This article is taken from the October 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

The Ashes, that abrasive contest between the cricketers of England and Australia, is the oldest of sport’s rivalries, wandering all the way back to 1882. Yet it is skewed significantly in favour of the men wearing baggy green caps: Australia have won 152 matches, 40 more than England.

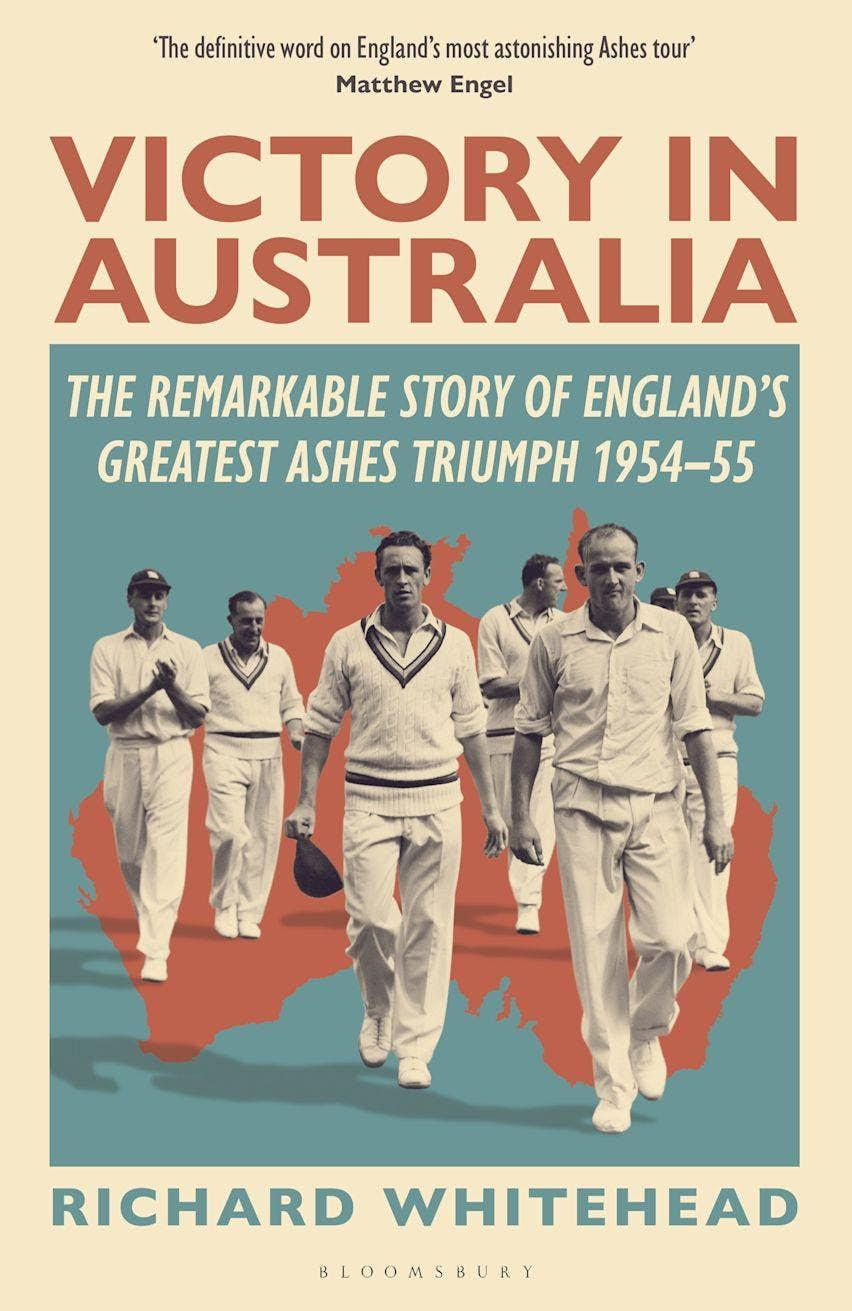

Richard Whitehead is not fibbing, therefore, when he calls this superb book about the 1954–55 series “the remarkable story of England’s greatest Ashes triumph”. England lost the first match in Brisbane by an innings and 154 runs, after Len Hutton opted to bowl. A chastened captain atoned for that blunder by leading his men to three successive victories before rain cut the final Test in half. England won 3-1, and on his return to Yorkshire Hutton was dubbed a knight of the realm.

