This article is taken from the November 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

Before this summer, I hadn’t been to Poundbury apart from a fleeting visit in the mid-1990s. Back then, it was not much more than a new housing estate in open countryside halfway between Dorchester and Maiden Castle.

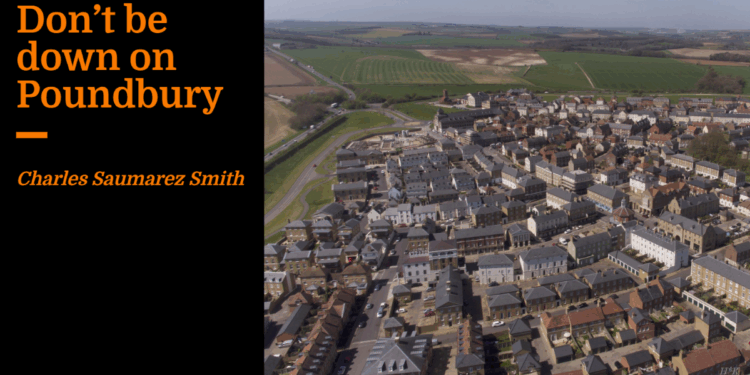

So, I was totally ill-prepared for the shock of arriving recently to find my way through a small- to medium-sized country town on the scale of Broadway or Moreton-in-the-Marsh, except ultra-quiet, all of it built in the last 30 years, and without any tourists. It has a policy of no sign-posting.

Most of the criticism of Poundbury, and there is a huge amount of incredibly rude commentary (Stephen Bayley describes it as “fake, heartless, authoritarian and grimly cute”), comes from people who only saw Phase 1 of the project when it was all brand new and felt, not surprisingly, a bit raw and experimental.

After all, it was a manifesto: against so many new-build, suburban housing developments which have no character, no infrastructure and are not built to last, as well as against the social experiments of so much modernist housing development which was often also poorly built and even more poorly maintained.

