This piece has been copublished with Drop Site News.

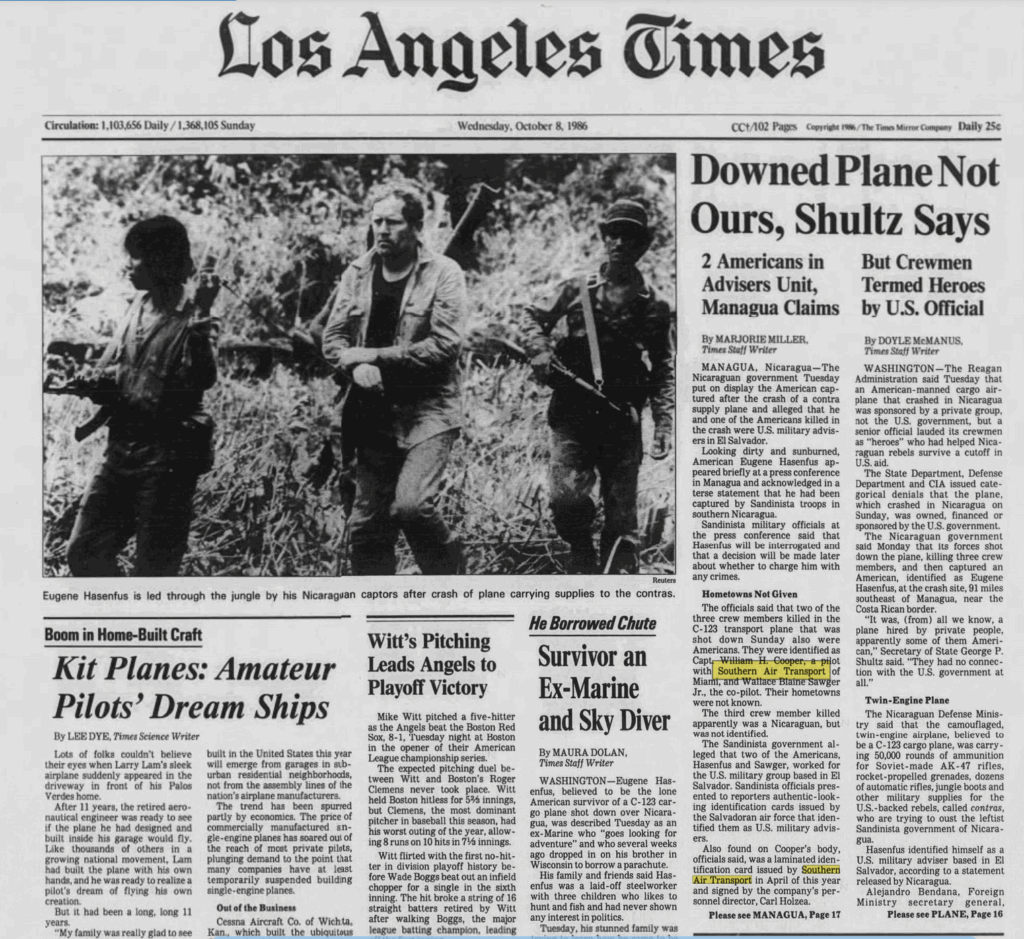

When a Southern Air Transport plane was shot down over Nicaragua in October 1986, the world got a rare window into U.S. government covert activity. Southern Air Transport was founded as a small cargo airline in 1947, the same year the Office of Strategic Services evolved into the Central Intelligence Agency as the U.S. pivoted to its Cold War posture. The agency owned the airline outright from 1960 until 1973, at which point it was sold to the same man, Stanley Williams, who had run the company since the Kennedy administration.

The downing of the plane and the testimony of its lone survivor, Eugene Hasenfus, pulled a string that eventually unraveled the scandal known as Iran–Contra. Using Southern Air Transport planes, the CIA was shipping weapons to Iran, using Israel as a middleman, and deploying the profits to arm the Contras against the leftist Nicaraguan government.

None of it was legal, and Southern Air Transport was getting too hot. In 1995, the company relocated its headquarters from Miami, Florida, to Columbus, Ohio. The company rebranded by flying imported shipments of clothing from China. But for three years in Columbus, the airline was dogged by rumors it had been—or was still—involved in drug smuggling.

