This article is taken from the April 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

For 200 years Giorgio Vasari’s book Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects (published 1550) dominated how we thought about architecture. Vasari detailed the means by which Brunelleschi, Michelangelo and others not only conceived, but importantly drew and built imaginative work.

It wasn’t until the 1760s, when Johann Joachim Winckelmann published his deterministic idea of cultural progression — superior styles overcoming morally weaker ones — that authorship became a secondary determinant to architectural quality.

In his essay “No Style”, the architect Amin Taha suggests that authorship should have its day again. It is an argument deserving praise, not least because it has given Taha himself the intellectual strength to build unexpected, beguiling buildings. Sadly though, he is an exception, and we live in a time when authorship in architecture has sunk below even this secondary capacity.

I thought about Vasari’s concept of authorship when I was walking through the “Drawing Matter” collection, a unique holding of architectural sketches, etchings, lithographs, prints and blueprints dating back to the Renaissance that has recently moved to the edges of Soho from Somerset. Its owner and prime mover, Niall Hobhouse, together with a team of curators, host students from London’s best schools to discuss how great minds of the past explored the themes upon which they are working.

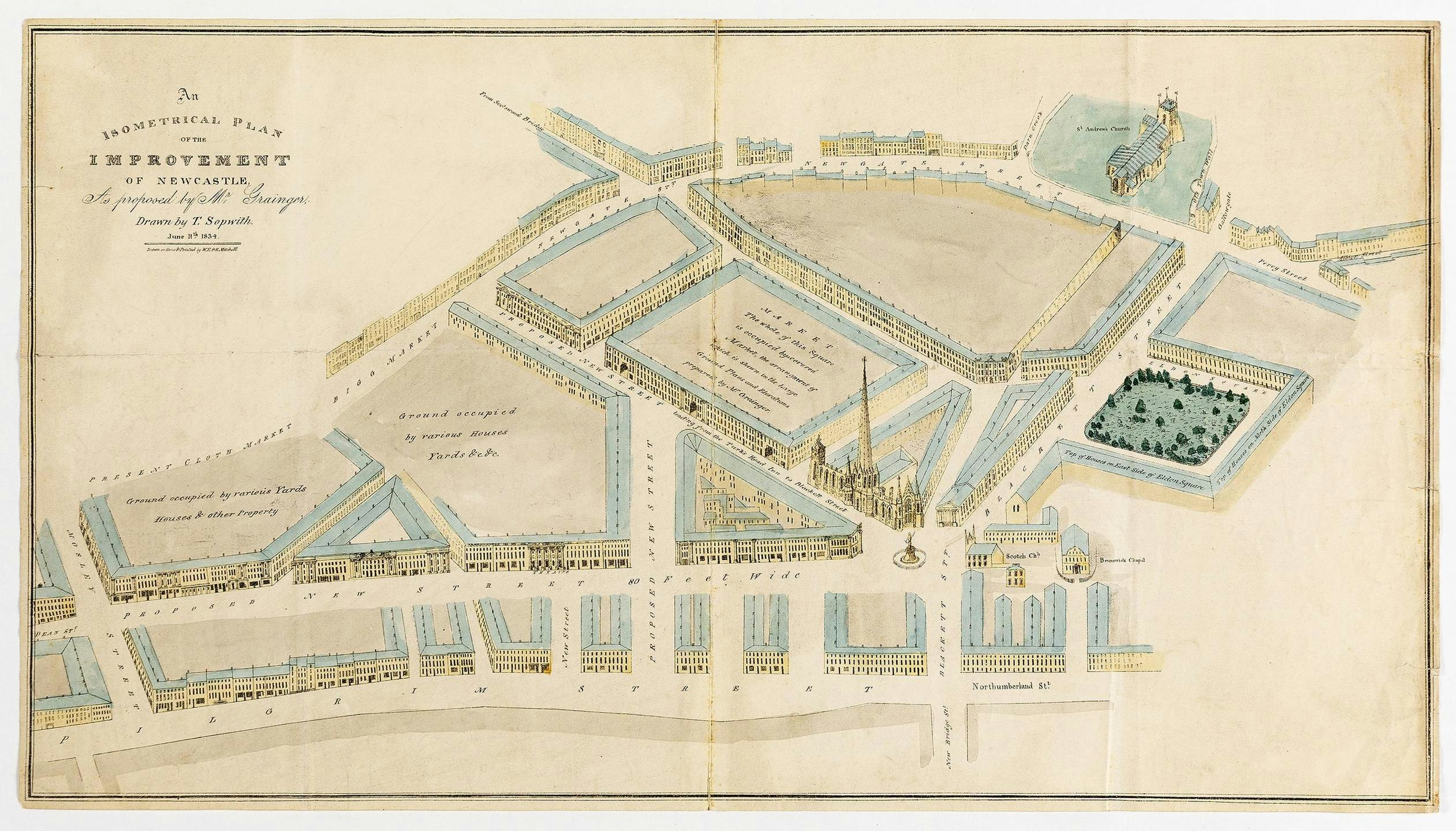

Key architectural figures drop in to seek inspiration. The avant-garde work of the 1960s and 1970s are popular but when I went there, it was to see drawings that conceive in a single hand large housing developments, some of which are shown on the pages adjacent. Drawings as intentions. Drawings as the first step in creating new places to live.

And how much these visions are needed. It is still early days, but it looks as if Labour is being true to virtually its only manifesto commitment by addressing the generational crisis in planning, particularly for housing. Councillors will be stripped of powers to block developments that comply with the local plan.

A wave of new towns appears to be progressing. Permissions for reservoirs and nuclear power may be forthcoming. There appears, however, to be stasis when it comes to imagining what these new places will look like, from architects but also from other participants as well.

There are plenty of pro-growth policy wonks out there who should be applauded for championing the cause of building in the face of huge opposition, sometimes, but not always, on the Right. However, the visual imagery that these bodies — Create Streets, Works in Progress, Centre for Policy Studies, Priced Out and others — make and share are not up to the task ahead.

