This article is taken from the May 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

“You want to know what won it for Milei?” says the manager of an upmarket polo estancia an hour outside Buenos Aires. “Our kids voted for him. We told them not to be crazy — he didn’t have a party. We voted for the centre-right candidate, Bullrich, who came third. Then in the desempate [runoff], of course we voted for Milei rather than the Peronista, Massa. But he’s done a lot better than we expected. The kids were right.” “I don’t like Milei but he gives me hope,” adds another member of staff, who, like most Argentinians we met, clearly detests all other politicians more.

Having gained fame as a TV economist who only entered politics in 2021, Javier Milei became Argentina’s president with 14 million votes (56 per cent) in November 2023. However, he did so with a record lack of parliamentary support. He has only 38 La Libertad Avanza (LLA) deputies out of 247 in the lower house of parliament (85 including allies) and only seven (or 20 with allies) senators out of 73. Even if the LLA makes gains during mid-term elections in October it will still need alliances, notably with Mauricio Macri’s Juntos por el Cambio (JxC), to pass further reforms.

●

“This will be the second year in a row without a budget,” says a Buenos Aires political consultant. “But in Argentina if you don’t get the budget through, you revert to the previously agreed level of expenditure. In the absence of an agreed budget, public sector workers get a pay freeze. And any budget surplus is at the president’s discretion to reallocate, which he has said he will use to remove taxes.”

So, in Argentina’s inflationary economy, failure to get parliamentary approval for a new budget automatically results in real terms cost-cutting. Milei has already fired 30,000 public sector workers (10 per cent of the total), halved the number of government ministries and cracked down on expenditure on public works. All of this means public spending was reduced by a third in real terms in Milei’s first year, resulting in Argentina’s first fiscal surplus in 16 years.

●

Milei is not Argentina’s first libertarian of international fame. Its most reputable man of letters, Jorge Luis Borges, was a noted critic of Nazism, communism and then Peronism. “The Argentine, unlike the Americans of the North and almost all Europeans,” he wrote in 1948, “does not identify with the State. This is attributable to the circumstance that the governments in this country tend to be awful or to the general fact that the State is an inconceivable abstraction. One thing is certain: the Argentine is an individual, not a citizen.”