According to the veteran Columbus journalist Bob Fitrakis, who provided his historical reporting on the topic to Drop Site and The American Conservative, investigators in both the Franklin County Sheriff’s Office and Ohio’s Office of Inspector General were looking into Southern Air Transport amid ongoing public scrutiny of the Iran–Contra affair—and sources in both offices identified Jeffrey Epstein as having a pivotal role in relocating the planes.

At the time, Epstein was a relatively obscure financier managing the money and real estate investments of the Ohio-based fashion and retail mogul Leslie Wexner. Under his stewardship of the Wexner empire, the planes that previously carried arms to Iran and Nicaragua were repurposed to deliver clothes to feed Wexner’s network of retail chains, including Victoria’s Secret and Abercrombie & Fitch.

Southern Air Transport abruptly declared bankruptcy on October 1, 1998—exactly one week before the CIA Inspector General released its official findings on the Iran–Contra affair, linking the airline to allegations of Contra cocaine trafficking from Nicaragua. Per Fitrakis, under pressure from the governor’s office, Ohio officials dropped their inquiries, meaning that Epstein’s role never became public.

How did Epstein end up moving the former Contra planes to Columbus? Answering that question—or at least getting close—requires a closer look at the men behind the scandal that defined the second half of the Reagan administration and gave the public the clearest look inside the U.S. government’s clandestine global operations in a generation or more. Like a spy-service Forrest Gump, Jeffrey Epstein can be found there every leg of the way.

“Finding Hidden Money”

In 1981, Jeffrey Epstein resigned from Bear Stearns amid suspicions of insider trading, and began traveling regularly to London, where he grew close with the family of Douglas Leese, a British businessman with a long career in auto and aerospace manufacturing. Epstein became Douglas Leese’s protégé and fast friends with his sons Nicholas and Julian, according to a podcast interview later given by the latter. After the Second World War, Douglas Leese had been managing director of his father’s company, Cam Gears, a steering-gear manufacturer that supplied Jaguar, Ford, Nissan, and other global auto brands. In 1965, the company was sold to TRW, a U.S. aerospace conglomerate known for satellites and intercontinental ballistic missiles.

1979 was a revolutionary year in the Persian Gulf. Saddam Hussein became president of Iraq and swiftly executed and imprisoned his political rivals; the people of Iran overthrew the CIA-backed shah. During Iran’s revolution, university students seized the U.S. embassy in Tehran and took Americans as hostages, leading the U.S. to impose harsh economic and military sanctions.

The CIA planned to fuel a war between Iran and Iraq to ensure neither Hussein nor Ayatollah Khomeini could gain control of the Strait of Hormuz while keeping the Soviet navy out as protector of the Gulf. But the hostage crisis had added a wrinkle to their plans. After the 1979 revolution, the U.S. was prohibited from selling weapons to Iran, as any overt weapons deals would violate an official arms embargo and undermine President Ronald Reagan’s public position that America did not bargain with terrorists.

Instead, in a strategy aimed at reducing Soviet influence with Iran, the CIA tacitly supported weapons sales from China. Beijing began shipping armaments to both Iran and Iraq in 1980. In spring 1983, Iran signed a $1.3 billion arms deal with China. These weapons were supplied in part by the Chinese manufacturing conglomerate Norinco using British Hong Kong as the transshipment point.

Douglas Leese at the time owned a Bermuda-based holding company, Lorad. Soon after the Iran arms deal was signed, a new Lorad entity, a shell company called Norinco Lorad, was formed in Bermuda; a Hong Kong trading company called Lorad Far East followed a few months later.

Leese’s exact role in China’s weapons sales has never been made public. But in 1995, a British MP—George Galloway—alleged Leese had clandestinely funded Middle East arms deals using a Bermuda bank. That year, the owners of British retail chain Littlewoods raised alarm bells about Leese’s arms trafficking ties, after the company received a proposal for Norinco to sell washing machines to Littlewoods and weapons to Lorad.

Two years later, in a U.S. civil complaint against the Littlewoods owners, Leese claimed his work concerned “highly-sensitive” projects “believed to be classified by the Department of Defense and other agencies of the United States government.”

Meanwhile, the CIA prepared its own covert pipeline to ship American-made weapons to Iran. In the fall of 1980, the FBI placed Cyrus Hashemi, an Iranian banker, under extensive electronic surveillance, recording tens of thousands of conversations over a five-month span. The tapes revealed that John Stanley Pottinger, Hashemi’s attorney, was helping the Iranians circumvent the arms embargo using phony invoices and overseas shell companies. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee later found that the CIA was involved in planning the arms deals and had met with Hashemi in Pottinger’s office.