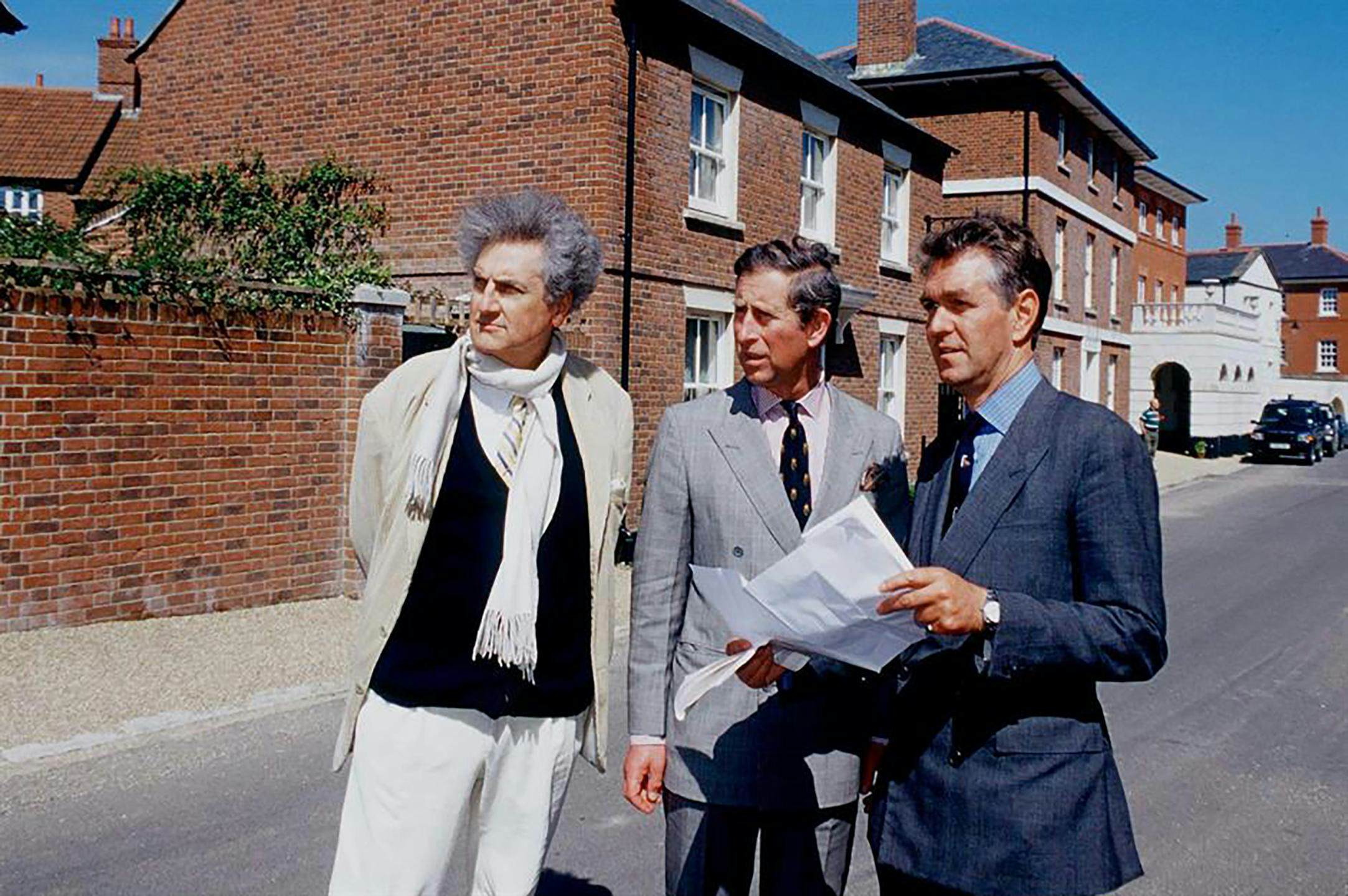

It was an attempt to demonstrate on the part of the then Prince of Wales and his late consigliere, Léon Krier, that there are perfectly legitimate building types which have worked well in the past and could, and should, be used again.

It is what architects stigmatise as “fake” and “pastiche”, but if it is well-built, has character and is affordable, then it turns out that there are lots of people, indeed, now over 4,000, who are only too happy to buy into a project which is much more spacious, more green and better built than any other suburban development that I have ever seen.

The problem was that it was a project of the Prince of Wales and so was assumed to be a plaything, a piece of Marie Antoinette-style fakery, in spite of the fact that he had a well-established interest in ecology and community architecture before he was interested in classicism. For the Prince of Wales, it was a social project as much as an architectural one.

Is it possible to reduce dependency on the motor car? The answer unfortunately seems to be no. Although the idea was to make the scale of the project walkable and all the urban amenities are within easy reach, people outside London are still wedded to large cars. Although many of the houses have garages, they use the garages for storage and park their people carriers outside their houses.

The central square has a branch of Waitrose, so the main square is a car park. I didn’t see a single bicyclist, nor, oddly, are there bicycle lanes.

Is it possible to mix social housing in with houses on the open market? The answer to this is, yes. One of the admirable things about Poundbury is that it has a high per centage of social housing, although this is nowhere evident. This part of the project is a success, although there is a feeling in the social surveys that the community is just as class stratified as everywhere else.

Is it possible to create an urban environment which its users embrace? Again, from the feel on the ground and chatting to a few residents, the answer seems to be yes, and it is this which the critics should pay attention to.

It’s spacious, well laid out, and with a great deal of variety in the streetscape. There are plenty of cafés dotted about. There is remarkable variety in the styles of architecture used, from flint-fronted rustic cottages to a late 19th century bit of Hampstead Garden Suburb.

Stage 1, completed in 2003, looks and feels like a Cotswold village. The street plan is dense and there is a cottagey feel to it. Stage 2 was more European, more experimental, with lots of different architects trying different ways of creating a town.

I was told that there had been problems with so many architects being involved and the quality of some of the building was not as high; but this is the biggest part of the project so far, it is quite diverse in character, and I enjoyed exploring its back streets.

Much of Stage 3, the most recent, looks like a version of Cheltenham, with good streets of straightforward, late 18th- and early 19th-century housing types, done with confidence, all of it looking unexpectedly established, even including a house on the edge of the town which the owners had moved into just last week.

They were only too pleased to have moved to Poundbury from Birmingham. So would I be. It looked infinitely preferable to most new-build housing estates, including, for example, the vast new housing estates constructed outside Cambridge. If people like living in it and are happy there, why does it attract such odium?

The answer would appear to be that most architects are trained to loathe everyday, middle-class aspirations — the dream of a comfortable retirement in which it is possible to walk the dog straight out into beautiful Dorset countryside.

Wanting this dream is stigmatised as a fake ruralist fantasy and providing an opportunity to fulfil it a product of royalist make-believe. The government has promised to build new communities. Where else are there good models of recent new towns?