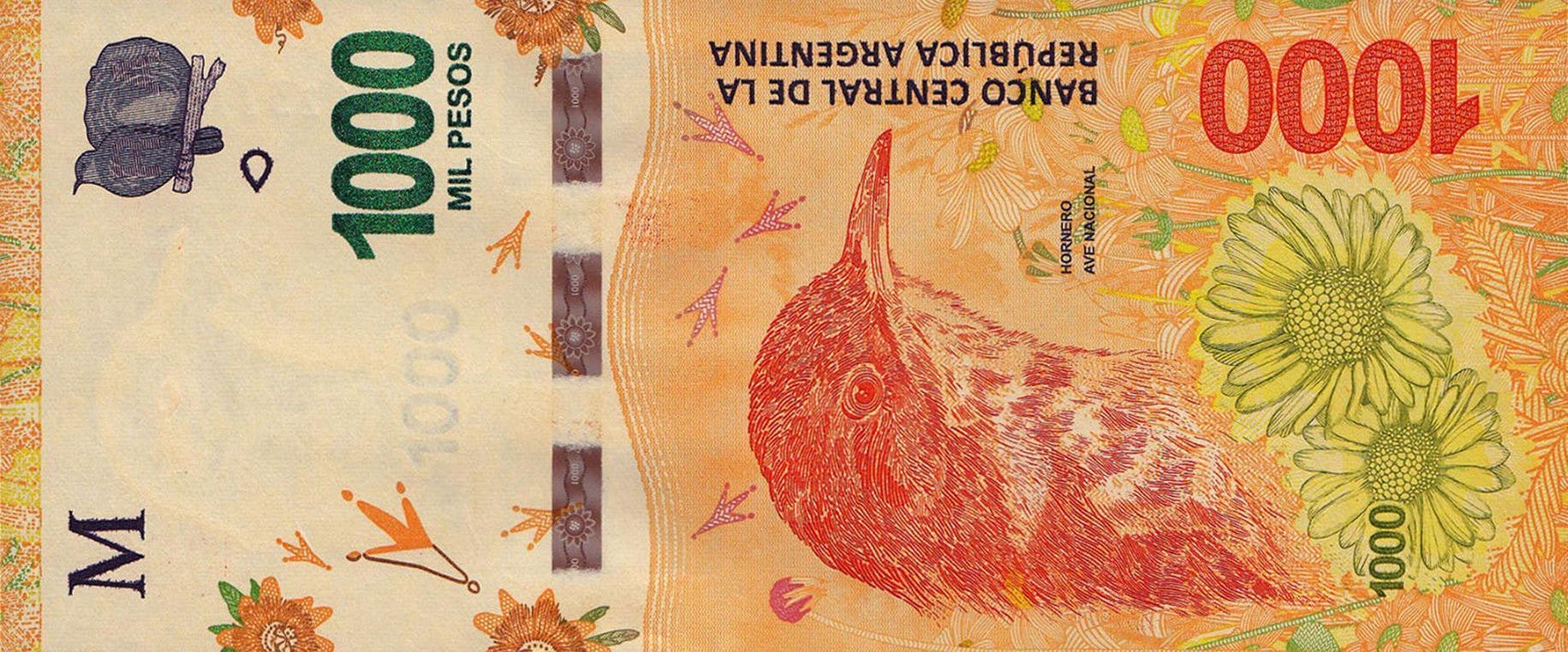

Perhaps because their leaders have been so universally awful, the 1,000 Argentinian peso note has a picture of the Hornero, the national bird on it, rather than any revered historic figure.

In 2001, Argentina broke its dollar currency peg and defaulted on $141bn of foreign debt in what remains the largest sovereign default in history. In the early 20th century, a third of Argentinians had been born abroad (the comparative figure for the USA was just 15 per cent). Millions of people left the poverty of Spain and Italy in the early 20th century, only decades later for their grandchildren to return to Europe disappointed.

Just before the default, the 1,000 peso note was worth about £800. Since then, Argentina has experienced two decades of inflation at an average of 35 per cent a year as permanent government deficits were funded by the central bank printing money.

Today, 1,000 pesos is worth about 77 pence. In other words, against the pound, not a particularly good store of value, the currency has lost 99 per cent of its value in 25 years.

Argentina is a cash economy with a deep distrust of its own money. It has stopped minting coins, and its biggest denomination note is 20,000 pesos (worth £15). Because there’s a big black-market economy, it can be necessary to carry a wedge of cash. Meanwhile, all hard assets and substantial transactions are priced in US dollars, which is why, it is said, no country outside America has more US dollars in circulation than Argentina.

Grupo Financiero Galicia is Argentina’s second largest bank behind state-owned Banco de la Nación yet, curiously, I discover that Galicia’s biggest fee earner is not asset management or insurance but the safety deposit box. “We have 77,000 in 20 different sizes, which can hold up to $100,000, for which we charge $2,000 a year,” says our man at Galicia. “There is a waiting list and even though $18bn came back in the recent tax amnesty [from the unofficial economy], no one dares give up their deposit box.”

●

Argentina was amongst the wealthiest countries in the world by the late 19th century, following an investment boom built on agriculture, railways, refrigeration and cheap immigrant labour. During the 1870s its economy grew 8 per cent per annum. In 1880, British capital investment in Argentina was just £20m, but by 1890 this had risen to £157m — accounting for half of British foreign investment at the time.

But in that year, following a failed agricultural crop and a political coup, Argentina defaulted on £48m of debt, its second (of nine) sovereign defaults, leading to a global financial crisis that required Barings Bank to be rescued by the Bank of England.

By the outbreak of the First World War, which coincided with the opening of the Panama Canal, Argentinian GDP per capita was 60 per cent of the US, 80 per cent of UK, 160 per cent of Italy, 210 per cent of Spain, 130 per cent of Chile and 600 per cent of Brazil. Until the 1930s, the phase “riche comme un Argentin” was used in France in the same way as “as rich as Croesus”.

Paul Samuelson recalled: “In 1945 I was a young talented economist. I was at the height of my abilities. If someone had asked me what part of the earth would develop the fastest in the next 39 years, I would have said: Latin America — Argentina or Chile. There is a moderate climate and a population with European roots … I was completely off the mark.” In 1950, the Argentinian economy was already underperforming its competitors, and it has continued to do so. Today, its GDP per capita is 30 per cent of the US, 50 per cent of the UK, Italy and Spain, 80 per cent of Chile and 120 per cent of Brazil.