As a 22-year-old he had made 364 against Australia at the Oval, then the highest score in Test cricket. It was 1938, and the opening batsman had the world to conquer. When cricket resumed seven years later he had lost two inches from his left arm, the result of a wartime accident in the army’s Physical Training Corps.

Other things had not changed. Australia remained dominant, beating England 3-0 in 1946/7 and 4-1 in 1950/1. So it was a personal triumph when the first professional to captain England — leadership had traditionally been the province of amateurs — guided England to victory in 1953 after they won the final Test at the Oval.

The players were not poor. Alec Bedser the opening bowler, Denis Compton the cavalier stroke-maker, and Godfrey Evans the flamboyant wicketkeeper, were supreme cricketers. To succeed in Australia, however, then as now, a captain needs fast bowlers who can stay fit in enervating heat.

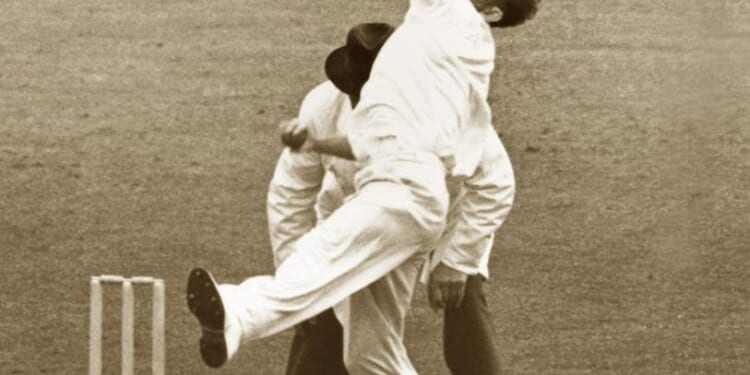

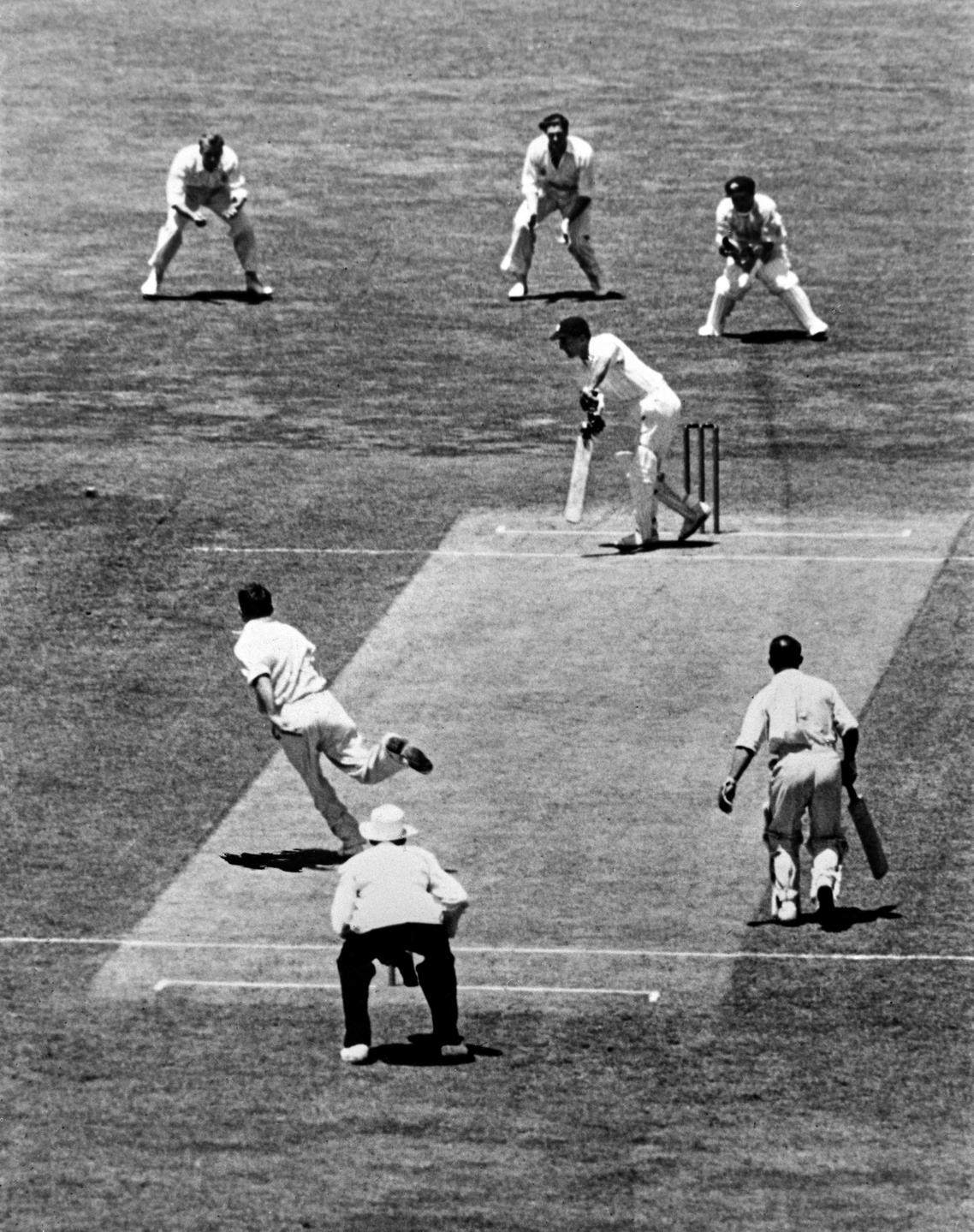

Having wished upon a star, Hutton was rewarded when Frank Tyson, a 24-year-old Lancastrian with a single Test to his name before the tour, exploded at Sydney. The Northamptonshire paceman took ten wickets, and England won a low-scoring match by 38 runs. Bedser, not fully fit after an attack of shingles, was dropped for that game, and played only one more Test.

Tyson blasted out another nine men at Melbourne, where England won by 128 runs. In the view of many Australians nobody had bowled that quickly since Harold Larwood propelled England to victory in the notorious “Bodyline” series of 1932/3.

Tyson proved to be a meteor, brilliant and brief. Back in England he made way for Fred Trueman, left out of the touring party for perceived bolshiness, who in time became the greatest of all English fast bowlers. Tyson, like Larwood, ended up living in Australia.