Take Create Streets’s AI-generated work: shadowy impressions of a single mansion, with boulevards that usually feature a futurist tram system. Amongst the think tanks, there seems to be an odd consensus that sleek futurist tram systems are excellent, whereas housing must be odd computer-generated variations of mansion blocks built in West London between 1896 and 1910 — a strange commitment to tradition.

This attitude is founded on an erroneous assumption that we just need to jazz up the current industry and give it local codes so we build with nice stone or brick. Far more is at stake. Up to 12 new towns will be under construction by the next election. More than 1.5m new homes must be built within the next five years in the largest housebuilding programme since the war. Where does this stuff go? What powers it? Where’s the infrastructure? If growth is to create a new society, what does it look like?

Hopefully we are on the precipice of a huge change that will alter the British landscape, but these drawings are intentionally hiding this scale for fear, one assumes, of frightening the public. It is clear that we no longer want to address scale and size in drawings or even think about where the light rail line in the drawing goes. Any form of architectural expression seeking to succeed Modernism must address the volume and size that modernity demands. This should not be concealed.

In fact, one of the great joys of authorship is that it offers a means of creating a scalable aesthetic: how the bigger picture relates to the domestic. A brilliant example is Decimus Burton’s designs for a New Town in Fleetwood. The project failed largely because of a change in rail capacity, although Burton built a hotel, some houses and two lighthouses. The drawing, however, shows what Fleetwood could be and what in some way it still is.

Whilst the hand of the author may not be in the YMCA leisure centre on the shorefront, his intention is retained in the leafy avenues of Bold Street. The isometric of Richard Grainger’s plans for Newcastle show how a system can be worked across an existing street plan and an awkward topography. The scale and the single hand of authorship is the solution.

This is not a tirade against contemporary technology. Computers are tools of authorship; AI is not — though you can do fun, provocative things with it. Credit should be given to the Anglofuturists, an odd wonkland sect who use AI to its ludicrous limits, making images of Tudor wattle-and-daub space stations and Dubai-esque cities set within verdant countryside to show how futurity does not need to be dour or bland.

They understand that what might be done with the tool is to reorder what can be combined. Weirdly, though, when you use AI and patch in the Create Street prompts, you don’t get a St John’s Wood. Instead it looks as if someone gave Edward Hopper MS Paint to draw the Meatpacking District in New York.

