Four years ago, Louis-Henri Mars went deep inside the Port-au-Prince stronghold of two of Haiti’s most-feared gang leaders, known as Barbecue and Iskar.

As he prepared to sit down and speak, Mr. Mars reminded himself of some of the principles he had developed when approaching gang members in the past: See them for their humanity, not only for their violent actions, and be open and truthful about what you are seeking.

Mr. Mars had founded Lakou Lapè – “Peace Yard” in Haitian Creole – a peace-building nonprofit, in 2012. When he visited the gang leaders in 2021, he had a radical proposal for achieving unity and curbing Haiti’s unrest. “Invite members of the business elite [into your community] for a day or two,” he told Barbecue and Iskar. “They don’t understand you, because they’ve never lived in poverty.”

Why We Wrote This

Violence has dogged Haiti for generations. A former businessman is working to build social bridges toward peace.

Restoring trust in Haitian society is essential to breaking the cycle of violence that has dogged the country for generations, says Mr. Mars. His organization, one of the few peace-building groups still operating in Port-au-Prince as local and international organizations have shuttered, aims to unite Haitians from opposite ends of society through workshops, conflict mediation, and youth empowerment programs.

Barbecue (Jimmy Chérizier) and Iskar (Iskar Andrice) had been calling for war against the country’s elite. Only an armed revolution, the two men argued, could persuade the rich to share with poor people. Yet here they were, listening to Mr. Mars – a former business executive – encouraging them to build social bridges.

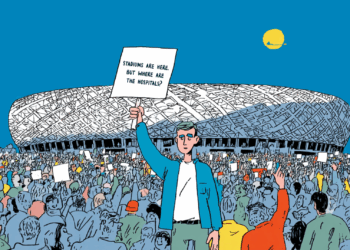

“I tell our donors we don’t just need roads or electricity grids,” Mr. Mars says. “We must build relationships. We’ve been looking in the wrong direction for too long.”

Culture shock

As the son of a Haitian diplomat, Mr. Mars grew up between embassies – from Paris to Washington, Rome to London. The swift pace of changing languages and traditions helped him learn early on how to navigate cultural divides.

Culture shock came later, when he returned to Haiti as a young adult in 1977 and was taken aback by the vast inequalities he encountered. His concerns about Haiti’s divisions only deepened in 1991, when a military coup halted his electronics and leather business in Port-au-Prince. That coup was the latest in a series of crises after decades of authoritarian rule, paramilitary repression, and political assassinations in the late 1980s.

“What was it about this country that made it trapped in this endless cycle of unrest?” Mr. Mars recalls wondering.

A gathering in the mountains

Mr. Mars immersed himself in researching how peace is achieved. He trained with mediators from the Irish-British peace process and studied peace in Northern Ireland.

Before long, Mr. Mars started bringing together Haitian business leaders and low-ranked gang members at retreat spaces to share rooms, meals, and their life stories. He formed peace and dialogue committees, in which residents from communities across the capital discuss subjects such as curbing guns or domestic violence. He facilitated discussions among armed groups, sometimes resulting in temporary ceasefires or brief reductions in shootings.

“What I admire about [Lakou Lapè] is their resilience,” says Vélina Élysée Charlier, a human rights activist with NouPapDòmi (“We Won’t Sleep”), an anti-corruption organization in Haiti. “I don’t usually like that word. It’s overused for Haitians, as if we’re expected to endure anything forever. But for them, I use ‘resilience’ as a compliment.”

“They stay close to the community, which keeps their work relevant,” she adds.

Mr. Mars recalls one gathering in 2009, high in Haiti’s mountains, where he and visiting Irish mediators brought together rival gang members. The workshop nearly collapsed when one gang leader discovered that a police officer would participate. “It took … mediation skills to stop him from walking out,” Mr. Mars recalls with a smile.

That man, Jean Claude Joseph, eventually laid down his guns after years of workshops and training sessions. In 2012, Mr. Joseph helped Mr. Mars start Lakou Lapè.