The Argentinian fall from grace is unique. If you want to see the long-term consequences of an 80-year economic experiment in welfarism, protectionism, debt default, expropriation and corruption, all carried out in the name of the “people”, look to Argentina. “Before Milei,” our impressively erudite gaucho in Villa La Angostura suggests, “Argentina was simply a cautionary tale [for the rest of the world].”

●

Everyone in Argentina has a nickname, nearly always derogatory, often based on their looks. Our minibus driver tells me he is known as “Garlic Head”. Pre-emptively, I say that I am known as “Chuck” Norris, after the actor whose fame has travelled well. Nestor Kirchner, elected president in 2003, was known as “The Penguin”. He was succeeded by his wife, Cristina Fernández, who is currently appealing a six-year jail sentence for corruption but is still president of the Peronist movement. She has several nicknames, which translate loosely into English as “female dog”.

There followed the reformer Mauricio Macri who was known as “The Cat” and then, after suffering a loss of political nerve, a more derogatory feline term. Macri lost to Alberto Fernández who could have been called many things but became known as “The Wife Beater” owing to accusations, made by his partner, that have led to criminal charges. After all of this, you can see how ending up with Javier Milei as “The Madman” is — in historical context — not necessarily so strange or unflattering.

“Argentina has always had above-ground problems notwithstanding the quality of the underground,” says one of the top brass at Tenaris, amongst the country’s most successful corporations and a manufacturer of steel tubes for the oil and gas industry. “Traditionally the country has depended on an agricultural surplus, with 70 per cent of our crop being exported, making up two thirds of our exports. The black soil in the Pampas is so fertile it even doesn’t need fertiliser. But now we also have a positive energy balance. Now we have Vaca Muerta.”

Vaca Muerta (which translates as “dead cow”) in the state of Neoquen, northern Patagonia, is the largest shale oil and gas deposit outside North America, with the second largest shale gas and fourth largest shale oil reserve in the world. It has helped turn Argentina into a net energy exporter, creating a significant trade surplus and bringing in much-needed US dollars.

The area has been producing oil for 80 years, but fracking technology has seen a sea-change in production. Indeed, the area is perfect for fracking. “It’s a flat alpine desert, with lots of water from rivers that start in the Andes, and no one lives there,” says Vista, an independent oil producer with a long track record of success that is now focusing all its development in the area.

With only 10 per cent of the oilfield in development, its best years are still to come. Vista, YPF and the other Vaca Muerta drillers, which include global giants Shell, Chevron and Total, could already be producing much more, but for the lack of pipeline infrastructure to transport the oil to the Atlantic coast for export.

This is being addressed: the Oldeval pipeline is being extended to Puerto Rosales and a new $3bn pipeline, Vaca Muerta South, will connect to a deep water terminal at Punta Colorada and will add capacity of 700,000 barrels a day by the end of 2028. By then, it is estimated that Argentina will be exporting at least 1.5 million b/d and rank equivalent to Iran in the global oil market. This would bring in over $30bn (at $60 per barrel), resolving Argentina’s dollar solvency and currency convertibility issues.

Gas pipelines are also being built. However, the key for long-term monetisation — a pipeline to Brazil’s population centres — is still on the drawing board. For all that, Vaca Muerta can do for Argentina what the North Sea did for the UK in the 1980s.

●

“Wage negotiations used to be once a year, then twice a year, but, under the Fernández presidency, it became monthly, almost a perpetual negotiation,” says our man at Galicia Bank. “Living with 240 per cent annual inflation, you cannot imagine. Inflation is the prime driver of Milei’s popularity. The people said, ‘No más’ [No more].”

Inflation, which ran at 25 per cent per month when Milei became president in December 2023, has been brought down to 2.2 per cent a month. Exerting that level of price deflation is never painless, and the economy contracted by 1.7 per cent in 2024 in real terms (remarkably less than the previous year’s contraction of 1.9 per cent). But the economy is now rebounding: in the latest quarter for which we have data (Q3 2024), it grew 3.9 per cent whilst unemployment has fallen to 6.4 per cent, down from from 7.7 per cent when Milei became President. Argentina’s economy is now projected to grow five per cent for the next two years, with some economists projecting it to be 50 per cent bigger over the next decade.

●

Imports like cars and electronics are expensive in Argentina, but it’s possible to dine out well for a fraction of London’s prices. As we sit down for lunch at a famous Buenos Aires steakhouse, something on the menu catches my eye: Criadillas. At 12,000 pesos (£9), these testicles are more expensive than chorizo sausage at 7,000 pesos. But as every foodie knows, delicacy comes at a premium.