If they were to employ someone to draw their proposals, including the schools, car parks and power stations these new towns need, I can’t help but think they would look very similar to the buildings that the architects they deride have built.

The work of Pitman Tozer, Haworth Tompkins and Lyndon Goode Architects in Fish Island, Hackney comes to mind: Brick-clad, concrete framed and contiguous with the existing warehouses. They are also within the limit of the ascribed eight-storey height that for some reason, some think-tankers believe is the level beyond which inhabitants start stabbing each other.

Drawings reveal hidden intentions as well as ambitions. The think-tank imagery is a product of the theory that architects hold the whip hand. “Architecture is, no question, designed by and designed for and decided on by people who have sophisticated tastes in architecture,” says online pro-growther Sam Bowman. This is bollocks. For prestige projects, a small per centage of professionals are invited to make challenging buildings. But the vast majority are subordinate to an industry run by developers and cost consultants keen to shift units.

Indeed, architects’ embrace of the environmentalist agenda can be seen as applying a brake to an industry they are not in control of. But even though the design profession has slid down the chain of command since the 1970s, it still has huge power in its ability to conceptualise. What we have now is architecture without architects.

Sadly, judging from their drawings, many architects seem pleased: pleased not to build anything at all. It may seem insane to those outside the profession, but the promotion of reuse has ripped through architecture schools and is embedded in certain corners of the profession — a product of the massive impact environmentalist groups had on the profession from 2016 onwards.

One example is particularly revealing. In 2017, the National Infrastructure Commission, the body designed to survey the UK’s key infrastructure needs and make recommendations to the government, set up an ideas competition for the Cambridge to Oxford Connection, an arc of land between the two university cities that takes in the rapidly expanding city of Milton Keynes. A corridor of growth has been mooted around a revised railway link; a place of business, opportunity and — despite fierce opposition — housing.

The winning proposal, VeloCity, promoted cycling along the 120-mile arc and prioritised preserving landscapes and “vistas”, before any vision of new settlement. The project is almost criminally sweet, with a faint whiff of Marie Antoinette about it: miniscule, insubstantial new developments aping model farms, tucked out of view behind existing manor buildings. Even worse was a proposal by 5th Studio which imagined linked waterways across reflooded fens, a National Park that would cover the watershed of the entire region: architecture as man-made flooding.

The terrific irony is that within this region lies Milton Keynes, the last heroic act of mass housing. One of the largest drawings in the “Drawing Matter” collection is an 18 by two-foot scroll, the product of a collective called The Grunt Group (Jeremy Dixon, Christopher Cross, Michael Gold and Edward Jones) who drew this suburb of Milton Keynes in its entirety: how it sits in the land, road connections, scale, typology ground plan for all 20 different housing types, the universal services system in axonometric. Using the technologies of the day, it replicates the Georgian terraces of London. It was built largely as it appears in the drawing, providing the cheapest housing in the city, though it has suffered disregard since and awaits investment to improve it. Drawing is the ultimate medium of growth, not a manifesto or a meeting.

Of course, this was a document for a developer, not an image to gain political traction. All drawings must seduce to a degree. Still they also convey intentions, they prompt other drawings and then more drawings, until one day you have a set in the hand of a site manager and he’s building stuff out from it. What the Netherfield Scroll shows is an ambition to produce scale in a coherent, resolved form.

Architects may be a less powerful group than they once were. Indeed the lack of architecture in architectural drawings speaks of a profession in an existential crisis. But their skills are desperately needed. If what they do needs developing or changing, then let that be the next step. If they are not built as designed, then in some way they have begun the process.

When we consider drawings outside the schools and design practices, it is often as utopian acts: the fine line etchings of Étienne-Louis Boullée, the crazed lithographs of Archigram — fanciful notions. However, drawing is also an act not merely of imagination, but of intention. It is a proposition and therefore a locale for discussion and debate. Just as we will have to build on fields, so the drawing inscribes ideas on a page.

It is no surprise that in the days of Vasari the great draughtsmen were also the great architects who were able to engage and beguile the viewer. Drawing is the push back against a historical determinism that says it shall not be so.