can mimic ADHD symptoms.

In some cases, patients had even diagnosed themselves or used computer programmes rather than undergoing assessment by a trained psychiatrist.

Dr Julie Nordgaard, consultant psychiatrist at the University of Copenhagen and a co-author, warned: ‘In psychiatry, we really need that all diagnoses, not just ADHD, are made with the same uniform criteria and by trained professionals.

‘Otherwise, we cannot rely on the results or compare them across studies.’

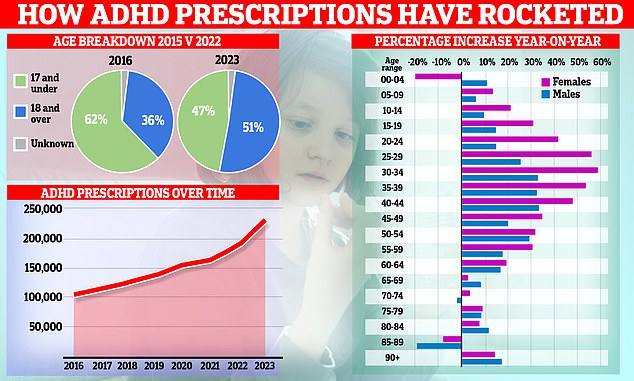

Fascinating graphs show how ADHD prescriptions have risen over time, with the patient demographic shifting from children to adults with women in particular now driving the increase

Her colleague Dr Mads Gram Henrikson added: ‘Especially in a situation where a diagnosis such as ADHD in adults is increasing, we need to be very thorough and have a solid foundation.’

A separate study published in March in BMJ Mental Health suggested the boom in ADHD diagnoses is being fuelled by social media.

Researchers at Aston University and the University of Huddersfield found prescriptions for ADHD drugs in England had risen nearly a fifth year-on-year since the pandemic, with some areas reporting increases of more than 50 per cent.

They warned that platforms like TikTok and Instagram are awash with videos promoting everyday quirks—from ‘mystery bruises’ to ‘coming across as a flirt’—as possible signs of ADHD, sowing misinformation that may push people to seek diagnoses.

‘While social media has been instrumental in spreading ADHD awareness, it is crucial to approach the information with caution, as the accuracy and reliability of the content can vary significantly,’ the authors wrote.