Pottinger, it turns out, was working together with Epstein in New York. Pottinger had previously served as an assistant attorney general under President Richard Nixon; now, he joined up with another “crook,” and the two men rented a penthouse office together on Central Park South, according to the New York Times. The Times reported that Pottinger and Epstein were pitching “tax avoidance” strategies for wealthy clients, and noted that the business partnership was “short-lived.” In 1984, Pottinger was identified in a federal indictment against Hashemi for illegal arms exports, and Hashemi fled to England.

Pottinger escaped prosecution after the FBI’s incriminating tapes of his conversations mysteriously disappeared; he went on to make a fortune on real estate deals in the 1980s, and became a New York Times’ bestselling novelist. His 2024 Times obituary reports that his final spy thriller remains unpublished. Hashemi died in 1986 after being infected with “a rare and virulent form of leukemia” that was diagnosed only two days before he died. (His death was later alleged to be foul play.)

After Hashemi’s indictment, another player stepped in to broker access to Iran for the Americans: the Saudi arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi, uncle of slain Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi. In July 1985, Hashemi, Khashoggi, and Israel’s Prime Minister Shimon Peres had met secretly in Hamburg, West Germany, to hatch a plot: With CIA director William Casey’s blessing, the U.S. would ship the weapons to Israel, Israel would sell its own weapons to Iran, and Washington would commit to replenishing Israel’s stockpile later.

At some time in the 1980s Epstein obtained an Austrian passport with a false name and an address in Saudi Arabia. After his arrest in 2019, U.S. authorities discovered it in a safe in his New York mansion. At a bail request hearing, Epstein’s attorneys claimed it came from a “friend,” intended to conceal his Jewish identity in case of a potential kidnapping while traveling. Seven Americans, including a CIA officer, were kidnapped in Lebanon between 1984 and 1985, and discussions emerged around an “arms-for-hostages” trade with Iran.

After Peres agreed to facilitate Khashoggi’s shipments to Iran, the logistics were handled by Israeli military intelligence. Epstein’s close friend and confidante, Ehud Barak, was the head of Israel’s military intelligence directorate during the planning phases, from April 1983 to September 1985. He left the position one month after the first arms shipment was completed. To this day, Barak maintains that he was introduced to Epstein by Shimon Peres at a “public event” in 2003, after he left government service. Barak has also falsely claimed that he barely knew Epstein. Whether they truly met before 2003 is unknown.

The Israeli arms pipeline depended on a fragile trust. The Israelis wanted cash up front, but the Iranians would only pay after the weapons were delivered. Acting as the “bank,” using accounts at the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI), Khashoggi advanced tens of millions of dollars in credit so that weapons could move even when the parties did not trust each other. Ghaith Pharaon, a Stanford-educated businessman close to the Saudi royal family, acquired regional banks and distressed insurance companies in the U.S., to loop BCCI into U.S. financial markets.

The CIA shielded BCCI from federal investigators to conceal the money trail to their illicit arms deals. BCCI operated as a Cayman Islands entity structured as a charitable trust, funneling capital into employee-benefit funds and philanthropic foundations in the UK and South Asia, which in turn owned a plethora of shell companies. The shells served as parking lots for BCCI assets, and conduits for transactions that needed to be hidden from the balance sheets of the bank’s local branches around the world. In practice, BCCI’s founder Agha Hasan Abedi and his small circle of deputies controlled the entire flow of money with almost no outside oversight.

With each successful delivery, an American hostage was freed in Lebanon, and the intermediaries earned handsome commissions. Once arms profits had been cycled through BCCI’s network, real estate was a method of transforming suspicious cash flows into legitimate sales and rental income, while obscuring the “true” ownership behind layers of shells. BCCI was heavily involved in real estate lending and property purchases through shells and nominees and Khashoggi himself had massive real estate holdings worldwide, including hotels, ranches, mansions, and commercial properties. Pottinger’s obit reports he made a fortune in real estate in the 1980s.