Hutton could also call upon another Lancastrian, Brian Statham, who supplemented Tyson’s 28 wickets with 18 of his own. Here were two men, young (24), fit and fast enough to knock over batsmen brought up on lively pitches. Three other young men also proved their worth: P.B.H. May, T.W. Graveney and M.C. Cowdrey (21 when the boat left Tilbury in September) all walked an inch taller when the party docked six months later. They were graceful batsmen responsible for England’s three centuries in the series, Cowdrey’s at Melbourne being particularly valuable.

What a different world it was. There were 28 matches in all, and Hutton had just two helpmates: Geoffrey Howard, the tour manager; and a bagman, George Duckworth. Away from the dressing room their main concern was keeping an eye on Compton, Evans and Bill Edrich, who often heard the chimes at midnight.

Hutton was an odd duck. Brought up in a Moravian community in Pudsey, he was a master of the crease. The Three Hs, they are called, the men who stand tallest in the parade of English batsmanship: Hutton, Sir Jack Hobbs and Wally Hammond. But his captaincy, and detached manner, inspired respect rather than love.

He was on his guard for good reason: despite his Olympian standing, he was almost unseated in the summer of 1954 by members of the MCC selection panel who preferred an amateur to captain England. How he confounded them. Since then England have won only four series in Australia, and one of those victories, in 1978/9, came against a team stripped bare by Kerry Packer’s alternative World Series Cricket. The finest of those triumphs, in 1970–71, was supervised by Raymond Illingworth, another son of Pudsey.

Whitehead, who tells this tale with a scholar’s eye and a dash of humour, has dedicated the book to John Woodcock, the Times correspondent who saw this story unfold. Perched on a celestial bough, the great writer must be proud.