Healing generations of pain

Drawing on practices developed by a U.S. university after the 2010 earthquake, which flattened or damaged large swaths of Haiti, Mr. Mars made healing circles a cornerstone of his retreats. Participants could “cry together, encourage each other, and hold each other accountable,” says Mr. Mars, cognizant of Haiti’s long fight for independence and its history of slavery, natural disasters, and extreme inequality.

Gangs control about 95% of the capital. The number of Haitians displaced by violence has more than tripled since December 2023, growing to 1.3 million people today.

Barbecue, the gang leader, now heads a powerful alliance, Viv Ansanm, which has repeatedly shut down the country’s main seaport and airport, carried out massacres, and burned down homes. His professed “war against the elite” has escalated into what seems like a war on the entire population. It’s troubling, but Mr. Mars does not see this development as a failure of his peace-building model. His work could take decades to reap significant results.

But impunity is not an option. “The gangs have murdered, kidnapped, raped, expelled, and burned,” Mr. Mars says. “If victims aren’t compensated and their [experience is] not addressed, the violence will never end.”

Ms. Charlier, from the anti-corruption organization, agrees that dialogue and relationship-building alone are not enough. “Peace can only be achieved when justice is served,” she says.

In Mr. Mars’ workshops, business leaders and young people from high-unemployment neighborhoods often meet for the first time. “Mars is one of those rare people who is accepted in both worlds: the business sector and the communities,” says Geoffrey Handal, a fifth-generation head of his family’s shipping and logistics conglomerate, who began attending Mars’ workshops in 2020.

There, he met Jean Gilles Bernard Camille, a young Peace and Dialogue facilitator who spoke of the stigma he faced growing up in Barbecue’s stronghold. When Mr. Camille later pitched a business idea – a tilapia farm in above-ground basins – Mr. Handal decided to invest.

The venture soon became more than a financial project. Mr. Handal describes Mr. Camille as an “ambassador,” showing his community they were wrong in their blanket mistrust of the business elite. For Mr. Camille, it has been an opportunity to prove to Mr. Handal and his peers that someone from a “hot” neighborhood can deliver on his promise.

“Repaying that trust is what keeps me going,” Mr. Camille told Mr. Handal recently, even as a lack of security forced the project to stall.

That, according to Mr. Mars, is what peace-building looks like: developing mutual respect and a shared vision for the future. But it takes time, is hard to measure, and is sometimes difficult to explain to the international community.

Until recently, Lakou Lapè relied mostly on funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development. With the Trump administration’s freeze on almost all foreign aid, the group has paused its programming while it seeks sources of financing. Mr. Mars also has had to step back from some day-to-day tasks to deal with a health challenge.

Change at the local level

The Transitional Presidential Council, appointed a year ago to steer Haiti toward elections, has been hampered by internal divisions and corruption allegations. The Aug. 7 appointment of businessman Laurent Saint-Cyr as council president reignited threats from Barbecue to overthrow the government. The gangs and marginalized residents doubt that a government historically dominated by wealthy people can deliver real change.

Days after Mr. Saint-Cyr’s appointment, the government announced a three-month state of emergency in Haiti’s central region. By September, it had been expanded nationwide.

Mr. Mars’ dream is to see a gang-controlled neighborhood reclaimed by civilian leadership. He knows it’s time to hand over the reins to the new generation of peace-builders he has helped shape.

Four years after Mr. Mars’ meeting with Barbecue and Iskar (who was killed by an unidentified shooter in 2023), life in Delmas 2, the neighborhood ruled by Barbecue, is facing unprecedented violence. But in a room tucked within a maze of makeshift homes sits one of Mr. Mars’ peace-builders. For four years, Derlineda Louis Jeune has been a member of a peace and dialogue committee facilitated by Mr. Camille.

Ms. Jeune moved here in 2021, after violence displaced her from her home community. She plans to study law and then become a leader for change, working with young people.

From her perspective, “Peace is possible in Haiti.”