This week, BBC’s Newsnight brought together grooming gang survivors and a detective chief constable, ostensibly to discuss survivors’ experiences — a rare chance for police to demonstrate they’d finally confronted uncomfortable truths and learned from past failures. Instead, it became another platform for attacking Robert Jenrick’s claim that grooming gangs are “predominantly Pakistani” — dismissed as “misleading” by the officer who seemed more interested in scoring political points than engaging with the issue at hand.

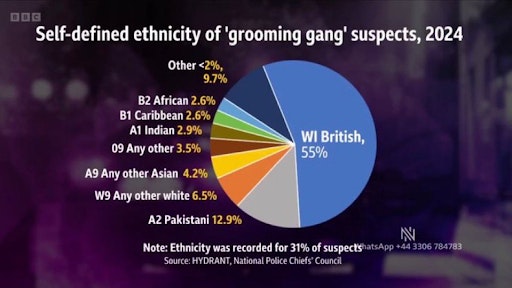

According to the graphic, 55 per cent of suspects identified themselves as “White British,” compared to 12.9 per cent identifying as Pakistani. Conclusive evidence, we are meant to believe, that Jenricks’ comments are misleading and incorrect.

Taking a closer look at their chart you will see the most important part of it is the disclaimer underneath that the ethnicity of suspects was only recorded for 31 per cent of the cases. Nearly seven out of ten suspects aren’t even represented in this supposedly definitive dataset. There’s no reason to think the missing 69 per cent are evenly spread out. Ethnicity recording could vary wildly, influenced by anything from language barriers to police hesitancy.

Given that the core controversy of the grooming gangs is the demonstrable, evidenced unwillingness of the police to properly investigate and prosecute these crimes, it’s difficult to believe that this 31 per cent of the perpetrators for whom data has been collected is accurate.

Even if you grant the goodwill to believe that the police are collecting this data accurately, it’s based on “self reported” ethnicity, given that the Ministry of Justice spends approximately £60 million per year on interpreters, it’s reasonable to question how suspects who claim to not speak English and rely on interpreters in courts could reliably self-report their ethnicity to police officers at the time of their arrest.

Another obvious problem is the data timeframe. The BBC snapshot appears to cover only 2024. Not only does the abuse happen over a timeframe of years, but grooming gang investigations and trials are a notoriously lengthy process with survivors frequently waiting years or even decades for their day in court. What information do we get about overall patterns of offending that spans decades by taking data from a single year?

The problems with this analysis don’t end there. “Grooming gangs” isn’t an official category of crime. The Conservatives introduced an amendment this year to create such a category, but the government swiftly blocked it. “Grooming gangs” therefore remains an informal term referring to group-based exploitation involving older men preying on vulnerable, often underage girls. Without official definitions, it’s unclear whether their dataset is lumping together all grooming-related offences like online predation or intra-familial abuse that effectively buries the specific group-based phenomenon that we see in places like Rotherham, Rochdale, and Oxford.

The BBC also neglected to mention that police-recorded crime data lost their “National Statistics” designation back in 2014. The UK’s own statistical watchdog explicitly stated that police records “do not meet the required standard for designation as accredited official statistics” due to inconsistent, unreliable recording practices.

As a data analyst, if I displayed a chart during a presentation and then immediately explained why it was misleading or unrepresentative, particularly by not accounting for sample reliability or overall population size, I would expect to rightly be asked why I hadn’t simply provided a clearer, more accurate chart. It’s unclear why Newsnight doesn’t owe national viewers the same transparency and responsibility.

The most egregious thing perhaps is that their skewed and flawed data doesn’t even disprove Pakistani overrepresentation. With Pakistanis making up around 2-3 per cent of the general population, the chart’s 12.9 per cent still points to a four- to six-fold overrepresentation in grooming gang offences — likely an underestimation given that trial transcripts show that often only a handful of men are prosecuted out of hundreds of perpetrators. It’s hard to see this as anything other than vindicating Jenricks’ characterisation.

This is institutional bad faith at its worst

To believe the BBC’s implied message, you’d need to assume the police arrest every single perpetrator, consistently record ethnicity across every single group, and get equal cooperation from every single suspect. None of these assumptions match reality, especially given the well-documented reluctance of authorities to pursue grooming cases.

This is institutional bad faith at its worst. Prioritising “community tensions” over public safety would be troubling enough, but doing it in front of survivors is unconscionable.The same priorities that allowed decades of systematic abuse to flourish unchallenged, now deployed once again before the very people who suffered the consequences. Years of inquiries, promises of reform and “lessons learned”, yet when confronted with uncomfortable realities, the instinct remains unchanged: deflect, deny, and double down.