Decades before Epstein became a household name, former Israeli intelligence officer Ari Ben-Menashe wrote in his 1992 memoir that Barak feared Peres or the Americans would discover the slush fund bank accounts where the arms profits were hidden and take the money for themselves. Ben-Menashe claimed that Barak arranged for the media mogul Robert Maxwell, Ghislaine Maxwell’s father, to launder the Iran weapons profits through his companies’ accounts and hide the money in Soviet banks where they could not be touched by the Americans.

In 1991, four years after Iran–Contra, Maxwell disappeared from his 180-foot yacht, the Lady Ghislaine, while it cruised off the Canary Islands. Hours later, Spanish authorities recovered his body from the Atlantic. Maxwell’s media empire was collapsing under a mountain of debt, and he was secretly siphoning hundreds of millions of pounds sterling from his companies’ pension funds. When investigators began untangling the books after his death, they found nearly half a billion pounds missing, and possibly more.

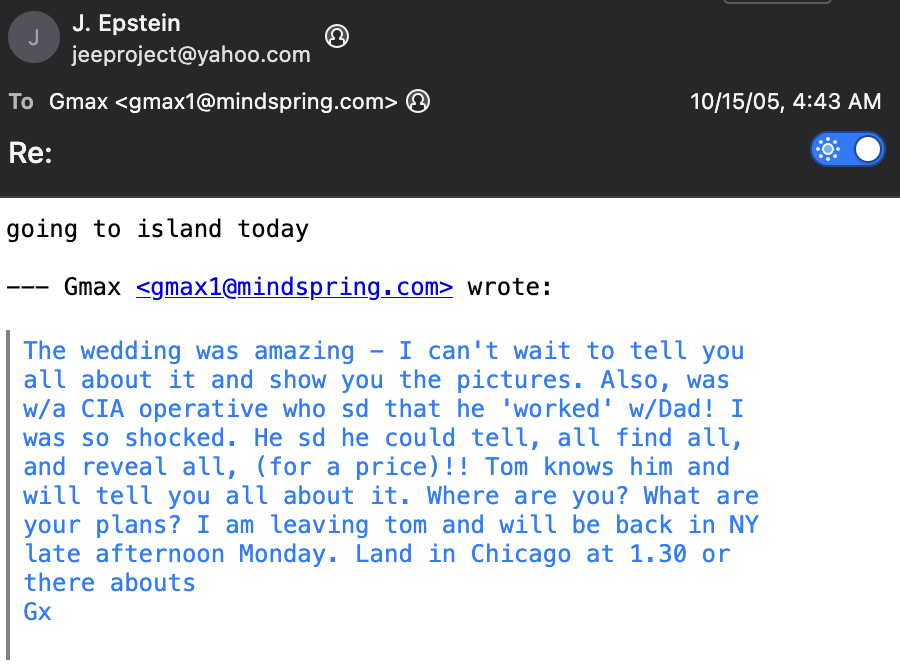

An email obtained from Epstein’s Yahoo! inbox, dated October 15, 2005, suggests Ghislaine Maxwell was trying to purchase information about her father’s missing fortune from a CIA operative. Maxwell emailed Epstein excitedly while visiting Bhutan for the wedding of Princess Chimi Yangzom Wangchuck. She wrote Epstein, “The wedding was amazing…Also was w/a CIA operative who sd that he ‘worked’ w/Dad! I was so shocked. He sd he could tell, all find all, and reveal all, (for a price)!!”

Epstein often made vague boasts about being a “financial bounty hunter” who tracked down “hidden” money. In 1987, while Robert Maxwell was allegedly “hiding” money from arms deals, Epstein bragged to a journalist about “finding” money for Adnan Khashoggi in such detail, the journalist thought Epstein “might be in the business of hiding as well of finding it.”

“Logistics Man”

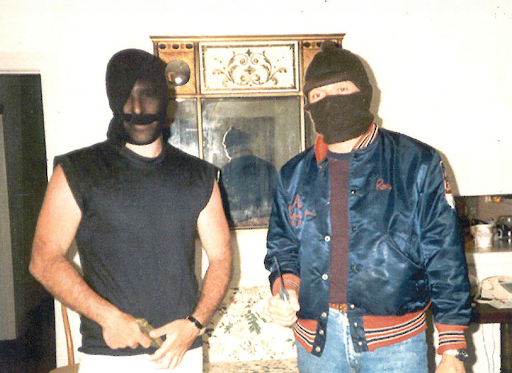

After the Southern Air Transport plane carrying Hasenfus was shot down over Nicaragua on October 5, 1986, the Iran–Contra scheme began to unravel. On October 9, Hasenfus confessed in a conference before the world’s press that he was working with the CIA to ferry weapons to the Contras, secretly backing their war against Nicaragua’s leftist government. U.S. officials quickly denied Hasenfus’s confession, saying he was on a “private” mission. (Hasenfus died in late November of this year.)