Mauricio the waiter, who tells me he is a resting actor, informs me the dish is lamb, as beef balls would be too big for a starter. Unable to pass up this opportunity, I order a plate to share. But when the testicles arrive, one of my fellow diners takes two, another one, so I am left with the residual four (two pairs, if you like). They look like brown drumsticks without the bone. I would love to say they taste like chicken, but they are spongy and, perhaps unsurprisingly, nutty.

In a hyperinflation economy with very high interest rates there is little demand for private sector borrowing and so, before Milei, commercial banks invested their customer deposits in local government bonds, where they are compensated by high nominal yields.

When government is a poor or even, as Argentinian history would suggest, a corrupt allocator of capital, then we must consider the lack of what economists call a “multiplier effect” of credit growth in the real economy. But when government starts paying for itself and doesn’t require external finance, this dynamic changes, bank deposits can instead be lent into the private sector, with the increase in credit having a positive impact on the real economy.

The private sector in Argentina has very little debt. For example, Galicia has three million customers, of which only 2,200 have mortgages. The Argentinian banks now expect 50 per cent loan growth in 2025, which would normally be worrying except when you consider that private sector debt is just 11 per cent of GDP and banks are deposit-rich with clean balance sheets. As our man at the bank says, “We have clients with no leverage and lots of new profitable lending opportunities.”

●

“I saw fund managers fall in love with Argentina under Macri and when things went wrong, they couldn’t get out,” says a wily veteran bond trader, now working for the Argentinian Central Bank. I ask what is different this time compared to the failure of Mauricio Macri (2015–2019). “Well, we have Vaca Muerto, and Milei is a force of personality, but also Macri fully liberalised exchange controls too early, so that when there was a problem, it turned into a stampede.”

Argentina currently fixes its currency to the US dollar with a one per cent monthly depreciation. Critics of Milei highlight the slow progress on currency liberalisation, which would allow foreign investors in Argentina and its own citizens to swap their pesos for dollars which, if done in an unlimited or uncontrolled manner, the country’s central bank would find itself unable to fund, catalysing another crisis.

“We think there is perhaps $15bn of foreign capital which wants to repatriate,” says the bond trader. “The central bank is working on a plan. This can be done in an orderly fashion giving priority to new flows rather than stock of historic profits. But we will be aggressive on fiscal but prudent on the capital controls. We would rather peel off the layers of the onion slowly.”

But critics argue that controls starve Argentina of foreign investment (since foreigners can’t take their profits out of the country) and leaves the peso overvalued compared with its major trading partner, Brazil.

This “overvaluation” comes with a trade surplus of $18bn, which is used to pay down maturing government debt — currently 88 per cent of GDP compared to the UK’s 97 per cent — the majority of which is in foreign currencies. So why fully liberalise exchange controls now when it can be done later with less risk given growing foreign currency exports from Vaca Muerta?

But, like the UK in the early 1980s, traditional exporting industries needing a weak currency (or, in Argentina’s case, hiding behind import tariffs) will become uncompetitive.

“With Argentina becoming a big net exporter of energy, we might have Dutch Elm disease with a petrodollar economy, leading to significant disruptive changes to employment,” cautions the bond trader. “We could also just bring inflation down by removing import tariffs, which would of course be what a free trade agreement with Trump would involve, but these would make large portions of the economy uncompetitive overnight.”

Bucking the general fate of incumbents taking difficult decisions, Milei’s popularity has increased from 50 per cent when he was elected to 54 per cent today. He banned the protest groups that led to almost daily shutdowns of downtown Buenos Aires, cleaned up the streets and empowered the police. It is, in Milei’s view, a moral as well as an economic revival.

Nevertheless, Argentinian politics, which had previously been Balkanised into factions, is now largely Milei versus Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, the old Peronist lizard, who is currently seeking immunity from her jail sentence by virtue of being top of the Peronist deputy list for October’s mid-term elections. Smaller parties are likely to suffer most from the coming abolition of the “PASO” primary system, and it is tempting to foresee that the more Argentina becomes a two-party system, the more that is likely to suit Milei.

After almost a century of decline, scepticism and corruption, I found Argentina full of fragile hope, personified in trust in “El Loco” Javier Milei. Are we at the start of another boom-and-bust cycle, or something more enduring? Much will depend on Milei. But to paraphrase Walt Disney, you don’t have to be crazy to run Argentina, but it seemingly helps.