Southern Air Transport, a CIA front, was not only shipping weapons to the Contras; the planes were also carrying weapons to Israel, to fuel the brutal war between Iran and Iraq. Just weeks after Hasenfus’s press conference, SAT flew its last Iran–Contra mission from Tel Aviv to Tehran, carrying 500 U.S.-made anti-tank missiles.

One month later, a Lebanese newspaper broke the story that the Iran arms sales were part of a secret deal in exchange for the release of Americans taken hostage in Lebanon. One of the hostages, the CIA officer William Francis Buckley, had been killed in captivity. American officials confirmed the reports, spurring an investigation by the Justice Department. Within weeks, the U.S. attorney general was forced to step in front of news cameras and acknowledge that profits from the Iran arms sales were secretly fueling the Contras. Soon afterwards, newspapers reported that the same SAT planes had been smuggling cocaine from Nicaragua and Colombia into the United States.

The story became a major political scandal in the U.S. In December 1986, reports emerged that Khashoggi had received tens of millions of dollars for brokering the weapons shipments. Within one month, in January 1987, Khashoggi’s U.S. holding company filed for bankruptcy; BCCI’s front man, Ghaith Pharaon, sold off his bank assets shortly thereafter. SAT, which was now flagged in DEA databases for suspected cocaine trafficking, pivoted to highly publicized famine relief missions in war-torn “hot spots” in Africa with the United Nations and the World Food Programme.

Within months, Epstein appeared to be absorbing lessons from the era’s covert financial engineering. In 1987, as the Iran–Contra operation was unraveling, he emerged as a key financial advisor to the retail and fashion kingpin Leslie Wexner. Epstein became an officer of several Wexner shell companies, while later leading the same family office that ran Wexner’s philanthropic foundation—an architecture that, like BCCI’s, placed a charitable vehicle at the apex of a vast web of companies. That same year, Wexner established The New Albany Company, a massive real estate development project to build a new city in a rural area outside Columbus, Ohio.

Later in 1987, Epstein reprised a basic BCCI tactic: use a regulator-friendly narrative to gain control of a financial institution, then pillage its assets. Just as BCCI used Ghaith Pharaon as a nominee to acquire banks and insurance companies, Epstein helped Steven Hoffenberg persuade Illinois regulators to approve the purchase of two ailing insurers by promising a $3 million capital injection from Towers Financial, Hoffenberg’s debt-collection agency. The money never arrived—after closing the sale, they used the insurers’ bonds as collateral to finance hostile takeovers of two struggling airline companies, Pan Am and Emery Worldwide.

Towers Financial became a slush fund that subsidized Epstein’s lavish lifestyle in New York. After it collapsed in 1993, Hoffenberg pleaded guilty to defrauding investors out of nearly half a billion dollars in what the SEC at the time called the largest Ponzi scheme in U.S. history. He was sentenced to twenty years in prison; he later described Epstein as his “co‑conspirator,” though Epstein was never charged.

The stolen money vanished. In 2002, Hoffenberg alleged that Epstein hid $100 million in offshore accounts while working with prosecutors to scapegoat Hoffenberg and other Towers Financial executives. “Epstein certainly did secretly cooperate against Hoffenberg and gave at least three interviews to prosecutors,” Vicky Ward reported for Rolling Stone, adding that “had the case gone to trial, a source with knowledge says it would have likely turned out far worse for Epstein than for Hoffenberg.”

In that 2002 interview, Hoffenberg also helped to piece together part of Epstein’s past; he told Ward that he believed it was Douglas Leese who had introduced Epstein to Adnan Khashoggi. When Ward asked Epstein to respond to Hoffenberg’s claims, Epstein said he didn’t know Leese and furiously rejected any association with the Towers Financial fraud.

Epstein threatened to sue Ward if her story insinuated his culpability in the Ponzi scheme—and, when Vanity Fair attempted to revive the story in 2007, private messages in his Yahoo! inbox show that Epstein drafted letters to Ward’s editor, Graydon Carter, railing against her piece and threatening again to sue for defamation. In drafts sent to himself by email, he wrote to Carter, “I am writing to you to give you the opportunity , while ti [sic] still exists to correct a wrong.” (Epstein may have been counseled against sending those emails; Carter told Drop Site he never received them.)

Epstein lied to Ward about his ties to the Leese family: He knew both of Douglas Leese’s two sons very well. The elder brother, Nicholas, wrote a bawdy letter in Epstein’s 50th “birthday book” containing anecdotes of escapades—including description of a sexual assault framed as hijinks gone wrong—in Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur, and Tramp nightclub in London.

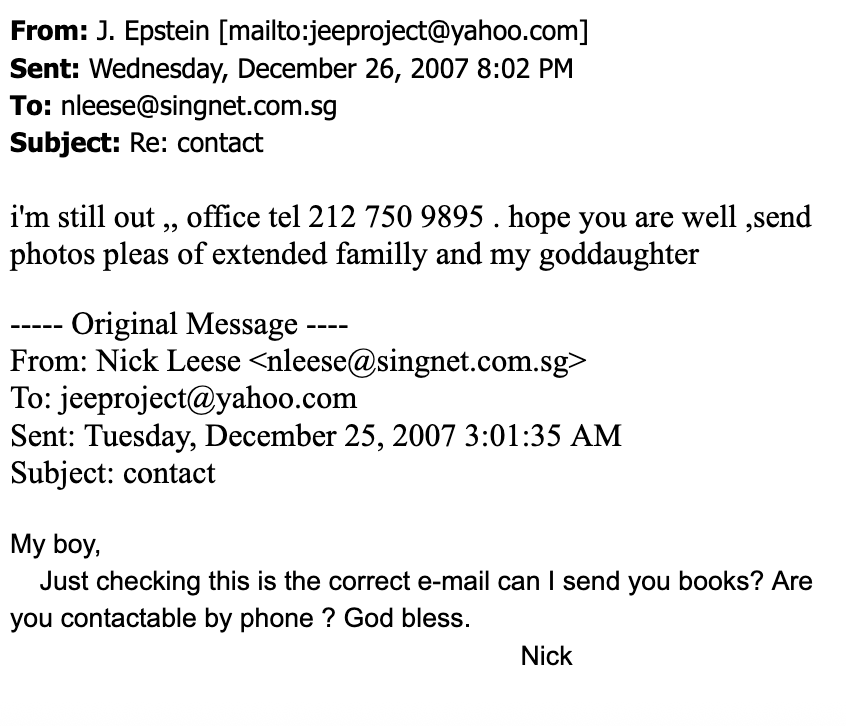

The relationship between Epstein and the Leeses remained intimate over the years. According to the emails obtained by Drop Site, Epstein was the godfather of Leese’s granddaughter, and both brothers affectionately addressed Epstein in their emails as “my boy.” In 2007, at Epstein’s request, Julian Leese sent a collection of family photos, writing, “Always thinking of you and the old days.”

Julian Leese briefly worked as an intern at Towers Financial after graduating from the University of Salford; he told journalist Tom Pattinson that his father had supported Towers Financial by introducing Hoffenberg to people in his circle. In his final recorded interview, Julian claimed his father sold radar equipment, not weapons, and admitted that Epstein occasionally advised his father and was present at some of his business meetings. In the same interview, he claimed Epstein and his father had a falling out around the early ’80s, over Epstein’s abuse of his father’s expense accounts—a claim that raises more questions than it answers. (Julian died in 2024.)

“Corruption All Over the City and State”

While the Towers Financial Ponzi scheme was taking off, Epstein had risen to the status of chief financial adviser to Wexner’s business empire, built around his clothing company The Limited, headquartered in Ohio. Epstein also became the financial engineer and trusted fixer behind Wexner’s massive real estate development project in New Albany. By 1991, the New York Times described Epstein as “president of Wexner Investment Company.” Epstein’s sudden rise to influence baffled Wexner’s old advisers, who were pushed out of Wexner’s organization one by one.

Although Epstein is sometimes described as a con artist who beguiled a naïve billionaire—the New York Times called Wexner “his most significant mark”—the series of events leading up to Epstein’s takeover of Wexner’s fortune paint a very different picture.

In 1991, the Columbus Police Department was investigating the mob-style assassination of Arthur Shapiro, an attorney whose firm worked for The Limited. In March 1985, Shapiro was due to testify before a grand jury in a major tax evasion case—but the day before his testimony, he was shot twice in the head, at point-blank range, in his car outside a Columbus cemetery.

Berry Kessler, an accountant, was considered the prime suspect in Shapiro’s murder; he was later convicted for two unrelated murder-for-hire plots, and sentenced to death. Another Columbus man sharing his last name, John “Jack” Kessler, was Wexner’s partner in The New Albany Company, where Epstein became co-president.

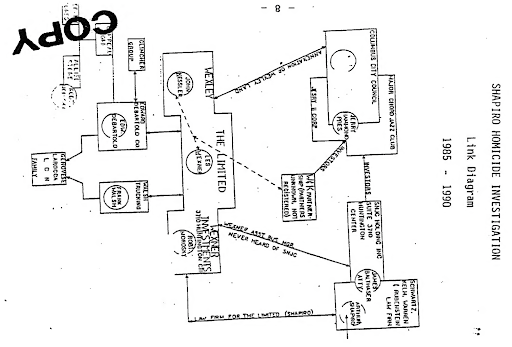

On June 6, 1991, a Columbus police analyst submitted an internal memo that suggested Wexner’s business was connected to organized crime. The memo identified several Wexner corporate entities formed by the slain lawyer’s office, some of which appeared to be linked to Wexner’s New Albany property development. Epstein’s name later appeared as an officer of some of these same companies when they were dissolved a few years later.

In July 1991, one month after the Shapiro murder memo was submitted to the police department’s Intelligence Bureau commander, Wexner signed a document giving Epstein power of attorney to act on his behalf in all affairs, effectively handing Epstein personal control of his vast fortune, and the right to sign property transactions on Wexner’s behalf. The Columbus Police Chief ordered the memo destroyed. Ohio’s former Inspector General David Sturtz leaked a surviving copy of the Shapiro murder memo to Fitrakis, who published it in July 1998.

Meanwhile, Miami International Airport made plans to demolish the hangar where Southern Air Transport was suspected of smuggling cocaine, a former U.S. Army depot that had been used by the CIA for more than 20 years. With Epstein acting as Wexner’s “logistics man” in Ohio, SAT relocated its world headquarters to Columbus to deliver products from factories in Hong Kong and southern China directly to Wexner’s network of Limited Brands’ stores.

The Ohio Department of Development and Rickenbacker Port Authority assembled a generous incentive package to lure SAT out of Miami, according to FOIA records obtained by Fitrakis.

The Rickenbacker Air National Guard Base was already a well-established military and intelligence hub when Wexner’s company planned to turn it into a consumer logistics port. The nearby Defense Logistics Agency, 15 miles away, was in charge of the global supply chain for weapons systems. A decade earlier, CIA technicians had quietly met Louisiana smuggler Barry Seal at the same base and installed hidden cameras inside his plane’s fuselage, before sending him back to Nicaragua on a DEA sting.

The state offered a $6 million low-interest loan and a half-million dollar development grant, while the Department of Transportation agreed to pay ten million dollars for infrastructure upgrades. The port authority freed up $30 million in revenue bonds to be used by the project, and the county made the facilities 100-percent tax exempt for fifteen years.

“While I was writing investigative articles for Columbus Alive…I found myself inundated with people leaking stories about corruption all over the city and state,” Fitrakis told Drop Site and TAC. Sturtz, the former inspector general who leaked the Shapiro murder file, spoke to the journalist specifically about Epstein.

“After that, he verbally gave me a lot of information about Wexner and Epstein’s ties to organized crime and the intelligence community,” Fitrakis said. “That’s how I learned about Southern Air Transport.”

Fitrakis contacted former Franklin County Sheriff Earl Smith to find out what he knew about Epstein. Smith’s office, he learned, had an ongoing investigation into drug smuggling at Rickenbacker, related to the CIA’s planes. “He knew Epstein was the point person in soliciting Southern Air Transport to come to Ohio,” Fitrakis said. Sturtz was dismissed from the Inspector General position in 1994, which he told Fitrakis he believed was connected to his inquiry into Wexner and Southern Air Transport. His successor also resigned after two months on the job.

In Columbus, the airline did not shed its drug smuggling pedigree. In 1996, customs agents discovered cocaine hidden aboard a SAT plane, according to a report in a Mobile, Alabama paper. SAT’s public information officer told the newspaper the plane was delivering “fresh flowers” from a large flower exporter in Colombia. SAT asserted it was “not tied to the CIA and would like to know itself where the cocaine came from.” By the time the Alabama incident hit newswires, the plane in question had been handed over to an insurance company due to “mercury contamination.”

The Columbus experiment ended one year later, as more of SAT’s sordid smuggling history was dragged into public view. In June 1998, after the airline had already collected millions of dollars in state subsidies, SAT decided to “park and sell off” its fleet of Lockheed Hercules planes. On October 1, 1998, SAT abruptly filed for bankruptcy—exactly one week before the CIA Inspector General released its official findings on Contra cocaine trafficking allegations.

“A Photo With Some African Warlords”

When Ghislaine Maxwell was interviewed by Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche in July, she was asked whether Epstein ever had any contact with intelligence agencies. Maxwell gave a vague response about Epstein’s business of “finding money” in Africa in the 1980s: “I think he may have suggested that there was some people who helped him,” Maxwell said. “He showed me a photograph that he had with some African warlords or something that he told me…That’s the only actual active memory I have of something nefarious — not nefarious… but covert, I suppose would be the word.”

In parallel to Iran–Contra, from 1984 to 1986, Southern Air Transport flew hundreds of trips inside Angola, with some runs connecting the capital city Luanda to Dobbins Air Force Base in Marietta, Georgia. Angola’s northeastern diamond-mining towns, cut off by unsafe roads and railways, were largely accessible only by air. SAT obtained a lucrative contract from Angola’s state-owned mining company to carry equipment to the mining towns, and carry diamonds out. While making trips to the mines, the SAT planes were suspected of air-dropping weapons to the rebel group UNITA with South Africa’s support.

South Africa profited handsomely from the Angolan civil war. Johannesburg became a booming re-export hub for illicit Angolan diamonds, as UNITA-controlled “blood diamonds” were under UN embargo and could not be exported legally from Angola. By the late 1990s, UNITA earned billions of dollars by smuggling diamonds to Johannesburg, where they re-exported with false certificates-of-origin and shipped onward to London and Belgium. A UN report estimated that over $1 million worth of diamonds were smuggled out of Angola per day in 2001.

Angola was the mirror image of Iran–Contra. As in Iran, Saudi money was the “bank” for Angola’s war. As in Nicaragua, trade in contraband (diamonds rather than drugs) was backed by an off-the-books arms trade. An associate of Saudi Arabia’s King Fahd testified before Congress that Saudi aid to UNITA was part of an informal deal with Washington in exchange for access to mobile radar surveillance systems. He recounted being told that tens of millions of dollars had been funneled through Morocco to train UNITA fighters, and claimed Prince Bandar had planned to sell oil to South Africa. The Saudi government has denied these claims.

In Columbus, SAT’s collapse was written off as the result of “financial troubles.” But before declaring bankruptcy in 1998, half of its fleet of Lockheed Hercules planes were sold to Transafrik, an Angolan airline based in the United Arab Emirates. SAT resumed its missions supporting diamond mining operations, as Angola’s civil war raged on. Decades later, Epstein bragged to journalists about making his fortune out of “arms, drugs, and diamonds.”

Epstein, for his part, only came to the attention of the international press after agreeing to ferry former President Bill Clinton around Africa in 2002 on his private jet, later dubbed the Lolita Express. Speaking to Hoffenberg in prison that year, journalist Vicky Ward asked why a man who had thrived in the shadows would risk so much with such a public spectacle. “He can’t help himself. He broke his own rule,” Hoffenberg said. “He always said he knew the only way he could get away with everything he did was to stay under the radar, but now he’s gone and blown it.”

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Epstein’s claim to have barely known Hoffenberg, and Wexner attempts to personally distance himself from Epstein, are undermined by the fact that both men knew Epstein’s cardinal rule—a rule he was apparently preternaturally unable to follow.

On June 30, 2008, the Florida state court accepted Epstein’s guilty plea to state charges of soliciting a minor for prostitution, part of a secret plea deal with federal prosecutors that allowed him to serve an 18-month jail sentence on a work-release program that allowed him to leave the jail and roam the world outside.

Four days before, Leslie Wexner sent his friend an email: “Abigail told me the result…all I can say is I feel sorry. You violated your own number 1 rule… Always be careful.” Epstein’s reply to Wexner was contrite: “no excuse.”